Issue 2/2007 - Net section

Roaming Around

Digital divide, »1-dollar-a-day« economies and the question of access

The networked world is at one and the same time a fragmented world. The digital divide refers to the social, economic, technological and geographic gap in access to data transfer. The rifts run right through the heart of industrialised nations, but above all between North and South. In addition, the regional code for DVDs separates Europe from Africa. The Copyleft movements organised around Open Source and Creative Commons are now taking a critical look at the primarily Eurocentric thrust of questions posed. The cross-continent Copy/South-Dossier (http://www.copysouth.org) documents this.

»How many websites about Africa will we create? What do we have to communicate about ourselves? What can we teach the rest of the world? That is more important than technology as such«, comments Nigerian filmmaker Ola Balogun in the documentary »Afro@Digital« and describes a continent of dramatic differences: »There are really two Africas, side by side: here we find the class of the elite, who travel abroad, have access to modern things, virtually round-the-clock electricity, telephones at home and Internet access, and watch digital satellite television. And there we find Africa in remote areas, in villages and also on the outskirts of towns, with no electricity or running water, no likelihood of having a phone in the near future, people who watch television occasionally without being integrated into the newest technologies. They merely hear everything as distant rumours.«

[b]Threshold[/b]

It’s often said that there are more phone lines in Manhattan than in sub-Saharan Africa. But is this still the case in the age of mobile telephony and the spread of digitalisation? The storming of Ceuta, the Spanish enclave in Morocco, was coordinated by refugees from the South via mobile phone. Mobile phones directed them along the route towards Europe as instruments of migration and were promptly confiscated by the local police. Who then is actually the gatekeeper of the digital divide, deciding between the »digital haves« and »have-nots«? Rupert Scheule notes in the initial discussion on the book »Vernetzt gespalten«, »is not our digital divide discourse part of the exiling option it criticises«?

The image of division, which plays into the hands of widespread Afro-pessimism, can be counteracted by pointing out the rapid spread of connectedness in the global South (mobile telephones, Internet cafés, WiFi, WiMax), particularly when compared to terrestrial structures, which mainly date back to the colonial era (telephone, water, electricity, road, rail). In India, an emerging economy, British firm Vodafone International Holdings B.V. purchased two thirds of the Hutchison Essar Ltd, based in India and Hong Kong, for the equivalent of 8.5 billion Euro, in the process becoming one of the largest providers on the sub-continent. No other market, with the exception of China, is growing at such a rapid pace, with 6.5 million new mobile phone users every month. So far only 13 per cent of the population owns a mobile telephone, but the government estimates that as early as 2010 there will be around 500 million mobile phone owners.

[b]Mobile telephones instead of land lines[/b]

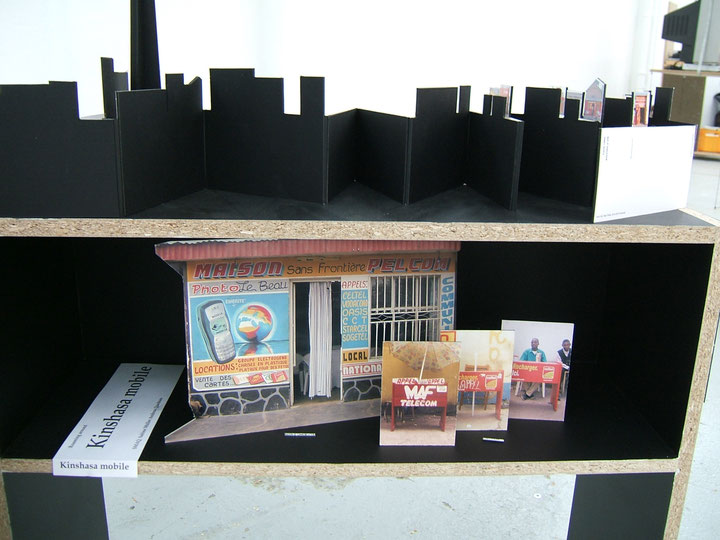

In Africa’s third-largest city, Kinshasa, the national telephone company operates only 10,000 land lines, and as a consequence over 8 million inhabitants outside the former colonial centre do not have land line connections, The introduction of prepaid telephone cards significantly speeded up the telephony boom. This simple payment methods offers the prospect of profits in the South too and at the same time echoes the practice of selling everyday commodities in the streets, available in one-day portions. Even tins of tomato puree are sawn into three parts and rice is re-packed into small bags, as people can often afford one single portion. Thanks to prepaid cards for a few minutes of conversation virtually everyone can afford to make a phone call. Access to telecommunication is not a public good here, but is embedded in African-style flexible capitalism.

In 2005 the minimum number of minutes per card was reduced from 20 minutes to one minute. In the poverty zones of »one-dollar-a-day« economies, this type of telephone card guarantees direct cash flow, as the pre-paid principle, introduced ten years ago, does not call for complicated accounting, contracts, address management, accounts or subscriptions. Telephone companies thus outsource sales to card vendors in the city, who in turn can secure an income for themselves. The Maisons de communication offer calls on mobile phones leased for a short period, sell prepaid cards or give users a chance to top up their credit. Shop owners tap into the flow of customers, selling or repairing telephones, offering photo services or working as hairdressers, or even running chair rental business, or indeed selling cosmetics, medicines and groceries. These establishments came into being as their owners were prepared to shoulder the entrepreneurial risk, with telephone companies only becoming involved subsequently. Whilst Vodafone donated paint for the buildings in a move to build corporate identity, Celtel handed out fixed sales tables, which shop owners often inscribe with their own individual texts. Celtel also gave vendors brightly coloured overalls, so that they stand out on the bustling streets.

»Technological simplicity« – as Sabine Müller and Andreas Quednau put it in their field research on Kinshasa – underpins this expansion: rather than relying on land lines, electricity supplies or asphalted roads, the key factor is customer flows. An antenna costs 50,000 dollars, takes up very little space (small footprint), and is linked to other masks via microwave, with a growing tendency to switch from diesel to service-friendly wind and solar energy. In the course of her study, also funded by Jan van Eyck, Tina Clausmeyer discovered that mobile telephones offered diamond miners and intermediaries a global overview of the market for the first time. They call their compatriots in Kinshasa – focal point for certification and shipment – or ring Antwerp direct: almost 80 per cent of the rough diamonds mined in Congo are polished there. And so find out how their work increases the stones’ value. Since then, some miners have launched attempts to at least avoid intermediaries.

[b]my iLife[/b]

Access to knowledge and culture, which are increasingly assuming digital forms, seems to be of existential importance. Everyday life in the North is increasingly embedded in digital technology, whether one thinks of appointment calendars, address books, or of how we consume music and videos, or even just read a newspaper. Apple coined the brand name iLife for this phenomenon. Millions of »100 dollar laptops« with Open Source software are now ready for shipping to give children and young people in the global South free access to the world wide web too. The project from the research hotbed around MIT aims to enable participation in the globalised world. »We know that many people in Africa are not able to use the Internet … That’s why I’m thinking of introducing ›mediators‹, which could create new jobs in Africa. They will be 21st-century ›village teachers‹ – people on the spot with computer training«, explains Mactar Sylla, director of broadcasting in Senegal, outlining his vision for the future in »Afro@digital«.

Voices are being heard particularly to the north of the digital divide asserting that providing food and clean water is more important. Quite apart from the fact that it is not a question of either laptops or drinking water, but rather of computer plus the option of using it to tap into new sources, there is an undercurrent of superiority to these questions about what people in slums from Libya to Brazil are supposed to do with a laptop. Field trials have demonstrated however that young users are perfectly capable of using the devices, which are powered manually via a handle, in ways not envisaged by the instruction manual, using the screens to provide light in their huts if they have no electricity. There’s no way of predicting what will happen when millions of kids linked via wireless connections can convey their view of the world – or input data for firms as outsourced cheap labour.

[b]Afro@Digital[/b]

»Why are we talking about new technologies on a continent where people go to sleep and wake up with the terrorism of poverty? « Those are the opening words in the video reportage »Afro@Digital« by filmmaker Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda, born in what was then Belgian Congo – a country in which the raw material for nuclear bombs is now extracted, along with the mineral used in mobile phones, DVD players or games consoles. »The price of coltan went up as the digital revolution unfolded; that contributed to the war in the Congo.« The director visited a plethora of filmmakers, musicians, programme directors and engineers active in the new Africa.

»People used to communicate by post … Letters were delivered in 15 to 20 days, replies took their time … My clients all over the world can get in touch with me quickly on my mobile phone. You can get through to Europe in two minutes. Direct.« An Islamic cleric from Burkina Faso describes the changes in these terms. »The first phone call in Africa, around 1986 or 1987, was made through the Telecel network in Kinshasa – Telecel Zaïre, as it was in those days«, to quote Alexandre Kande Mupompa, Telecel Director for Burkina Faso, commenting on how it all began. »There’s a long waiting list for a land line in our country. GSM technology provides a rapid response. And contributes to revolutionising our lives. People can register and get connected quickly. GSM can connect up anywhere and radically alters everyday life.«

Mactar Sylla, perspicacious director of TV and Radio Senegal, talks about mobiles when he thinks of the television of the future. However »telecommunications in Africa are not reliable and are relatively expensive. If you drive out and take a looks nowadays, people can communicate with their compatriots, children, relatives abroad. That brings people much closer together.« Digital life saves time and money: »We have serious problems with basic infrastructure, with travel, communication … However with the Internet, video conferences and other digital technologies you can actually communicate on an equal footing at the same time. That means overheads are reduced: as the director of a firm with nine regional radio stations and 15 national broadcasters, I can contact all my staff via Internet, drastically cutting communication costs.«

[b]»Nollywood«[/b]

Something that is still just a dream for the film industry in the North has long become a reality in West Africa: from its base in Lagos the »Nollywood« film industry, which does all its production and distribution digitally – with pioneering recording using DigiCams and mass distribution on DVDs or VCDs as well as in beamer cinemas – provides a steady supply of films to the densely populated coastal region of West Africa plus the diaspora abroad. Nigeria’s film industry is the third largest production region in the world – after »Bollywood« and »Hollywood« – and is distributed on the same markets as so-called pirate copies of music, films or software that circumvent the global copyright regime.

»Nollywood« plays a groundbreaking role in the digital revolution shaping the world of cinema. The young African filmmakers Alain Gomis and Newton Aduaka rave about how liberating (from costs too) digital video technology is, whilst Charles Mensa, Director of the National Cinematographic Centre in Gabon, talks of how much time this saves compared with chemical film-processing: »It’s marvellous not to have to wait for 72 hours any longer to get the rushes in the lab and find out if there was a problem.«

»We can have more cameras and more imagination«, as Georges Kamanayo describes the hope of no longer being dependent on financiers from the North or state institutions in the South. As Mactar Sylla sums up, »We have a problem with the industry, but here too Africa has a few cards up its sleeve, for we have original things to narrate. Digital allows us to participate on a fair basis, for it offers many different facets. « There is now space for a dozen digital channels in the slot once occupied by one analogue channel. »Some believe this is a curse for Africa, for the continent produces too little. But it could be seen as an opportunity too, for everybody it could mean everyone having to deal with all kinds of approaches and issues. Africa must address its own concerns and present an African vision of progress to the world.«

Translated by Helen Ferguson

Agency/Tina Clausmeyer/Wim Cuyvers/Dirk Pauwels/SMAQ (Sabine Müller/Andreas Quednau)/Kristien Van den Brande, BRAKIN. Brazzaville – Kinshasa. Visualizing the Visible, Basel/Maastricht 2006; cf. the discussion in the Lektüre section of this edition.

Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda, Afro@Digital, Congo/France 2003, http://www.newsreel.org

Rupert M. Scheule/Rafael Capurro/Thomas Hausmanninger (eds.), Vernetzt gespalten. Der Digital Divide in ethischer Perspektive, Munich 2004.