Issue 4/2008 - My Religion

The prophet’s perspective

The »Order of the Persecuted« by Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

[b]»He was black. God’s missionary. He showed people the path of salvation. And so they called him Jesus. Accompanied by his elder brother. He headed to the north-east of his country. There He found a race that was hard to convert. To convince that race by the power given to him by God. He became an entirely white man in the presence of an enormous crowd. That act proved fatal: for He was not supposed to do this in public. Having thus lost the origin of his colour, He died enslaved to his passion after having been disowned by his race. Verily I say unto you, God’s envoys have two enemies: man’s lack of faith and the imprudence of the human body in which these envoys must fulfil their difficult mission.«[/b]

Cheik Nadro, Book of Divine Laws, Section 199, 23rd June 1948

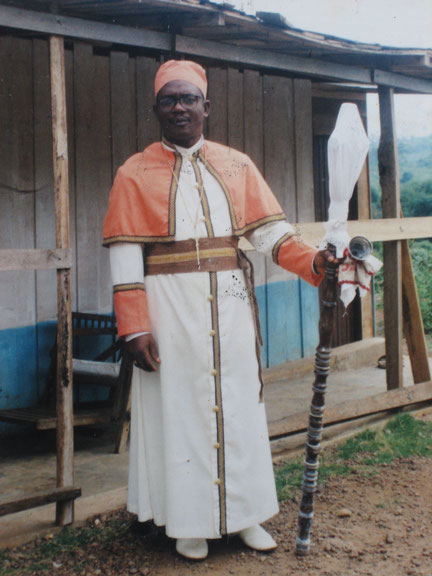

In March 1948 Frédéric Bruly Bouabré announced in Dakar that he had witnessed a divine revelation. Since then, he has viewed himself as a prophet: »When the heavens opened up before my eyes and seven coloured suns formed a circle of beauty around their mother sun, I became Cheik Nadro – he who does not forget.«1 Subsequently he apparently received a celestial command to set up his own religion – the Order of the Persecuted. Critics often write that the drawings produced by this artist, who is held in high esteem nowadays, are rooted in these events. However Bruly’s works do not stem from this episode.2 The history of how they actually came into being is much more complex. His first works, which date from the 1970s, were illustrations for stories and proverbs. Later Bruly developed this line of work systematically in order to »escape from poverty«. The advantage of this confusion is that it responds to the desire for authenticity and retrospectively renders his oeuvre more coherent. However, over and above his rhetorical skills, one might attempt to find a reason for this shorthand version that distorts the facts by radically simplifying a career path that is infinitely richer than it appears at first sight. If we attempt to grasp this richness, we must for a moment shift our attention from the artist for a moment and concentrate on the prophet. It is not about playing one off against the other, but rather about drawing out a fundamental aspect of Bruly’s career which demonstrates the relationship that links his oeuvre and his approach with the history of his country – a history studded with prophetic movements in which there is little room for the myth of the elder endowed with ancestral wisdom that is so frequently associated with Bruly.

The history of the Côte d’Ivoire since the 1920s is choc-a-bloc with prophetic figures, a real prophetic tradition comprising links, filiations and identifications.3 This tradition ascribes a privileged status to quasi-Weberian charismatic personalities, some identifying themselves with »black Christ figures« at the head of syncretic movements whose avowed intent is to make Ivorians – or rather, Africans in general - the equals of whites or indeed to enable them to compete with white people. The actions of these religious figures are rooted in the struggle against »fetishism« and »sorcery« in the name of one single God. Their discourse draws on religious and political repertoires combining Afrocentrism and healing practices, nationalist ideologies and millennial messages of salvation.

The dynamism of the prophetic scene had reached its climax when Bruly, returning from Dakar in 1958, attempted to set up his own religion in Zépréguhé, his home village in the central western region of the Côte d’Ivoire.4 Some movements that developed in the 1930s to 1940s institutionalised their undertaking as churches, whilst others, younger and more opportunistic, organised themselves as healing villages. The increasing number of options on offer, and thus the growing competition, combined with a versatile target audience, undermined poorly structured movements. In this context, where it became a proof of strength if a movement continued to survive, there was no scope for Bruly to make concessions regarding the stability of his movement. His religion, perhaps constrained by excessively rigid ritual provisions, never became part of the prophetic landscape in the Côte d’Ivoire. However without this phase of realised socialisation, it is difficult to define both his intentions (perhaps therapeutic?) and the »liturgy« associated with Bruly’s role as a prophet. There are almost no tangible traces of the passage of Cheik Nadro, with the exception of the »Book of Divine Laws«. This manuscript brings together the instructions that God conveyed to the prophet. He set store by transcribing them every day in the form of short paragraphs, each with a precise date affixed. The rhythm of the revelations slowed after 1951 and drew to a standstill in 1963.

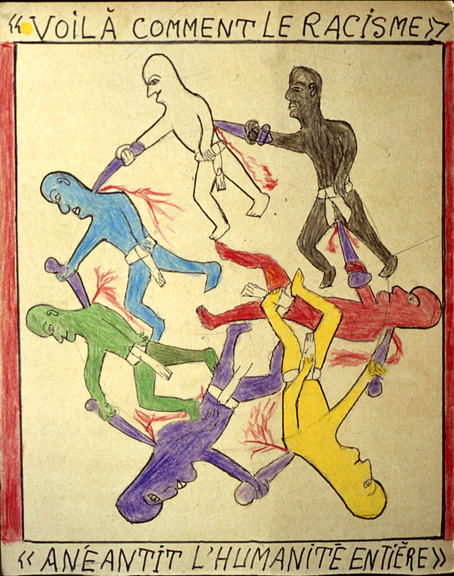

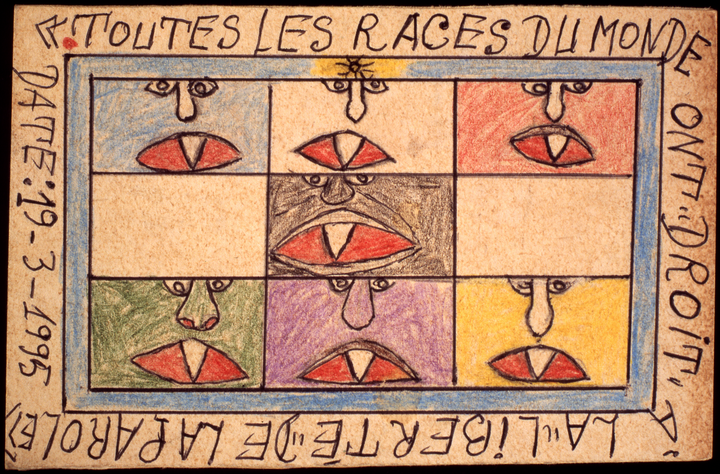

However, reading the »Book of Divine Laws« gives us an opportunity to gain a clear picture of Bruly’s embryonic prophetic role. He preaches ecumenism and tolerance towards the religions of the Book, but also towards so-called traditional religions, which marks a clear break with the rigid attitude of most Ivorian prophets. Like the bulk of independent churches and prophets in Africa, he takes the Old Testament as his preferred role model – whence the schemata of oppression/salvation adopted to describe the ethics of the Order of the Persecuted. Bruly thus asserts that the victims of oppression are superior to those who oppress them. To be more precise, he asserts that: »There are two communities in the world. There is a good community and an evil one. Mostly a black community numbers among the good communities.« The Order of the Persecuted directs its attention primarily to this community. Bruly’s order thus fits neatly into the widespread analogy, adopted by many Afrocentric movements in Africa and America, which model their appraisal of the history of the black race on the persecution of the Jews, some going so far as to claim that the Africans were the original Jewish race. In the thinking of Bruly – and others – »persecuted« Africans are seen as the chosen people.

The Afrocentrism characteristic of Bruly’s thought is expressed clearly in many of his drawings, particularly in those where Bruly states more or less explicitly that the most ancient civilisations came into being in Africa, that Africa’s influence shaped the rest of the world or indeed also when he depicts our ancestral parents, Adam and Eve, as black. This topic also appears in some stories, such as for example »Domin et Zézé«, though here it should be noted that the subtitle he gave to the original manuscript (1964) »The order of appearance of human races on Earth« was not included when the book was published in 1994.5 Nevertheless, the manifest Afrocentrism in Bruly’s writings does not conflict with his humanism. As soon as the teleology of the situation has been, in his opinion, re-established, the prophet and the artist alike can express peaceful notions of universal familial ties. This notion is presented much too frequently outside any genuinely historical or biographical context. It is therefore perceived as being thoroughly naïve. As a consequence Bruly’s oeuvre tends to be valued not so much for its complexity, or indeed its inner contradictions, but instead for its simplicity, something that has more or less been invented by the critics.

Whilst Bruly never betrayed his relationship to God, his career as a prophet gradually dwindled away. As we have seen, he stopped systematically transcribed his revelations in 1963. The Book of Laws nevertheless took on new life in the prophet’s drawings. Bruly set great store by representing the most emblematic of the revelations given to him, and new ones saw the light of day as he drew, although they were never shown in public in those days.6 Bruly himself was of the opinion that his prophethood only appeared to have failed, for he now affirms that his religion was never based on proselytism and the desire to bring together a group of the faithful. However, one cannot but note that for some years now Bruly has been assuming the air of a prophet without any misgivings whatsoever, which was previously not the case. Released from material worries thanks to the success of his drawings, he appears to have assumed full responsibility for his mission. The Order of the Persecuted is certainly still a theoretical religion, but the drawings have opened up another terrain for a revelation Bruly asserts is his very own, claiming: »I was the first one to reveal the idea that God writes, that God is a writer. I am referring to divine writing.« According to Bruly, divine writing, which he also calls »the writing of the dead«, collecting, transcribing and interpreting its signs, is embedded in a system of correspondences with human writing. The world becomes a book, in which God writes constantly – through animate beings, objects, phenomena and traces.

Through his drawings and the world underpinning them, interpreted entirely in graphic terms, Bruly thus aims to prove God’s existence. In this enterprise the world of art is his most important ally – as Bruly realised very rapidly. It is left up to us to recognise this fact and ask ourselves whether, contrary to what has often been claimed, it is not actually his artistic career that gave impetus to his role as a prophet rather than vice-versa.

I wish to thank Dominique Malaquais for her careful reading.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 The comments from Bruly Bouabré come from interviews conducted between May and July 2002 in Abidjan.

2 Although no trace has been found, we cannot exclude the possibility that Bouabré – like other African prophets – recorded his visions in writing.

3 For a complete overview of prophetic religions in the Côte d’Ivoire c.f. Jean-Pierre Dozon, La Cause des Prophètes. Politique et Religion en Afrique Contemporaine. Paris 1995.

4 A description of the inaugural ceremony for the religion of Bruly Bouabré/Cheik Nadro can be found in: Denise Paulme, »Naissance d’un culte africain« in the Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines, 149, 1998, pp. 5–16.

5 Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, La Légende de Domin et Zézé. Paris 1994. In the same register, Bruly explains that whites are really the offspring of black albinos. As they could no longer stand Africa’s climate, they migrated towards more clement climes. If one follows this idea right through to its logical conclusion, this theory, popular in Afrocentric circles, would identify environmental determinism as the origin of the profound dichotomy between black and white. Bouabré prefers to conclude that this notion of a single origin signifies universal affiliation amongst humankind.

6 The drawings were shown for the first time in 1989 as part of the exhibition »Magiciens de la terre«. Before this, the very numerous drawings were stored in jute sacks, and were to be hawked on the street at some later date.