Issue 1/2009 - Art on Demand

Architectures of spectacle

Facets of the exhibition boom in South Korea and China in the context of the strategy of globalism

In fall 2008 the Pacific region and in particular Asia hosted ten major biennials and other mega exhibition projects, in Sidney, Gwangju, Busan, Ghuangzhou, Shanghai, Singapore, Seoul, Yokohama, Taipei, and Christchurch. This marathon-like accumulation of grandiosity eclipses by far last year’s »Grand Tour« – a series of exhibitions and art fairs that took place in the European cities Kassel, Münster, Venice and Basel, and had already challenged the time capacity and mobility of the art world as well as art-loving tourists. The sheer extent of both series of eventsfuelled the critique that naturally grew out of the so-called »Biennale fever« of the nineties, namely, concern at an increasingly arbitrary exhibition boom, frequently featuring the same art stars using a specific, often similar media language.

However, it will be argued here that vast differences exist between these large-scale exhibitions, in terms of presentation, argumentative production of meaning represented through the art works, conceptual framework, and their embedding in the histories of nation-state and specific local conditions.

[b]Context and Goals[/b]

In states such as China and South Korea, which in the last two decades have experienced major transformation processes of an enormous pace and scale, the cultural industry plays a key role in the redefinition of identity. This involves the opening up and strengthening of Chinese and South Korean distinctiveness on a cultural level; the emergence of biennials and other mega exhibition events is one result. The enormous popularity of biennials in emerging economies like South Korea and China provides a basis for reappraising the conditions of cultural production, and as a result perhaps to remap the responsibilities which accompany them.

It is of absolute importance here to take into account the diverging local conditions that exist simultaneously in a state of permanent global entanglement and to acknowledge the challenging frictions that arise from the clash of the dissimilar politics, economics and social development, and of the production and insertion of transnational biennials within these contexts.

However, cultural policies in general, as well as the production of transnational biennials specifically, have to face this context and make use of it. Hereby the orientation is targeted towards a dual goal: firstly, the examination and definition of a contemporary identity, using forms of celebration, encounter, historicization, theorization and global contextualization; secondly, the strengthening of global visibility in order to position cities (often provincial or less developed ones) as cultural hubs, thereby attracting visitors, gaining prestige and contributing to the production of cultural values and knowledge.

[b]The vision of a glocal Gwangju[/b]

This is certainly the case for the Gwangju Biennale in South Korea. Here, culture as a political strategy emerged as a key role in order to compensate for the country’s lack of political and economic influence in Asia, in comparison with its powerful neighbors China and Japan, but also in order to establish a distinct identity for the city in order to emancipate itself from the capital, Seoul.

Okwui Enwezor, the artistic director of the 7th Gwangju Bienniale, clearly also sees political development and the founding of the event as closely related, when he says »The first steps toward claiming the political importance of open civil and cultural forums as indicators of a stable democratic sphere were made, with the support of the government in Seoul, by launching the first Gwangju Biennale in 1995.«1 Gwang Tae Park, in his function as the president of the Gwangju Biennale Foundation, claims that with regard to Enwezor’s 7th Biennale: »These efforts will no doubt cohere Gwangju’s position as a strategic signpost on the road to becoming the cultural hub-city of the global village and the cultural capital of Asia.«2

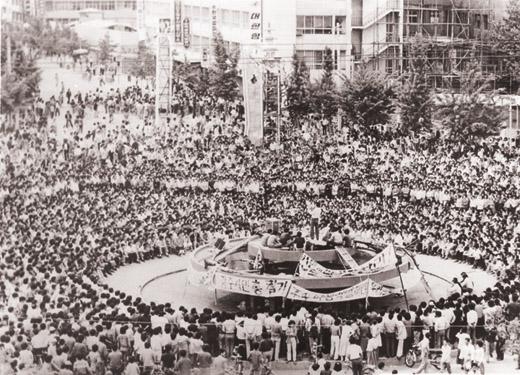

In addition, the Gwangju Biennale has clearly linked its founding myth to the now well-known May 18 uprising in 1980 that constitutes a key moment in the democratic formation of South Korea as an instance of self-empowerment, an experience of civic unity and liberation, and anchors the exhibition format in a genuine commitment to timely questions regarding civil society and the public sphere. »Beginning as a student protest in the southwestern city of Kwangju, the uprising escalated into an armed civilian struggle and was met by brutal acts of violence enacted by government troops. While the ten-day struggle ultimately ended in military suppression, its legacy and effects were of lasting significance. It was arguably the single most important event that shaped the political and social landscape of South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s.«3

The fact that South Korea was liberated from its Japanese occupancy by the U.S. in 1945 without Korea’s direct participation, and despite its persistent anticolonial struggles (which led to new Cold War dependencies), and was furthermore driven into a modernization process by a dictatorship, led to what Namhee Lee describes as a »history of failure« resulting in »the crisis of historical subjectivity«.4 This precondition explains why the May 18 uprising and its legacy in the minjung movement (meaning people’s movement, the democratic movement in South Korea) is given such a central position in the formation of identity.

In the legacy of the minjung movement, minjung art emerged, and in the 1980s and 1990s dominated artistic production in South Korea. The art of minjung is a politically and socially invested art practice that is aesthetically committed to Social Realism and is now often criticized for over-identification with nationalist nostalgia.

Against that background, the dedication to a »resolutely global, open-ended exhibition model, as a discursive site for both exhibition making and cultural debate« resonates as a desire to renew cultural identity, to define it as global rather than stagnate in provincial self-adulation. The aspiration to achieve neither predominantly national or Asian prestige, nor to emulate an ideal of the West (which paradoxically automatically reserves a second place at best), but to invest in the development of »globalism«5 as a strategy, is an intelligent move. A move that again gains weight with the knowledge that the southwest of the country, where Gwangju is located, has long been ignored in national political and economic matters, and has even been culturally stigmatized by Korea’s center of power as a »rebellious region«.6

In the execution of an event like the Gwangju Biennale it becomes clear that there is a sensitive distinction between Westernism and globalism, something that Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt captures in his notion of »Multiple Modernities«, which represents a view of the contemporary world and the history of modernity in itself that acknowledges the multiplicity of models. »One of the most important implications of the term multiple modernities is that modernity and Westernization are not identical; Western patterns of modernity are not the only »authentic« modernities, though they enjoy historical precedence and continue to be a basic reference point for others.«7

[b]»Spring« in Gwangju[/b]

The discourse around minjung and the quest for a timely aesthetic translation of the event resonates in various aspects in the 7th Gwangju Biennale. Besides a series of symposia in which the sociopolitical legacy of minjung was discussed in an interdisciplinary manner, and by an international cast, parts of the exhibition itself strive towards progressive contextualization. For example, booths of the traditional market daein were converted into exhibition spaces, aiming to provoke more discussion between different social classes; an aspiration which is deeply embedded in the events of Gwangju’s May 18, when educated elites fought for democratic freedom side by side with workers. In the following I want to discuss the particularly interesting and innovative curatorial project »Spring« by Claire Tancons in order to expose how the May 18 uprising and the history of minjung function as a specific reference, but how they avoid the danger of national sentimentality by building a global framework, which is characteristic for the Gwangju Biennale.

With »Spring«, Claire Tancons orchestrated a procession through the city of Gwangju, in which the traditions of the Caribbean Carnival, the practice of the New Orleans’ Creole funeral procession, and political demonstrations, were merged into a moving exhibition. A hybrid form was created which emphasized not only the interconnectedness of today’s world, but also unsheathed how tropes originating in different global cultural settings can inform each other, create discourse and produce new meaning in a new local condition.

Her strategy to treat carnival as an emancipatory lingua franca assumes that, unlike the spectacle, which according to Guy Debord is produced by an »excess of capital«, carnival is engendered by a lack of capital. She reinforces her argument by referring to the European tradition of the carnival, which vanished as an organ of the people, while in the Americas it thrived. Similarly the protest march, the demonstration, the riot, are all performed by a group of individuals who agitate as a voice for the underrepresented.

In terms of theoretical discourse, »Spring« revisits Guy Debord’s critique on capitalistic structures of modern societies, and defines carnival by its affinity with the grotesque, as »the spectacle of destruction, to destroy the spectacle«. It makes use of the Situationist goal »to wake up the spectator who has been drugged by spectacular images, through radical action in the form of the construction of situations«.8 In order to achieve this, Debord recommends the practice of »détournement«: a reappropriation of spectacular images and language to undermine the very structure of the spectacle. Claire Tancons attempts nothing less when she uses the carnival as the »anti-spectacular spectacle«.

[b]Structural Matters: Biennale versus Museum[/b]

Globalization has changed the economy of scale and also the pace of change in the art world. The flexibility of the biennale format works without doubt in favour of the idea of globalism, with its structures characterized by rhizomatic networks, temporary hubs, mobility of knowledge, and actors forming temporal communities and formats in flux.

The Biennale, as an agile hybrid combining entertainment and edification, functions as a platform for innovative artistic ideas; as an intellectual adventure that often breaks with its imperial taxonomies embodied by the national pavilion and increasingly presents itself as a transnational endeavor. Unlike the institution of the museum, the biennale was easily able to strip away the hegemony of a centre-periphery model.

Interestingly, the successful format of the international biennale gave rise to specific forms or formats of aesthetics that are not necessarily in the vein of the buyer’s taste, or reflected by the market organs of art fairs, commercial galleries and auction houses. With the new dimension of the exhibition, the scale of the works also grew; in the nineties »biennial fever«, the production of large-scale installations exploded, with a tendency to construct huge productions. Cinemascope projections appeared, small-format documentary was replaced by large-scale photographic imagery, and the formats of painting expanded to theatrical dimensions. This development can be interpreted as the result, and as evidence, of global mechanisms themselves, in which biennales are the showcases for emerging international artists who compete with many to gain access to limited resources, i.e. museum shows and commissions, representation by mainstream galleries and acquisitions by collectors. The factor scale therefore seems to be the strategy to gain crucial visibility. Okwui Enwezor similarly observes that »for many artists the anxiety of anonymity and failure in the face of stiff competition to be included in the exhibitions has meant that to be visible and noticed calls for the dramatic expansion of the spatial relationship of the objects and images produced to be commensurate with the global ambitions of the exhibitions themselves. In other words, mega-exhibitions require mega-objects«.9

While these circumstances certainly exist as a trend, it should also be mentioned that after almost two decades of an exploding exhibition boom, more and more voices call for more modest accounts and reflections. There is a renaissance of subtle artistic practices, including ephemeral gestures, intimate drawings, and research-based work, which are now to be encountered in biennales that work with timely matters regarding form and content. Such practices aspire neither to be instant eye-catching spectacle, nor to overwhelm the viewer in a spectacular totality.

Similarly, curators and exhibition producers began to address themselves to these concerns, and began to question the format of their own exhibitions. The 7th Gwangju Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor and his curatorial team, is certainly an excellent example of this critical practice, as is the 28th Sao Paulo Biennale, curated by Ivo Mesquita, which drastically reduced the number of artists and left a whole floor empty as a reflective space of encounter.

However, it would be dishonest to conceal the fact that in most transitional states professional museum structures, which are prepared to participate in the cultural discourse of modern and contemporary art, simply don’t exist. In an institutional landscape where long-established, prestigious collections compete for the few modern art pieces entering the market, and where financial resources lack the stability required for maintaining a serious museum, these young emerging players really have no choice but to focus on the contemporary moment. (»Young« in this context means relatively new entry into a global, cultural arena as nation-states, irrespective of their cultural heritage dating back thousands of years). Nevertheless, the format of the biennale, usually arising within an institutional framework which allows maximum flexibility in spatial terms, but more importantly flexibility in regards to the influx of people, ideas and the global networks that they bring, offers a way to engage in the production of cultural value and eventually to gain visibility.

[b]China and the spectacular[/b]

The conditions for museums described above are true even for China, where, according to Barbara Pollock, 1,200 museums are currently in the making. (Contrast this with 1977, one year after Mao’s death, where the country had around 300 or so museums, filled with political propaganda). Yet even today, most museums do not operate to Western standards. In practical terms this means that funding structures and legal status are often in limbo, bureaucracy and censorship create obstacles, and the staff lacks professional expertise.10 In China there is no legal framework for establishing a non-profit organization, which is somewhat ironic given that personal property did not officially exist either until recently, and also no tax benefits for making donations to cultural institutions. Therefore, art museums – both government-sponsored and private – must continually invent ways to raise money, often resorting to methods that might be considered illegal or unethical in the U.S. or Europe. Another key problem has been the absence of training programs for museum professionals such as art handlers, restorers, and curators, resulting in a lack of credibility, especially in respect of international co-productions.

In this climate inventive ways are found to circumvent official government cultural policy and the legal turbulence of a state in transition as it moves from a socialist past to become a capitalist super-power. A puzzling and provocative example is the artist and curator Lu Jie, a trickster figure of China’s art world with international ambitions and the founder of the Long March Foundation. He turned his multiplex independent art experiment, which used to swallow all his personal savings, into a profitable organization with an international résumé that is still involved in non-profit work. The Long March project (which is named after China’s revolutionary »Long March« from 1934-36, and is located in the now famous gallery district 798 in Beijing) provides a conceptual framework and now includes curatorial projects, a publishing house, a collection, a space for dialogue, a super-commercial gallery, consultancy services, a commissioning and production atelier, and training facilities for international young art professionals. However, he still defines his driving force, and the project’s mission, as »discussing ideals of revolutionary memory in a local context, and collaborating with participants from around the world to reinterpret historical consciousness and develop new ways of perceiving political, social, economical, and cultural realities«11.

Although biennials seem a hopeful platform to built prototypes of a counter public sphere, the interference of the state in cultural affairs remains a huge obstacle that doesn’t allow for the critical openness that would be necessary to produce a globally relevant debate. Art, political propaganda or differentiated vision, exist in dangerously close proximity in China, as is also the case for popular spectacle and a celebration of a new national as well as global identity.. The 7th Shanghai Biennale, located and organized by the Shanghai Art Museum, is one such example,12 facilitated respectively by its vice-director and chief curator of the biennale, Zhang Qing, who in turn appointed Julian Heynen and Henk Slager as international curators. This initial constellation already calls into question whether this event has the crucial attributes of the biennial format and again I see the event not only jeopardized by the fact that it is taking place exclusively in a museum setting, but also by its fixed personnel and the interference from officialdom. This is obviously problematic, as the biennale neither has the spatial freedom to choose its sites, nor does it allow the intellectual freedom that is necessary to develop a strong and original theoretical framework. The chosen theme and subject is »trans local motion«, which functions as a metaphor for the city’s floating population, its rapid growth in the last two decades and its constant influx of migrants, and is thus (like the Gwangju Biennale and others) enmeshed in the effects of globalization while concentrating on the context of the city of Shanghai. One of the three major chapters is dedicated to approximately 25 artists responding to the site of the People’s Square. Ironically, none of these works are located anywhere near the actual location, but are scattered around the first floor of the museum. The government managed to prevent a presentation on the People’s Square itself.

Much of the exhibited work is of inflated scale, trying to impress the viewer with spectacular dimensions, color or materiality. Little space is given to critical thought and reflection. And although the organizers of the biennale made an effort to introduce an increasing number of international artists (the proportion is approximately 50:50), the Shanghai Biennale remains, compared to the Gwangju Biennale with its explicit global aspirations, a local event; a very successful one though, considering the seemingly endless queue around the hopelessly over-crowded museum space.

As a point of departure in order to explain this phenomenon, it is important to understand the legacy of Chinese history, which tells a story of extreme insularity. Whereas South Korea’s history speaks of constant interpenetration with other nations, China has a past of deliberately reducing contact with foreign cultures, not least because of the sheer size of its empire, resulting in a focus that is traditionally directed inwards and that has never allowed much individual freedom. To imagine a biennial in Beijing that pays tribute to the Tiananmen massacre of 1989 following the example of Gwangju, with its celebration of minjung as national counter culture, is simply impossible in the unbroken political system of China.

The fact that the curators were not even mentioned in the introduction wall text, but instead the sponsors and the director general of Shanghai’s Administration of Culture, Radio, Film and TV, speaks for itself. Equally the overemphasis on the EXPO that will take place in Shanghai in 2010 makes this Biennale look like an image campaign for future sponsors, and does not lead to the thought that it could engage in a serious discourse on the effects of migration, urbanization and the state of the public sphere in China. Such a theme however would be very relevant for urban China, where in only three decades »generic cities«13 the size of New York or Paris have sprouted, with no recognizable center, no single identity and no history that could function as an aesthetic reference for appropriation, and which is challenging the work of urban planners and architects who aim to create an authentic environment for communities which for the most part have yet to develop.

[b]The biennials as the materialization of a concept of the world[/b]

Misgivings as to whethersite specificity is enough to create a successful urban environment are articulated by Rem Koolhaas when he says that an architect who intervenes in this environment must have »an opinion about what the world should be like«.14 This perhaps should be also a credo for curators, as they likewise build the image and imagination of a place.

A biennale should be an ambitious space to engage in frictions, to expose and bear tensions and to encounter crisis intellectually, and in that sense define the poles of the realm of spectacles. It would be problematic if it were instead to provide a framework for the total erasure of a critical momentum, an Olympia of the politics of visual representation, which, although being seductive for the masses, glosses over the fact that the claimed experience of modernity, of progression, of power, of demonstrative freedom, is only the freedom to consume.

In that sense the two biennials and the artwork presented set out the politics of representation at play, and thereby reveal the degrees of individualism, globalism and of course democratic freedom that are permitted in these transitional states.

1 Enwezor, Okwui: The Politics of the Spectacle; In: The 7th Gwangju Biennale – Annual Report, ed. Okwui Enwezor (Gwangju: Gwangju Biennale Foundation, 2008), p. 32

2 Gwang Tae Park, Greeting to The 7th Gwangju Biennale – Annual Report, ed. Okwui Enwezor (Gwangju: Gwangju Biennale Foundation, 2008)

3 Shin, Gi-Wook: Introduction to: Contentious Kwangju, the May 18 uprising in Korea’s past and present, ed. Gi-Wook Shin & Kyung Moon Hwang (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003)

4 Lee, Namhee: The Making of Minjung, Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007), p.2

5 Following the distinction between modernism and modernization, this term is introduced by Okwui Enwezor in his essay »Mega Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Form« to define the difference between globalization, meaning the processual negotiations of systems, institutions and corporations involved in worldwide political and economic power structures, in opposition to globalism, describing the position of actors concerned with modes of expression and cultural participation that emphasizes a state of interconnectedness, network character and multiplicity.

6 Yea, Sallie: Reinventing the Region: The Cultural Politics of Place in Kwangju City and South Cholla Province; In: Contentious Kwangju, the May 18 uprising in Korea’s past and present, ed. Gi-Wook Shin & Kyung Moon Hwang (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003)

7 Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah: Multiple Modernities; In: Comparative Civilizations and Multiple Modernities, a collection of essays by Shmuel Noah Eisenstadt (Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2003)

8 Simon Ford (1950): The Situationist International, A User’s Guide. (London: Black Dog, 2004)

9 Enwezor, Okwui: Mega Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Form; In: Other Cities, Other Worlds: Urban Imaginaries in a Globalizing Age (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009)

10 Pollack, Barbara: Making 1200 Museums Boom. Art News, March 2008

11 http://www.longmarchspace.org

12 http://en.shanghaibiennale.org/index.php

13 Ouroussoff, Nicolai: The New, New City; in: The New York Times, Architecture Issue, June 8, 2008

14 Ouroussoff, Nicolai: The New, New City; in: The New York Times, Architecture Issue, June 8, 2008