Issue 4/2008 - My Religion

The Predicament of Religion

Twenty-First-Century Moral Politics in Latin America

Some of the most fashionable leftist intellectuals have gained prestige by celebrating Latin America’s naturally hybrid and creatively syncretic culture. Also lately there has been a lot of talk about the new Left turn of the continent, identified – with a little extra help from the opposition – with an egotistical, folklorish, neo-populist style, generalized in the figure of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. The region is the object of many carnevalized images of politics and culture, in which religion has a mystical omnipresence. This stereotype is of course, like all exaggerations, not completely inaccurate; but it also plays a part in underestimating the still very real power of conservative religious moral politics.

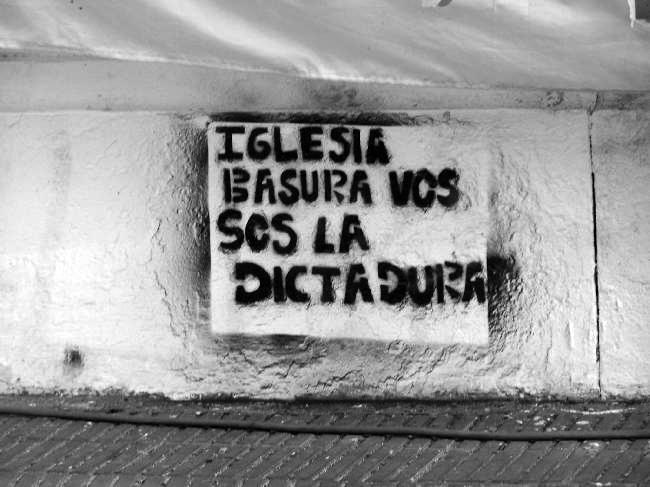

One of the more pragmatic and constant variables in this schema is the intervention and involvement of the Roman Catholic Church, not only in regional politics, but in all aspects of everyday life. Far from the emancipatory drive of Liberation Theology, today the Church operates as an increasingly efficient ultra-conservative force throughout the continent. Its highly populist participation in the public sphere is complemented by a more silent but quite effective opposition to any proposal for social transformation (we recall that the Catholic authorities were among the first to recognize the »new« government in the failed coup attempt against Chávez in 2002).

A few months ago, a Brazilian catholic priest, Adelir de Carli, was lost drifting over the Atlantic, armed with a skydiving helmet, a cell phone, a GDS radio (he unfortunately didn’t know how to use), and 1,000 helium party balloons. His »operação vuelo social,« a neopopulist solidarity crusade, wanted to beat the world record in cluster balloon flying and raise funds for a highway service station offering spiritual aid and shelter to truck drivers. Not exactly the traditional target group of a social campaign, but with the Church’s loss of devotees among the most poverty-stricken population in its most successful continent to the Protestant evangelist groups, a worthwhile effort. Fernando Lugo, an ex-bishop from Paraguay, is on a very different crusade. With significantly less media coverage, the recently elected president of Paraguay’s political involvement was bitterly opposed from the very beginning by the Holy See. Lugo’s intention of actually going beyond inoffensive, although sometimes tragic, marketing and paternalistic social work was intensely disapproved by the Church. The Vatican sent an official letter reprimanding him in the name of Jesus, on the grounds that politics is outside of religious incumbency, and strictly prohibited by Canon Law.

Many political scientists and theologists have insisted on the explosion of Protestant evangelist movements in the region, and the loss of Catholic reign in Latin America, especially among the poorer social groups. The most conservative sectors maintain that this is clear evidence of the definitive failure of Liberation Theology, which for decades overlooked the »emotional/personal« aspect of the spiritual message and insisted on salvation through social change. According to them, the evangelical preachers are gaining ground by insisting on personal salvation. This diagnosis has translated into a change of strategy, resulting among other things in Pope Benedict’s call for an »evangelical mission,« meaning all efforts for social change are to be dropped, and even condemned, while populist marketing strategies are emphasized and supported, especially oriented towards a popular mass audience. But is the Catholic Church really losing its grasp in Latin America?

Even within the Left, the hegemonic force of religious, specifically Catholic, ultra-conservatism is currently quite powerful. Many leaders of yesterday’s left-wing revolutionary movements, even those who were openly against the conservative interventionist policies of the Catholic Church, are today keen on spectacular demonstrations of respect for the oldest persisting institution in the region. There are many celebrity moments of tolerance and even devotion: Fidel Castro and Pope John Paul II waving away at the crowds in Havana in the late nineties; and last year Daniel Ortega’s wedding ceremony during the mass organized in homage to the twenty-five years of the Sandinista Revolution (coincidently during the presidential campaign that he later won). There is no doubt of the political convenience of such gestures, not only for international relations, but more importantly for local support, especially considering the fact that the region is still home to almost half of the world’s Catholic population. But what happens if we try to put aside the picturesque tactics of realpolitik, which are anyhow not so original, as a quick glimpse at right-wing European neopopulists could easily demonstrate. The question remains: Is a secular state an aspiration of the past?

[b]Catholicism as political institution?[/b]

Of course the fact that the Catholic Church is a political institution in the region is nothing new. At some point, its political strength was so strong that it effectively turned away from its traditional ties to the local industrial and landowning elites – not without a struggle – in order to articulate a potent emancipatory force in the Liberation Theology movement of the sixties. When the revolutionary movements of the sixties and seventies were repressed by a series of military coups, the Church found itself the only institution that could afford the »luxury« of sheltering dissidents, and it was ethically obliged to protest against the violation of human rights. In Brazil and Paraguay the opposition to the dictatorships was very fierce, and much more confrontational, keeping Liberation Theology as a constant reference (it is no coincidence that today Lula da Silva and Fernando Lugo have acknowledged their admiration and past links to the movement). Whereas in Chile its political outspokenness was more modest, the Church was equally important in its role of protecting and housing dissidents and denouncing human rights violations. There were of course exceptions, as in Argentina, where the Church collaborated more or less openly with the military regime.

There are many internal differences, national and regional, but all the authoritarian regimes of the seventies gave the Catholic institution a very precise and significant function, which in many cases meant moderating the more confrontational and critical stance in favor of its mediating role. In return, the Church gained the surplus of generalized social legitimation. As some have pointed out, this context strengthened the Church’s autonomy regarding the state, but at the same time it accommodated itself in its vigilante role, with international diplomatic approval. Evidently, the Holy See was not keen on retreating from this advantageous position during the re-democratization processes. And, in the eighties, the clear conservative turn of the Church benefited greatly from the terrain that had been gained. At this moment it officially condemned clergy involvement in political affairs, which was basically the reprimand of Liberation Theology and any sort of left-wing activism, while at the same time re-establishing itself as a factual power allied with the conservative local elites.

Today, there is clear regional intervention in public policies on issues such as divorce and abortion, which are not only far behind international basic standards but have in the last years suffered strong drawbacks. The latter is penalized in most countries, even in cases of rape, incest and life-threatening pregnancies. Here the Church’s involvement is blunt and direct, not only preaching its position through its strong links to local media, but also often accompanying its political lobby with expensive mass publicity campaigns. Chile only recently lost its status as one of the last two countries in the world with no divorce law, while this year witnessed a bizarre legislative strategy – directly orchestrated by the Church – to try and ban not only the »emergency day-after« pill, but also birth control methods that have been in use for over fifty years. (In response, the region’s first apostasy movement was born). Although Argentina’s civil society is more open to these issues – partially due to the clear identification of the Church with the dictatorship – they still have constant conflicts. In México City, the recent legalization and implementation of abortion in public hospitals by city legislators has been opposed by means of an obscure legal battle led by the Federal Government in alliance with ultraconservative Catholic groups. The latest pro-life manifestations disturbingly echo the imagery and tactics developed by human rights activists in their demands for justice for the thousands gone missing under military rule. Plastering the Zócalo with photocopies of headshot images of women who had an abortion (as was done with the military involved in torture cases), and placing white crosses for the »disappeared« are amongst the quite disturbing tactics of utterly confused and decontextualizing over-identifications. All of this is covered in the international press as typically South American dilemmas.

[b]Church and elite[/b]

But where does the local elite come in? Well-off Latin Americans are hard to associate with these images. Nonetheless, there is a complicity that goes further than the broad consensus that neoliberal policies are not to be touched and that the mere idea of social transformation is naïve and potentially dangerous (the vicious opposition and uprising of the privileged Bolivian upper class against Evo Morales is only one example). But how does the extreme (neo)liberal stance in the economic field, and the supposed Left political turn in the region conjugate with increasingly conservative value systems? While trying to seduce potential deserters with the latest religious populist strategies – in close association with major mass media networks (the Church directly owns some of the most influential television stations, and has strong ties to major newspapers) – the Holy See’s connections with the upper classes are of a slightly different nature than its efforts to compete with the shaking pastors of the popular evangelical movements.

One of the oldest and most effective manifestations of this historical alliance is education. The fundamental role of the Catholic Church in the private educational system, once prominently led – not without significant struggle – by the Jesuits, is now being defied by the increasing number of institutions run by Opus Dei and the Legion of Christ. It is not necessary, though, to look at the right-wing extremes, as some amazing efforts in justifying and perpetuating the embeddedness of Catholicism in Latin American culture, and its intromission in all aspects of life, can be found among prestigious social theorists who make up a surprisingly unquestioned conservative intelligentsia.

A striking example can be found in a prestigious group of academics running one of the most important sociology departments of the region1. Their research maintains that the »superior« cultural ethos of Latin America is Catholicism. For them, our lack of instrumental rationality and our inclination towards social relations based on intuition and sentimentality come from the fact that our ethos is pre-Enlightenment. What makes these organic intellectuals of religious essentialism unique, in opposition to similar arguments by some Hispanist, indigenist and anti-imperialist currents, is their insistence that secularization, and its subordination to a rationalist ethos, is the alienation that has doomed the region. The true identity to be embraced is Catholicism in its popular manifestations that have resisted all foreign influences, incarnating the »genuine and spontaneous« expression of our ethos2. In many ways, this celebration of our pre-modern culture can be linked to discourses that intend to articulate Latin America’s intrinsic postmodern, »other« logic as a counterculture to Modernity, also basing their arguments on the unique way Christianity has materialized in popular culture. These sociologists’ problematic overlooking of tiny details like historical social conflict, exploitation and power relations, along with their essentialist view of religion and culture, does not seem to bother the political elite. Even the local socialist government authorities seem convinced, and hire their professional services as consultants.

One of the region’s most prestigious »experts« in culture and education, José Joaquín Brunner, has been very innovative in reworking this position for the contemporary situation. After two hundred pages of celebrating postmodern culture, for its »hybrid form of tolerance and pluralism,« he points out that there is one troubling detail: »global inequality,« the »ethical-political contradiction of democratic capitalism.« He suggests that a revision of the Catholic Church’s ethical discourse could very well be the unexplored solution to the dilemma of postmodern indifference. A visionary follower of Ratzinger, our specialist sees the Vatican as a »deterritoralized community« with centuries of experience, one that can very well coexist with different historical subjects and provide at the same time the necessary ethical framework for global coordination, in a much more efficient way than secular international entities like UNESCO, which must simply accept a minimum common ground. The Vatican is discovered as absolutely compatible with global postmodern culture, prepared to guide the world through the parallel culture of faith where »truth and morality« are one3. This is only a slight shift from Paulo Freire’s version of »Veritatis Splendor,« back in the days when our progressive intellectuals believed that speaking the truth would in itself transform the world, and not moralize us all into stagnation.

1 The Sociology Department of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.

2 For an elaborated critique, see: Jorge Larraín, »Modernidad, razón e identidad en América Latina,« ed. by Andrés Bello, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, México, Santiago, 1996. pp.176-183.

3 José Joaquín Brunner, »Globalización Cultural y Postmodernidad,« Fondo de Cultura Económica, Barcelona, México, Buenos Aires, Santiago, 1998.