Issue 4/2008 - Net section

Fulfilled and unfulfilled hi/stories

Two Manifesta works explore the media-ecological and network effects of certain metals

One important approach adopted by engaged art involves making the invisible visible. For a long time now, Graham Harwood, Matsuko Yokokoji and Richard Wright (formerly Mongrel) have devoted their attention to rendering the repressed visible. In this endeavour their site-specific and –a novelty in art – media-ecological approach focuses over and over again on historical aspects between the poles of tension generated by the paradox of exploitative technologies that serve capitalism, yet at the same time offer scope for self-empowerment. Their most recent works, created for »The Rest of Now«, the section of Manifesta 7 curated by Raqs Media Collective in a decommissioned aluminium factory in Bolzano1, are sited in this combat zone.

[b]The book as machine[/b]

A cloud-filled sky with a winged sculpture of Eros floating in it. Then a woman, pushing a pram, and Eros and the clouds are nothing but shadows, gentle protrusions on the woman’s body. The wall on the left begins to move like a concertina, the pram becomes gigantic, a monster pram, until it is nothing but chassis and roof and pushes the woman out of the picture. Instead a wheel, ever more massive, ever more greedy, ever more clearly identifiable, pushes its way forward; it is the rear wheel of a car, coachwork with an air of the grotesque. It too is dragged out of shape, torn apart, gives way to another, no less gluttonous car body. Later these are followed by shelves full of tins and bottles, covers and packaging. And later still we see machines, hands working, an excavator shovel digging, men, trains, smelting processes. Always blurred, always in these images that drift apart, out-of-focus and disjointed, and then finally sharply defined: wheels, turbines, strips of aluminium.

»Aluminium« by Graham Harwood comprises a film and a catalogue, but is actually a net project based on two old advertising films about aluminium. Harwood worked on these with an algorithm to create an impression of artificial fragmentation and metallic disintegration. The images are no longer self-contained, for each always already contains parts of the subsequent and preceding images. This aesthetic of simultaneity and dynamism, as well as the old-fashioned air of the subject-matter are reminiscent of Futurist paintings, but, in contrast to such works, the images are process-based, mechanical, programmed and excessively abundant, in a way clogging everything up – as is made clear by the overwhelming number of shots from films reproduced in the associated catalogue. »How do we deal with excess? – The millions of texts? And millions of films?«, writes Graham Harwood, presenting his point of departure.2 He continues: »Marinetti’s use of violence as a kind of poetic hygienic measure shocked me, even 100 years later. I thought about the course of the 20th century: the atomic bomb, forced sterilisation, popular culture, Christmas trees bedecked with Aluminium and espresso machines made of aluminium, full of coffee from Ethiopia, with the 200,000 victims killed during the Italian invasion of the coffee plantations paying the price for producing this coffee. And I thought: yes, the 20th century has entirely fulfilled the Futurists’ dreams. They would have been proud. And at the centre of this pride stood aluminium, through which Futurism became part of our everyday lives.«

Here aluminium becomes a pars pro toto for an entire culture of violence and the glorification of the machine, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s nearly 100-year-old Futurist manifesto becomes an aesthetic anticipation of something that would come about subsequently. Harwood read it as a kind of »recipe«, which he transposed into code and wanted to run. That is how he came to devise his »Futurist algorithm«, which generated not only the machine aesthetic and production mode of his film but also »the book as a machine«. In this algorithm he wove together fragments of Marinetti’s manifestos and commands to generate the film images and texts about aluminium, compiled by an Issue Crawler on the Internet and conjoined to form a »social history of aluminium«. To put it in a nutshell, the film, the images and the text in the book, as well as the book itself, are products of one single »Futurist algorithm«. This reveals not only that everything is linked dynamically to everything else, and can be generated mechanically but also that everything obeys the logic of the capitalist machine, yet that is possible in a way to turn the code against itself and uncover other possibilities. The film therefore gives us a sense, for example, of the original ideologies of the »beauty, imperishability and lightness« of this »metal of the future«; at the same time however the blurriness, the superpositions and the non-coinciding seriality of the images also reveal something one might describe as their wild flipside. It looks as if the metal has been corroded or eaten into, has become waste or merely dross.

[b]A monument in motion[/b]

In the »Tantalum Memorial Project« too, a tripartite project in three locations3, created as a cooperation with Matsuko Yokokoji and Richard Wright, a metal determines the title of the work and establishes a »monument« as a pars pro toto of its repressed historical and media ecological connections. Tantalum is used for electronic devices such as mobile telephones, and sells at prices higher than those for silver. It is extracted from coltan, which is mined in locations including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and was a factor triggering the war in the Congo. Millions of people have been killed in this war over the last twelve years, mostly unnoticed by global public opinion.

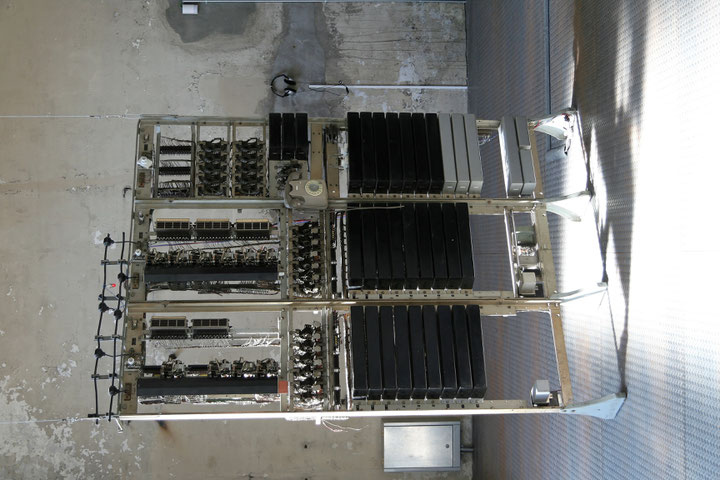

»Tantalum Memorial – Residue« at Manifesta 7 comprises a telephone exchange that rises up above head-height and is made up of Strowger switches from 1938, which were found in the factory and restored. On the opposite side are a computer and blinking modems, which now and then produce a strange rattling and clattering in the wires and switches of the old telephone exchange; from a headset further back we hear announcements in an African language. The clattering in the apparatus is produced by calls in the mobile telephone network »Telephone Trottoir«, to which it is linked. This network is a temporary social project implemented by the three artists in conjunction with the Congolese radio station Nostalgie Ya Mboka. It calls up its listeners at random and tells them a story from the coltan war. The people who have been called may respond, recommend other telephone numbers to call and on another line can introduce points they wish to discuss. The recordings of discussions are archived, translated into English and can be consulted via the Internet, although at present only the material from a 2006 pilot project is available. This reveals how keen people are to participate in discussions, especially because, as they stress over and over again, public discourse in the United Kingdom does not pay any heed at all to their opinions. The telephones make it possible for them to share their social and cultural conflicts with a community of like-minded people and to have a sense of being perceived as competent. However, within the framework of the »Tantalum Memorial Project«, »Telephone Trottoir« is also attempting, over and above its function in creating identity, to make repressed history directly accessible through narrations of oral histories.

In the exhibition no weight is given in the first instance to what is actually said. The installation kicks in on a more mechanical level, with the notion of rendering the functioning apparatus, switches and networks visible and audible right at the heart of the piece. Viewers are shown an old machine running under new circumstances and can see too that each component bears a story that can carry us further, as well as comprising scope for intervention. In this vein, the Strowger switches also conjure up a forgotten chunk of the history of technology and capitalism. The name of the switches comes from Almon Strowger, a 19th-century entrepreneur, who invented automatic telephone switching to shake off his snooping competitors. Richard Wright quite correctly describes the installation as a »syntactic constellation of conflicting forces, events and historical references, which combine some of their concrete manifestations, processes and residues in a quite literal manner«. To put it in a nutshell, the reconstruction of the analogue machines and the way in which they are linked up to a mobile telephone network does not merely connect various eras, technologies, ethnic groups and cultures, and this hybrid machine does not simply reveal to us the uninterruptedly violent nature of the capitalism machine. Its peculiar rattling and clattering, shaking and switching also reveals to us that other things – unheard of, never seen before – are afoot too.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Manifesta 7, The European Biennal of Contemporary Art, 19th July to 2nd November 2008; http://www.manifesta7.it/

2 All the quotations in the text stem from e-mail correspondence with the artists on 17th August 2008.

3 The »Tantalum Memorial Project« comprises Part 1 »Tantalum Memorial – Reconstruction« (0SJ Biennale, San Jose Museum of Art, 10th May to 31stAugust 2008), Part 2 »Tantalum Memorial – Residue« (Manifesta 7, Bolzano) and Part 3 »Tantalum Memorial – Reconstruction« (The Science Museum, London, October 2008); http://mediashed.org/TantalumMemorial