Issue 4/2008 - My Religion

Beyond democracy

On the relationship between art, the state and the church in Poland

Let me begin by showing two art works, which are to some extend very similar, yet which provoke different reactions. These are »Ninth Hour« by Maurizio Cattelan shown in 2000 at Zacheta Gallery, Warsaw, and showing the previous Pope pressed down by a meteorite that has come crashing down from outer space, on the one hand, and »The End of the First Five-Year Period« by Ciprian Muresan shown in 2004 in Romania at the Protokoll Gallery in Cluj. The latter work uses the same iconographic motif as Cattelan’s work, here however, related not to the Pope, but to the Romanian Patriarch, certainly an authority for Romanians. The former piece was destroyed by two Polish MPs, Witold Tomczak and Halina Nowina-Konopczyna, who removed the stone from the body of John Paul II. With reference to the second work, I would like to note that there was no reaction at all. What is also striking is that the prosecutor’s office, very active at that time in Poland in the art sphere, as I’ll be addressing later in this paper, refused to charge the two Polish MPs with an obvious act of vandalism and violation of the law on protection of objects of culture.

The Polish hysteria was in fact anticipated by a perfectly correct diagnosis by Harald Szeemann, curator of the exhibition at Zacheta, who decided that Cattelan’s work would be displayed. Organizing an exhibition of Polish art, Szeemann wanted to show something that would affect the »Polish visual sphere«. Since he did not find anything that fitted this description in Polish art, he resolved to include »Ninth Hour« in the show. I am sure that Szeemann was interested in Polish sensitivity to the effigy of the Pope, no doubt the key cult figure of the Polish imagination, so that he did not show John Paul II standing on the pedestal, heroic, and watching us from above, but – quite on the contrary – prostrate on the ground and pressed down by a meteorite. That was a genuine visual shock. Spectators could pass by the Pope’s lying figure, nearly stumbling onto it. To a certain extent, Szeemann attained his goal – he deconstructed our vision of John Paul II, but on the other hand, he failed, since Poles proved totally unable to analyze their visual attitude to the pontiff. Instead of reflection, they reacted with aggression performed by members of the political establishment. It is important to recall that Witold Tomczak, then a Member of the Lower Chamber of the Polish Parliament (Seym), and now a Member of the European Parliament, not only failed to apologize for his actions, but actually wrote a letter to the Minister of Culture, suggesting that Anda Rottenberg – and the authorities even went along with this recommendation.

Murean’s work was exhibited under completely different circumstances. First of all, it was constructed, as it were, according to Cattelan’s model. That particular point of reference was immediately obvious to the audience. In fact, then, the sculpture was not so much »about« the Patriarch, but »about« »Ninth Hour«. The reference to the Patriarch was mediated by another work and another person, which provoked quite different interpretations. In the first place, the Patriarch was compared to the Pope not only in terms of being the head of another Church, but also as someone who, like him, has to carry the burden – inter alia – of the ongoing secularization of social life. In Europe, this process is obvious whether Poles are aware of it or not; in Romania as well. In contrast to the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, which is now enjoying the aftermath of its support of independence movements in the 19th century and in communist times, the Romanian Orthodox Church is not triumphant. It is, however, very popular, maybe the most popular institution in Romania along with the army, even if its reputation has been damaged by its cooperation with the secret police (Securitate) during the communist dictatorship. Consequently, the faithful and the clergy in Romania have a very different attitude to the religious creed and its social function. Therefore, Murean’s work was received not so much as an assault, but as a metaphor of genuine care.

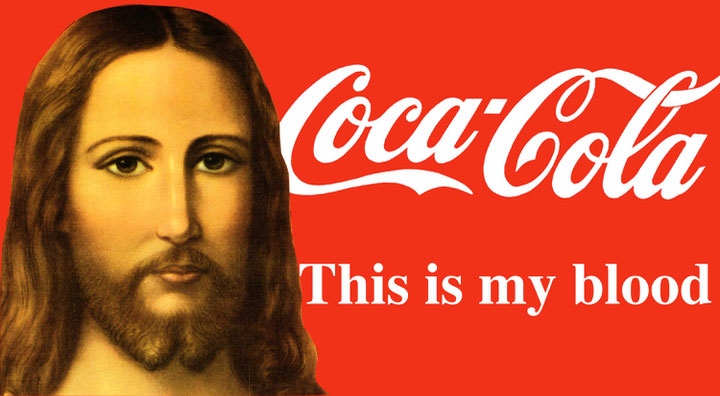

I have mentioned, and even contrasted those two art works, in order to make you aware that the relationship between art and the state in Poland, e.g. in the form of public prosecutors, was very difficult in the 1990s, and at the beginning of the 21st century, particularly over the religious iconography, and at the same time was almost unique among post-communist countries. I have said »almost«, since there was another country where one can find processes that are to some extent comparable. Thus, when now we ask in which countries the state and its organs are involved in prosecuting artists, the answer may prove to be surprising, but quite symptomatic. In »our« part of Europe there are only two such countries: Poland and Russia, since only there have individuals dealing with art been given court sentences. In Poland Dorota Nieznalska faces a sentence not yet in force; her personal freedom may be limited for six months by the court in, whilst in Russia a fine of 100,000 roubles has been imposed on two individuals. One of them is Yuri Samodurov, director of the Andrei Sakharov Human Rights Center in Moscow, the other is Ludmila Vasilkovskaya, the Center’s curator. Both the Polish artist and the Russian activists were punished for similar offences. In Nieznalska’s case, the »offence«»Passion«, or rather a fragment of her work, i.e. the Greek cross with a pasted-on photo of male genitals,1 while the Russians organized an exhibition called »Caution! Religion« (one of the most controversial works on display was Alexander Kosolapov’s »Coca-Cola, This Is My Blood«; fortunately, the artist himself remained beyond the reach of the Russian prosecutor, having lived for many years in New York) in early 2003 at the Sakharov Center.2

To compare Poland and Russia or, more precisely, Nieznalska’s »Passion« and »Caution! Religion«, let’s note that both affairs have revealed several problems. Even though the two countries are quite different – Poland is supposed to be free and democratic, being a member of the European Union, while Russia remains essentially autocratic, sometimes still violating human rights – there seems to be a rather striking similarity when it comes to the state’s involvement in prosecuting those involved in the visual arts. Another question pertains to the type of art that has been persecuted in Russia and Poland. It is art which uses religious iconography.

The Russian policy toward religion, particularly in the times of Vladimir Putin, has been (still is) quite opportunistic, and it appears that the President’s moves in this respect aim at a calculated political effect. In Poland, the problem is more complicated, as it seems to be related to the ideological character of the state. Since the principle of the separation of Church and State has been violated here, the latter took on responsibility for representing the Christian ideology, so that it may feel obliged to suppress those who do not share this ideology and manifest their opposition to it. If, then, in Russia the measures taken against art are par excellence opportunistic, in Poland their origins are more structural.

In fact, Dorota Nieznalska as well as Yuri Samodurov and Ludmila Vasilkovskaya have been sentenced for blasphemy. Therefore, their defense should have been based on the artist’s right to commit blasphemy, since it is in the citizens’ best interests to have this right, which is not always elegant, but which is much safer than its opposite. It is in the best interest of the citizens that their right to profanity be recognized both in religious and political terms, as – according to Giorgio Agamben – profanation means regaining what has been appropriated, repossessing what we have the right to possess.3 Apart from that, however, I believe that interpreting Nieznalska’s work and »Caution! Religion« as blasphemy is a matter of political manipulation. Nieznalska’s »Passion« consisted of two parts: the cross and a videotape showing a practicing man. That was quite a significant semantic context, often ignored or at best marginalized by the Polish media, implying that the work’s subject was the cult of the male body, so common in the consumer society. Body-building is now practiced by many men and women with a passion which can be understood both as zeal and suffering. Thus, the title may be only a potential reference to the Stations of the Cross. Let me add, that this is the Greek cross, not the Latin one on which Christ was crucified, and both the prosecutor and the judge should have been aware of that. The Greek cross is a symbol of the ideal, while genitals are a symbol of masculinity. Brought together in the context of passionately practiced physical exercises, they reveal the artist’s irony toward the male cult of the body so that the discursive reference to the Passion of Christ is thoroughly ironic, but the object of irony is not Christ – it is the cult of male body-building.

Let us now take a look at Alexander Kosolapov’s »Coca-Cola. This Is My Blood«. Unlike Dorota Nieznalska, Kosolapov is an artist with an international reputation (currently living in NYC), the author of many popular works which ironically reveal mass culture’s appropriation of ideological, historical, and religious symbols. Among his best known works are transformations of Coca-Cola and McDonald’s advertisements seen through the prism of Lenin (»It’s the Real Thing«, »McLenin’s«), Mickey Mouse stylized to resemble the famous Soviet sculpture by Vera Mukhina of 1937, »Male and Female Worker«, and »Malevich Sold Here«, imitating a Marlboro ad. Kosolapov’s rhetoric and style are definitely derived from soc-art or, more precisely, from the clash of soc-art with the consumer culture of the West. He is not interested in religion as such, which did not matter either to the Russian press or to the hooligans who destroyed the »Caution! Religion« exhibition, not to mention the state prosecutor. For Putin’s regime it was only a convenient pretext to prove to the Orthodox Church its »care« for the religiosity of the Russian people.

More than Russia or any other European country, Poland is particularly sensitive to the use of religious iconography in art, and Nieznalska’s case is just the tip of the iceberg, for the problem is much broader, although the case of »Caution! Religion« in Russia was no exception, either. A year after that exhibition, in February 2004, the S.P.A.S. Gallery in St. Petersburg, showing Oleg’s Yanuschevski’s portraits of well-known politicians in the form of traditional Orthodox icons, was devastated by hooligans as well. In January 2005, the »Russia 2« exhibition in Marat Gelman’s gallery also caused controversy. Still, contrary to the exhibition at the Sakharov Center, neither case gave rise to legal prosecution. Polish sensitivity to the issue of religious iconography has been influenced in recent years by the extremist radical groups close to Radio Maryja, which have also affected the political establishment. However, other traditionally controversial motifs, such as the body, obscenity or sexuality, provoke much less vigorous reactions. Regardless of the scope of comparison with Russia, it should be noted that Poland, as far as its particular sensitivity to the artistic use of religious iconography is concerned, is a unique and exceptional case among all the post-communist countries. I have opted to compare it with the Czech Republic, maybe the most liberal country in the region in that respect, in reference to the exhibition of Czech art called »Shadows of Humor« (Breslau),

[b]Censorship outside Poland[/b]

The »Shadows of Humor« exhibition was arranged by William Hollister, an American who has lived in Prague for years, who knew, of course, as everyone does, that Poland has a problem with art censorship. The first edition did not bring any serious problems, though at first it seemed difficulties would arise. In Wrocaw the Kamera Skura group presented its work entitled »SuperStart«, showing an acrobat taking the pose of Christ Crucified. The Liga Polskich Rodzin [League of the Polish Families], an extreme right-wing Christian-nationalist party, then a member of the ruling coalition together with the Law and Justice Party (PIS), voiced its disapproval, but no serious confrontation ensued. Incidentally, the work collapsed and disintegrated, thus eliminating a cause of potential conflict. It should be added that originally »SuperStart« had been prepared for the 2003 Biennale in Venice and displayed in the Czech and Slovak Pavilion (both countries still share the former pavilion of Czechoslovakia) as part of the official presentation by the Czech Republic. Interestingly, neither the Czechs nor the international audience at the Biennale raised any objections to it.

To make this account of the Polish censorship of Czech art in 2006 more complete, let me mention the case of the removal of a work by the Guma Guar group, called »You Are All Faggots« from the »Bad News« exhibition in Galeria Kronika in Bytom after just one day. The piece showed Pope Benedict XVI with the bloody severed head of Elton John, referring to the iconographic motif of Judith with the head of Holofernes, or also to David with the head of Goliath. Judith was a Jewish national heroine who, using her female charms, sneaked into the Assyrian camp and decapitated their commander, Holofernes, thus saving her compatriots. The story of David and Goliath also belongs to the Biblical context of the people of Israel fighting its oppressors, in this case the Philistines. David, smaller and weaker, defeated the giant Goliath and cut off his head, which contributed to saving the Jews. In the latter case, though, what is more important is the typological correspondence between Goliath’s defeat by David and Christ’s defeat of Satan in the New Testament, and this particular context is certainly more relevant to the work of Guma Guar, where the Pope defeats evil as represented by the gay singer.

In both versions of the classic iconographic scheme, the crucial element is a heroic deed which saves the people from oppression or, in broader terms, which symbolizes the victory of good over evil. However, Benedict XVI, Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, which is known for its homophobia, showing the head of Elton John, a known gay, means also, or perhaps in the first place, the triumph of oppression and the politics of exclusion. The meaning of the work is obviously determined by its title, »You Are All Faggots«. This is the evil against which the Church is struggling; this is the accusation and the threat of punishment awaits us, since we are all faggots – all of us who do not think as the Church would like us to think. Thus we are condemned to follow in the footsteps of Holofernes and Goliath… The answer which we ought to give to Benedict XVI is prompted by the French students who defended Daniel Cohn-Bendit against their own (i.e. French) government in May 1968, shouting that they were all »German Jews«. It was a clear gesture of solidarity. No doubt, the Guma Guar group seems to be telling us, for the sake of democracy we ought to make such a gesture of solidarity with sexual minorities – gays and lesbians.

The above story is, however, not about interpretation, but about censorship. No matter what the meaning of the work might be, nothing justified censoring it, particularly under the pressure of the right-wing press. »You Are All Faggots« was shown as part of the »Bad News« exhibition and already on the next day, as a consequence of critical reviews published by the right-wing press, the curator decided to remove it from the display. The press, regardless of its political orientation, has the right to criticize. This is its role. Certainly, it expresses the views of some of its readers, but this does not mean that a curator must turn into a censor under the influence of criticism. As the term itself clearly suggests, the curator should take care of art and not censor it; s/he is supposed to defend it against attacks, and not render the artist mute for some opportunistic reason. Moreover, it is the spectator who has the right to decide whether a given work is good or bad, relevant or not. No one can deprive the audience of a chance to develop their own independent opinions. The censor deprives the viewer of a chance to pass his or her judgment by taking a decision for others. In a democratic society, where citizens represent different individual views, such a situation must be treated as a violation of their liberty.

The stories described above are just the tip of the iceberg of Polish experience in terms of the debate on controversy over using religious iconography in contemporary art. I am not going to go into the details of it4, however, it is worth saying a few words about the political meaning of the exhibition »Irreligion. The Morphology of the Non-Sacred in Polish Art of the 20th Century«. It was shown in Brussels simultaneously at several locations, including two churches (one still a place of worship, the other no longer functioning as a centre of religious services) in 2001–2002. Since the exhibition overlapped with a kind of festival of Polish culture in the bureaucratic capital of »United Europe« – an event in a series called »Europalia« presenting art from the then candidate countries of the European Union – the exhibition could have become a part of it, but the supervisors representing the Polish administration refused to include »Irreligion« in an official presentation of Polish artistic culture. The show’s non-official status implied an open conflict with the Polish right who claimed that their country could »enter« Europe only under the banner of Catholicism, protecting its national and religious identity. Thus, when the exhibition organizers questioned the right of the Church to control religious symbols, it was interpreted as an attack on this political strategy – a particularly vicious one since it occurred not at home, but in the very heart of United Europe. As a result, the exhibition became the focus of a political conflict in which the issues at stake were the public status of dissident visual culture and the access to public life granted to those who do not share the views of the Catholic majority. Two works were particularly in the line of fire. One of them was »The Whipping of Christ« by Marek Sobczyk (1987), the second one Andrzej Rzepecki’s »Our Lady of Czstochowa with Painted Moustache« (1982), originally published as an underground magazine cover page during martial law in Poland. In a word, Sobczyk was attacked because some people were of the opinion that the whips used by Christ’s tormentors suggested that they were urinating on the Saviour. Rzepecki’s case had a slightly different background. In his work he referred not so much to the original stochowa icon, but to its functioning in the underground »Solidarity« movement.urs of the Polish flag, it often appeared as a mascot5 traditions. Both converge in the strong Polish cult of Holy Mary as the »Queen of Poland«. religious worship and that of national identity.

[b]National autonomy[/b]

Finally, I want to ask a fundamental question: why the censorship of art in Poland, particularly over religious iconography, is tolerated, or at least, why the local reaction to it has been so feeble?

First of all, let me stress that our subject matter is art or visual culture, which in Poland never (with the exception of history painting at the end of the 19th century) enjoyed a particularly high status. In Poland there is almost no tradition of defending the freedom of art, in contrast with that of literature. Art has usually been perceived as an activity pursued by eccentric individuals who like to scandalize and shock decent society so that – as such – it was not worth protecting, once more, except when it touched upon the issue of national history. Literature has been appreciated much more highly as a repository of the nation’s ideas and emotions, as a hotbed of utopias and programs of spiritual renewal. The censorship of literature has been considered an assault on independence. In this respect, what is particularly interesting is the history of censorship in communist Poland, which practically ignored visual culture, particularly from the 1970s, instead paying excessive attention to literature. It is interesting that even the League of Polish Families has not yet interfered with the written word, and while the prosecutors have been monitoring the visual arts, they have not touched literature. I believe that the censorship of the latter is fortunately still a taboo in the wake of the experience of communism.

The relatively low status of the visual arts seems to derive from the model of Polish education in which artistic culture has never played a significant role. As a result, so-called patriotic education and social commitment, which constitute the tradition of the Polish intelligentsia, usually developed outside the realm of the visual (once more, with the exception of history painting). Perhaps, however, there is something more to it. I believe that Polish intellectuals have been educated to protect collective liberty, i.e. the political independence of the nation, and not individual freedom. To defend political independence, they were able to perform all kinds of heroic deeds, while the freedom of individual expression did not matter much. Of course, last but not least, historically the tradition of Polish independence has been connected with religion. Most Poles have considered themselves Roman Catholics – the sacrifice of personal liberty and life definitely had religious overtones, and hopes for national independence were often expressed via religious symbolism. In general, the Polish tradition of individual identity, transgression, and atheism, as well as profanity in respect of religion, has been weak. The decades of communist rule augmented conservative tendencies in Polish culture; this tradition, with both its positive and negative aspects, was taken over by Solidarity, which was largely responsible for the Polish mentality in the 1990s.

Conservatism, religiosity, little respect for individual identity or liberty, no tradition of intellectual, sexual, and cultural transgression – in fact no tolerance for otherness and difference, are all typical features of a colonized society. In the 19th century, Poland was a colonized country – perhaps unlike India, Pakistan, Africa or South America, but in its own way. The decades following 1945 were a period of another colonization, even though formally communist Poland was an independent state and had its own culture. Again, those circumstances favored cultural conservatism. What is interesting, though, is that the Poles were not the only victims of Soviet colonization – what is more, in comparison with the Czechs, Slovaks, Germans from the GDR, Romanians, Hungarians, and others, we were perhaps the least colonized; why, then, after the fall of communism did the censorship of art appear as a significant phenomenon in Poland, not in other post-communist countries?

Obviously we realize that in Poland the Christian-nationalist ideology was the dominant response to the political situation in the 19th century: there was no sovereign Polish state and society underwent colonization. However, we live at the beginning of the 21st century right now, when political circumstances are radically different. Therefore, we should expect that both politicians and the intelligentsia will abandon their anachronistic system of values and face the challenges of the modern world, including the need to develop democracy, the respect for individual identity and cultural, sexual, and religious difference, the defense of pluralism and otherness, the primacy of the freedom of speech, etc.

1 For a more detailed account see Piotr Piotrowski, Agoraphobia after Communism, Umeni, Prague, 2004, No. 1, and Piotr Piotrowski, »Beyond Democracy«, Centropa, New York, 2008, Vol. 8, No1, where a different and longer version of this article was originally published.

2 See http://www.geocities.com/aakovalev/religia-en.htm?200618

3 See Giorgio Agamben, Profanazioni. Nottotempo 2005

4 See: Piotr Piotrowski, Visual Art Policy in Poland: 1 For a more detailed account see Piotr Piotrowski, Agoraphobia after Communism, Umni, Prague, 2004, No. 1, and Piotr Piotrowski, “Beyond Democracy,” Centropa, New York, 2008, Vol. 8, No1, where a different and longer version of this article was originally published.

5 Izabela Kowalczyk, Tabu irreligii [The Taboo of Irreligion], Czas Kultury, No. 1 (2002), p. 69