Issue 4/2008 - My Religion

Performing the Veil

On the links between concealment, Enlightenment fundamentalism and the imperative of visualization.

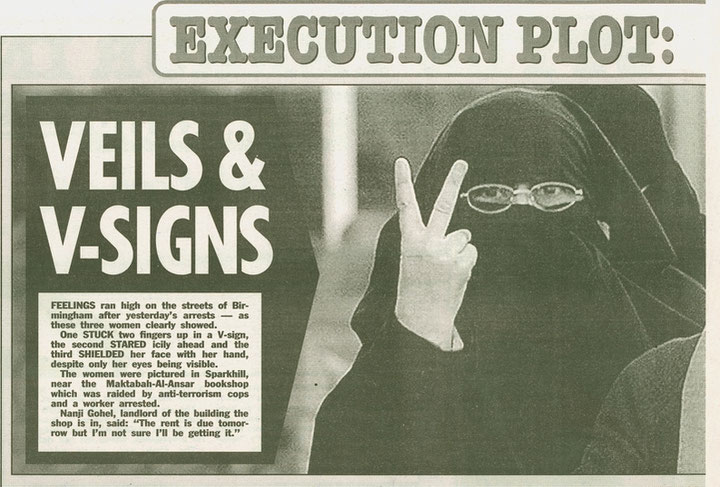

After a group of radical Muslims, who allegedly plotted to kidnap and kill a British Muslim soldier on leave from Iraq, was arrested in early 2007, British newspapers showed a photo of three veiled women in Birmingham, one of them making a V-sign.1 Although this is an extreme case, images of veiled women have become a minor genre in European newspapers. Photographs of Muslim women—either with headscarves or full veils—walking in front of billboards with scantily clad advertising sirens, drive home the point that the spectacle commodifies bodies just as it sexualizes commodities, and that Muslim women show their dissent and difference from the Western visual and economical regime by shrouding themselves. The most potent images are of full veils such as the niqab, which leaves the eyes visible through a narrow slit, and the Afghan burqa, which covers the eyes with an embroidered grille. As the emergence of a small number of women donning such apparel in major European cities over the last few years has been experienced as a radical contestation of the Western regime of visibility, the veil has come to function as a screen onto which cultural anxieties and desires are projected—and not just from one side. In the process, Orientalist fantasies and fears are rekindled: associated with Islam, the veil becomes an emblem for the otherness of Islamic-»oriental« culture and its incompatibility with »the West«.2 Under these conditions, Islam itself comes to be represented as an alluring, elusive and vaguely threatening woman waiting to be »unveiled«.3

When German archeologist and development worker Susanne Osthoff was released by her Iraqi kidnappers in December 2005, the German media rejoiced; when she decided to give an interview to the ZDF news program in a black veil that obscured her face, the sympathy immediately changed into irritation and doubts about her sanity. Within minutes, Osthoff had changed from »our Susanne« into one of »them«, less a person than an instantiation of a powerful iconography.4 But although the identification of the veil with Islam is a powerful one, various historians and theorists have pointed out that there is no exclusive or »natural« relationship between the veil and Islam. Not only were statues of goddesses often veiled in the Middle East and the Mediterranean region, wives were veiled as well, long before the advent of Islam. In the Mediterranean area and the Middle East, the veil – which predates Islam or Christianity – often had social rather than religious connotations.5 While the veiled image of a goddess signified the inaccessibility and otherness of the sacred, the veil worn by a wife on the contrary traditionally signified her status as a man’s property, in contrast to the unveiled prostitute. However, the woman’s veil can change its meaning: if the veil on a woman primarily signified that she was accessible only for her husband and inaccessible to the gaze (and touch) of others, this connotation of inaccessibility can be sacralized. This, it would seem, is what happened in Islam; whereas Christianity turned marriage into a sacrament, Islam sacralizes the female body by veiling it.6

During her years in Holland, Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote the script for a short film on the role of women in Islam, »Submission (Part 1)«.7 The 2004 film was directed by Theo van Gogh, the filmmaker and enfant terrible who for years dabbled in anti-Semitic rhetoric, which was then effortlessly transformed into anti-Islam rhetoric; Van Gogh famously described Muslims as backward ›goat-fuckers‹. He paid with his life for »Submission« when he was stabbed to death on an Amsterdam street in broad daylight by a young fundamentalist now famous as Mohammed B.8 »Submission« shows a woman wearing a dark but transparent veil that reveals parts of her body, upon which Quranic verses on woman’s submissive role have been written in ornate calligraphy. Here the role of the camera in unveiling the body, the fight between veil and camera over visibility, is restaged with crypto-pornographic explicitness. The film’s voice-over monologue contains harrowing stories of various forms of abuse, and depicts the veil as a prison, the innermost circle of an extremely restricted world. In many cases this is no doubt all too true, yet Hirsi Ali and Van Gogh participate in the reduction of the veil’s ambiguity and contradictions in favor of a cartoon image, thus turning women wearing hijab into the faceless face of otherness, and refusing to address the obverse side of the violence cloaked by the veil: the violence of unveiling.9

It is a fallacy to claim – as is often done – that all Islamic veils must under all circumstances be instruments of oppression. Many women claim the veil for themselves, for a variety of – sometimes contradictory – reasons. How to explain the sight of a woman demonstrating with a placard saying »The veil is women’s [sic] liberation?«10 For all the women who oppose the veil, there are countless others who adopt it to signify their otherness in and against this regime, their non-identity. Of course, those women who fight a forceful imposition of the veil deserve our full support, but while it is clear that today there are serious issues with women’s rights in many Muslim societies, as well as among certain immigrant communities in Europe, the fixation on the veil suggests that other issues are at stake as well, and that feminism is often being instrumentalized to rather dubious ends – there have been plenty of strange alliances between feminists and Islam-bashing right-wing Enlightenment fundamentalists, who find their favorite bête noire in the veil. The overt aim of »rescuing« women from a patriarchal regime can easily become the latest version of cultural colonialism, in which Islam as such is presented as the dark Other of European civilization; the real purpose of such rhetoric. Lord Cromer, the British Consul General in Egypt during the late nineteenth century, set a telling precedent: he already ideologized the veil as a sign of the Islamic oppression of women while opposing universal suffrage at home.11 Thus the issue seems to be less one of women’s rights and more one of the instrumentalization of women’s rights.

The repetition of images of veiled women serves to fortify the status quo; using the veil as Exhibit A, many authors present the integration of Muslim populations into »Western« history as unthinkable. When the Dutch minister for immigration, Ella Vogelaar, suggested that in the distant future there may be a »Judeo-Christian-Muslim« tradition in Holland, the main result of her remark was a vicious right-wing shitstorm.12 The historicity of religions and their relationships is consistently being denied; anti-Semites ranging from Martin Luther to Houston Stewart Chamberlain would be baffled by the current popularity which the epithet »Judeo-Christian« enjoys among those who wish to define and defend the essence of »Western civilization«.

[b]Abstract bodies[/b]

In Peter de Wit’s »Sigmund«, a popular daily comic strip in a Dutch newspaper, there are regular appearances by burqa-clad women drawn like cone-shaped black blobs—dark voids in the field of vision. In one episode, two of these »burqa babes«, seen from behind, are standing in front of abstract paintings in a museum, effectively becoming part of the composition. One of the women is saying to the other »I don’t like art where I can’t see what it represents«.13 In this probably unwitting variation on an old Ad Reinhardt cartoon, De Wit neatly encapsulates the strange structural homology between aesthetic modernism and Islamic culture in the contemporary imagination; both threaten to break with the apparently unhindered visibility with which »the West« is often identified. Islamic fundamentalists and Western »Enlightenment fundamentalists« both attempt to exacerbate this break. Both sides, the defenders of »the West« as well as its enemies, identify Western culture with a regime of total visibility, with an unhindered gaze whose favorite object has long been the female body. However, the seemingly complete opposition between the Western gaze and the veil as its blind spot is hardly that clear-cut. In many ways, the veil is complicit in the regime it appears to oppose.

What is disavowed is the abstract obverse of the images which contemporary capitalism produces in such abundance – an obverse for which the burqa, a black speck in the field of vision, might stand as a surprisingly neo-modernist emblem. Like the black masks and clothes worn by the mythical »Black Bloc« of anti-globalist protests, the veil seems to signal a radical break in the spectacular order. In their video »Get Rid of Yourself«, Bernadette Corporation investigate this Black Bloc, its strategies and its myths, at one point including an image of Malevich lying in state under his Black Square—thus linking contemporary political contestation in and of the spectacle to modernist iconoclasm that was itself, in Malevich’s case, informed by anarchist political sympathies. While there is obviously no such more or less direct link in the case of the burqa or the niqab, its use has a similar media effect; it is presented as blackout of the visible that amounts as a declaration of war on »Western values«.

Although there is no essential connection between the veil and Islam – the Qur’an does not prescribe the veiling of women, and Mohammed was a »liberal« in this regard –, today many Muslims use the veil precisely as a marker of a space beyond the grasp of the secular and sexual gaze. Ever since Sayyid Qutb, Islamists have regarded the comparative sexual freedom and the sexualisation of the public sphere as crucial symptoms of the new Western idolatry. It is not only that thought itself is turned into an idol by the Western rationalists, as Qutb stated with horror; sinking even lower than that, the westerners also idolize the body.14 But then, perhaps this is just a front for the true idolatry: as Ali Shariati stated, sexual freedom is »part of a new exploitation, a type of limitless deception, which the impure system of Western capitalism produces.« Behind the seductive appearance of commodified sexuality lie »great idols and the three faces of the contemporary religious trinity: exploitation, colonialization and despotism«.15 This may be true, but it is hard to avoid the feeling that Shariati is all too keen to attack sexual freedom as such. In this he comes close to Khomeini, whose »Little Green Book« starts with attacks on imperialism and colonialism, only to move on to insanely detailed proscriptions for dealing with sexuality and with »woman and her periods«.

A mural in the Iranian town of Susa shows a woman in Islamic dress, her face visible but her body concealed, her eyes modestly averted, and the accompanying text proclaims: »A woman modestly dressed is as a pearl in it’s shell« [sic].16 In Iran and elsewhere, a strict interpretation of hijab – of »decorous clothing« – has been forcefully imposed on women, in response to what conservative clerics see as the westernization and sexualisation of Muslim societies during the early- to mid-twentieth century. The ideological counterpart of this exercise in public art was executed in 2003 on the side wall of an Amsterdam tenement: a large mural of an undressed woman. The piece was inspired by a poem by Jacob van Lennep, »Ode aan een roosje«, which is splashed across the façade and across the body of the woman; a clothed man, presumably the author, floats over the text and the woman’s legs. Although the inhabitants of the neighboring buildings, many of them Muslims, were polled prior to the work’s execution, apparently with largely positive results, once completed the mural was attacked both verbally and physically, with black paint. When struggling to remove this paint, the artist decided to pixilate the woman’s pubic area, turning it into an abstract grid veiling the »origine du monde«.17

As in the case of Gerhard Richter’s new abstract window for Cologne cathedral, which Cardinal Meisner famously characterized as being more suited for a mosque than for a Catholic place of worship, abstraction again comes to be identified with Islam – this time with gendered connotations. A quasi-Richterian color grid once more appears to externalize abstraction.18 Abstraction is thus identified with the Oriental, Muslim Other, and the use of abstract forms and structures becomes suspect. This is not only a disavowal of the history of Western abstract art, but also of the abstraction inherent in the spectacle itself. Marxian theory contends that commodities are merely »pseudo-concrete«; on the basis of certain passages in Marx’s writings, various theorists have argued that under capitalism abstraction is no longer purely »ideal« or conceptual, but a social reality. It is the »real abstraction« of labor-power and, by extension, of all exchange.19 Marx, who famously dismissed religion as a »mystical veil« preventing a clear view of society, defines labor-power as »labor in the abstract«.20 Capitalism is built on the discrepancy between this abstract commodity – the worker’s potential to perform labor during a certain time – and the actual labor performed by the worker. If the seemingly physical commodity is really abstract, abstraction itself is a concrete reality. Guy Debord noted that »the abstract nature of all individual work, as of production in general, finds perfect expression in the spectacle, whose very »manner of being concrete is, precisely, abstraction.«21

For Debord, there was no point to modernist, formal abstraction in art, as all »artistic productions are now signs of nothing but abstract commerce.«22 Going beyond this reductionist reading, one might argue that abstract works of art are eccentric and problematic commodities, which become exemplary and illuminating precisely because of this exceptional status. Freed from its fundamentalist instrumentalizations, the veil could yet play a similar role.

[b]Living commodities[/b]

In the early »Philosophical and Economic Manuscripts«, Marx went further in his analysis of labour, claiming that the labourer as such is effectively turned into a commodity. »Production does not simply produce man as a commodity, the human commodity, man in the role of commodity; it produces him in keeping with this role as a mentally and physically dehumanised being. – Immorality, deformity, and dulling of the workers and the capitalists. – Its product is the self-conscious and self-acting commodity ... the human commodity....«23 The later Marx would not expand on this, perhaps considering the notion of a living commodity overly literary and imprecise, and opting for the more scientific notion of labor-power.

However, the underdeveloped and abandoned Marxian concept of the living commodity seems an apt description for what is often termed post-Fordist capitalism, in which workers are increasingly ideologized not as drones who sell their more or less interchangeable labour-power, but as creative, inspired individuals who bring something unique to the team. Today, many employees – and freelancers – are expected to bring their unique personality to the job, within certain limits. This goes both for those who perform in jobs demanding »soft skills« and for those who do seemingly purely technical work; at a company like Google, employees are encouraged to »be themselves«, to spend time in play, which demands a self-performance unlike the abstract roles required in the Fordist economy. It is important to stress that this is not a break with real abstraction. If anything, it is a dissimulation of the reality of abstraction, which becomes ever more »embodied« in an age in which biotechnology enables scientific, conceptual abstraction to penetrate the fabric of life itself. Thus the living commodity is increasingly penetrated by conceptual abstraction as well as by the real abstraction of exchange.

In a moralizing, puritanical, and overly abstract way, Islamic thinkers early on theorized the commodification of the human subject itself. When labor becomes less routine and increasingly demands »soft skills«, life becomes perpetual self-performance. The theatrical metaphor that is at the basis of the notion of the spectacle must be reinterpreted here: in Guy Debord’s classical 1960s formulation, the spectacle was based on the interplay of commodities that were both objects and images – distorted images of alienated labor. The relations between commodity-objects stood in for social relations. However, the rise of immaterial labor, which was already well under way when Debord wrote »The Society of the Spectacle«, means that the commodity increasingly takes on human form: as self-performers, we ourselves are the commodities. Veils are hardly a full break with this performative spectacle, or regime of immaterial labor; they are perfect props for generating attention. Presumably the V-sign woman was not paid for her act, and her commodification in the media does not benefit her financially; one step removed from the market, she provides an extreme form of contemporary self-performance.

As instrumentalized by both by religious fundamentalists and by Western »Enlightenment fundamentalists«, the veil disavows its own entanglement in the regime of enacted abstraction. For both sides, it represents an abstract negation, pure Otherness. Paradoxically, this means that it can easily be reabsorbed and neutralized by the symbolic order, just as the media success of the Black Bloc shows that it is eagerly appropriated by the other side, and functions as the perfect bogeyman. Can this indispensable performative prop for both camps be made to perform a different script? In recent years, Dutch artist Fransje Killaars, who in the early 1990s switched from painting to making installations with textiles, has taken to draping some of her bedspreads, with their brightly colored grids, on tailor’s dummies. These abstract and impractical full-body veils draw attention to their materiality and sensuality – to their own surface and texture rather than their status as obstructions of the gaze, as a hindrance to seeing what lies beneath. Titled »Figures« and posed in groups, they form a constellation that invites comparison and contrast.

Usually, Killaars also shows one or two dummies that are not covered in the manner of a burqa, but around which a bedspread is draped from the neck down in the manner of a cape. In contrast to the ›burqa‹ »Figures«, the ›cape‹ »Figures« use dummies whose heads have been removed; the cape is crowned by nothing. By »exposing« the veiled face as a void, these »acéphales« join the other works in privileging the cover over the covered, the veil over the veiled. Again the veil is here linked to modernist abstraction, but with a crucial difference: whereas in the Roosje mural the pixilated squares are clearly a veiling of the censored »reality« underneath, here the blankets themselves are the focus. Underneath, after all, are just dummies. Killaars’ »Figures« make the veil, and abstraction, visible as something integral to the figure rather than merely an obstruction. The abstract veil no longer occludes the figure; it »is« the figure.

Thus these pieces suggest the need to go beyond the abstract opposition between Western body and »Oriental« veil, and to study the fundamental complicity between the rise of the veil and the performative spectacle. Even if the veil seems to strike fear in the heart of the ideologists of the contemporary neo-imperial West, its political potential is curtailed by its status as a mystification – of women, of oppression and inequality in relations, and indeed of Islam. The specter of Veiled Islam being the perfect bogeyman to prevent any serious contestation of the current political-economical order, the task at hand is to unveil the veil itself, and to use it in ways that are tactical rather than dogmatic, motivated by an engagement with the present rather than by its abstract negation.

This text is an edited excerpt from »Idols of the Market: Modern Iconoclasm and the Fundamentalist Spectacle«.

1 See for instance »The Sun«, Thursday, February 1, 2007, pp 8-9.

2 In many ways, contemporary discourse on Islam is the contemporary version of the nineteenth century Orientalist discourse famously analyzed by Edward Said in »Orientalism«; the analysis of Orientalist interpretations/characterizations of Islam plays an important part in Said´s book, and is quite illuminating under present conditions. Said himself notes the persistence of Orientalist tropes in »contemporary« studies of Islam; Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978), pp 300-301.

3 On the cover of a book called »Unveiling Islam« by two Christian authors (Ergun Mehmet Caner and Emir Fethi Caner, Unveiling Islam, Grand Rapids: Kreger, 2002), the viewer’s gaze is met by a dark-haired woman whose head is partially wrapped in a white cloth; the veiled woman becomes the personification of »Oriental« Islam. Historically, Truth and Nature were often shown as female figures in the process of being unveiled. (On representations around 1800 of a sculpture of Isis, identified with Nature, being unveiled: see Jan Assmann, Moses der Ägypter: Entzifferung einer Gedächtnisspur (Munich/Vienna: Hanser, 1998 pp. 186/205). In this contemporary version, what is at stake is the unveiling of something seen as a falsehood and unnatural.

4 The interview with anchorwoman Marietta Slomka – whose blonde hair provided the optimum contrast with Osthoff’s black garment – was broadcast on December 28, 2005.

5 Christina von Braun and Bettina Mathes, Verschleierte Wirklichkeit: Die Frau, der Islam und der Westen (Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 2007), pp. 52-59.

6 Von Braun and Mathes, pp.101-102

7 »Submission« is a literal translation of Islam, and means »submission to God«; for Hirsi Ali, of course, the term primarily refers to the oppression of women.

8 In Holland, the media do not publish the names of suspects and convicted criminals, even though – when it comes to prominent court cases and convictions – this is by now an anachronism, since it is easy to find the full names online.

9 When Hirsi Ali criticizes the silence of »moderate« Muslims in cases of questions of violence against women, she has a point in so far as there is hardly a vibrant critical public sphere in large parts of the Muslim world, which has suffered a catastrophic intellectual and cultural decline over the last centuries. Hirsi Ali’s criticism becomes demagogy when she uses decontextualized Qu’ran suras – equivalents for which can be found in many other holy books – to suggest that Islam as such is primitive and beyond reform, and that essentially no Muslim thinks that practices such as brutal punishments for rape victims should be condemned. As Tariq Ramadan and others rightly point out, he and others actually did condemn such practices – as well as the jailing of hapless teachers who allowed their pupils to name a teddy bear Mohammed –, paying for this with a persona non grata status in many countries. Moreover, their criticism may actually make some difference in the long run – in contrast to Hirsi Ali’s diatribes, which appear excessive and unilateral.

10 A photograph of women holding this and other slogans, taken at a demonstration in Jack Straw’s constituency of Blackburn on October 14, 2006, can be found – for instance – here: http://www.theage.com.au/news/world/taking-cover/2006/10/15/1160850812211.html . Neurath’s remark on the veil is in Modern Man in the Making (New York/London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1939), p. 115.

11 Von Braun and Mathes, pp. 311-313.

12 For Vogelaar’s original statement in an interview with Trouw, July 14, 2007, see http://www.trouw.nl/deverdieping/overigeartikelen/article750192.ece/Help_de_islam_zich_te_wortelen_in_Nederland

13 The »burqa babe« installments of Sigmund have been published as Peter de Wit, Burka Babes (Amsterdam: De Harmonie, 2007).

14 Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit, Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Ites Enemies (London etc: Penguin, 2004), p. 117.

15 Ali Shariati, Fatima is Fatima, http://www.iranchamber.com/personalities/ashariati/works/fatima_is_fatima2.php

16 I became acquainted with the Susa mural through a photo by Frank Denys.

17 See the statement by artist Rombout Oomen on http://www.romboutoomen.eu/category/archief-archives/

18 Meisner, it should be noted, said »a mosque or a house of prayer«, the latter term suggesting a Jewish or Protestant place of worship, but it was the mention of the mosque that attracted the most attention. For Richter’s response to the mosque comparison, see Georg Imdahl, »Meisner irrt sich ein bisschen«, Kölner Stadt Anzeiger, 31st August 2007, http://www.ksta.de/html/artikel/1187344877397.shtml

19 Anselm Jappe uses the term »Realabstraktion« on the basis of a passage in the first edition of »Capital«. Anselm Jappe, Die Abenteuer der Ware: Für eine neue Wertkritik (Münster: Unrast, 2005), pp. 35-36.

20 Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, volume one (1867), translated by Ben Fowkes (London etc.: Penguin, 1990), 173, p. 226.

21 »[…] l’abstraction de tout travail particulier et l’abstraction générale de la production d’ensemble se traduisent parfaitement dans le spectacle, dont le mode d’être concret est justement l’abstraction.« Guy Debord, La Société du Spectacle (1967) (Paris: Gallimard, 1992), p. 30. English translation by Donald Nicholson-Smith at http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/tsots01.html

22 (Author’s translation.) »Aussi peu intéressantes que les timbres-postes oblitérés, et forcément aussi peu variées qu’eux, les productions littéraires ou plastiques ne sont plus les signes que d’un commerce abstrait.« (Michèle Bernstein et al., »Les Distances à garder«, in: Potlatch, no. 19 (April 1955). See Guy Debord présente Potlatch (1954-1957), Paris 1996, p. 144.)

23 Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, translated by Martin Milligan (Amherst: Prometheus, 1988), pp. 69-71.