Issue 1/2009 - Net section

Unwanted positivism

On the term »post-medium condition« in the work of Rosalind Krauss

[b]»I am using the term ›technical support‹ here as a way of warding off the unwanted positivism of the term ›medium‹ which, in most readers’ minds, refers to the specific material support for a traditional aesthetic genre.« (Rosalind Krauss)[/b]

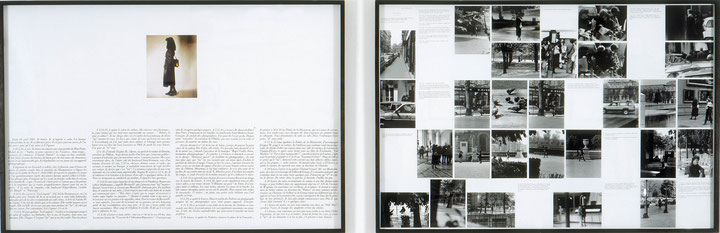

When US art historian Rosalind Krauss talks about the »post-medium condition«, she is referring, for example, to the artistic practice of Jeff Wall, whose light boxes pick up on the format of advertising posters and billboards used for commercial purposes in public space. Or to Sophie Calle’s »The Shadow« (1981), for which the artist engaged a private detective, who shadowed her and took photographs in the process – but had him in turn shadowed and photographed by a friend. Or she is referring to Dan Graham’s »Homes for America« (1966), which picks up on the format of journalistic photo reportage and was also published in a popular magazine. All these works share a conceptual attitude based on a reflective distance to the medium underpinning them. In this context the way in which they tease out a specificity of the medium is anything but an assertion of the purity of artistic expression. It is much more the case that they sketch out, to echo Krauss’ approach, a critique of the corrupt alliance between capitalist valorisation logic and the modernist ideal of the artistic sphere’s autonomy. In this type of performative positing of the medium as artistic practice, Krauss sees scope to nonetheless enter into a tangential relationship to the dominant value cycles of the cultural industry. This is however not so much with the intention of maintaining artistic autonomy but is much more in order to preserve a capacity to criticise. But what does the term »post-medium condition« mean as a reference system for art criticism?

There is a great deal to be said about Rosalind Krauss herself as a polemical, brilliant writer, co-founder of the journal »October«, and one of the most important Anglo-American art historians of her generation. The term »post-medium condition« plays a twofold role with reference to her writings. Firstly, it reveals the analytical attempt to take a concentrated dose of 30 years of critical revision of modernism and apply it to the artistic heritage of conceptual art. Secondly, it is an attempt within the context of art history to shape a concept without turning it into a monolithic structure. On the contrary: Krauss consciously opts to keep the notion non-specific in the course of several essays. Rather than being taken as a fixed constant, it is much more a changeable matrix, which can serve as a backdrop when addressing isolated observations – a method.

»At first I thought I could simply draw a line under the word medium, bury it like so much critical toxic waste, and walk away from it into a world of lexical freedom. ›Medium‹ seemed too contaminated, too ideologically, too dogmatically, too discursively loaded. I thought perhaps I could refer to Stanley Cavell’s concept of automatism.« These are the opening sentences of Krauss’ foreword to her seminal essay »A Voyage on the North Sea« – Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition« (1999).1 Of course her critique of the modernist notion of media cannot manage without the term »medium« either. Ultimately she is apparently interested in criticising the concept. The critical reception of this undertaking too, for example in the German-speaking world, is structured precisely in terms of the »medium«: for example, in his essay, entitled, like the thematic exhibition it addresses »Postmediale Kondition/ The Post-Medium Condition« (Neue Galerie Graz, 2005), Peter Weibel presents the argument that the technological progress seen in photography, video and digital media makes new art practices possible. He identifies a process of artistic re-appraisal in this, along with an enhanced status for the »historic media of sculpture and painting« in the post-modern era: »It is actually the post-medium computer, the universal machine, that makes it possible, apparently paradoxically but in reality entirely logically, to implement the wealth of the specificity of the [other, Comment by M. H.] media.«2 The »post-medium condition«, according to Weibel, refers to the media themselves. In adopting this position, he sketches out a positivist concept of media, which, whilst he does not situate artistic meaning in the medium itself, at least inextricably links its meaning to technological progress. When Weibel refers to the »post-medium condition«, he is referring primarily to the entrance of all media into the digital age.

This thorough investigation of the technological context of artistic production certainly falls within the ambit of the much more multi-layered argumentation put forward by Rosalind Krauss. What Weibel does not however take into account in his reflections is the trench warfare between various disciplines concerning art history in the English-speaking world. The critical reception there of a theory of the post-medium (like the theory itself) draws its legitimacy and sophistication directly from the New York context. However, in the process it is not just a progressive, positivist concept of the medium that has become the commonplace of »critical toxic waste«. For some time now there has been a well-established presumption of a constitutive Oedipal relationship between Krauss’ theory and the influential teaching of Clement Greenberg – renowned as one of the father figures of US modernism in the 20th century.3 The differing critical receptions of a theory of the post-medium appear mostly to be based on the assumption that their own demarcation of a historical age already contains the rudiments of their significance. The idea is too that a more profound meaning of the »post-medium condition« could be developed out of this. In fact, even in her late writings, Krauss spends an astonishing amount of time on establishing an unmistakable distance between her position and the dominant – or, as she calls it, »Greenbergised« – notion of the medium. However, the most strikingly specific aspect of Rosalind Krauss’ achievement is not so much her retrospective critique of the »classical media of sculpture and painting«, nor her oedipal critique of modernism’s positivist concept of the medium. Krauss’ theory develops its potential in a rhetoric of double negation, as a negativity of the medium that promises to escape the dictate of historical linearity: the »post-medium« nature of the artistic positions she describes is not directed at the technical specificity of the media used, in the sense of describing their positive effect, but instead describes the general »aggregate condition« of production, which is per se process-based. This »aggregate condition« can be understood as referring to a heterogeneous universe that also encompasses the discourses, institutions, physical support structures and their technological implications – in other words, both linguistic and non-linguistic elements: a machine-like arrangement. As a matter of fact that cannot be confused with a technological machine. It is not the medium that is the object of examination here but instead those factors that contribute to its individuation. This individuation is linked to an economic process in which recording and consumption are transported into production. The completed artistic work is merely evidence that this process of shaping has taken place, »just as a footprint on soft ground is evidence that someone has walked there«4. Searching for the difference separating the medium from itself, Krauss does not focus on the positivistic media specifics in her analysis but instead on a »differential specificity«. She does not necessarily tie this to photography, film or digital media but links it more generally to a shift in the experience of the medium as medium by understanding the negativity of both the cultural self-understanding and the availability of the technical/ technological dispositive – each medium must be understood as a perpetually repeatable set of conventions.

However, Rosalind Krauss is an art historian rather than a scholar of media theory. Her analysis also remains beholden to this approach and is in the classical sense a very intelligent art historical quest for clues – and not a meta-theory of media. That is precisely what keeps a concept with such an epic ring to it as »the post-medium« from drifting off into pretentiousness. Even if Krauss’ concept remains somewhat nebulous and even if the examples she selects thus seem somewhat arbitrary: provided that the concept is not understood as a mere demarcation of a historical period, it allows art historical practice to connect up with theories in the realm of social policy and biopolitics, without in the process seeking illustrations of these discourses in art works.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, Walter Neurath Memorial Lectures 31, London, Thames & Hudson 2000

2 Peter Weibel, Postmediale Kondition, http://www.neuegalerie.at/06/postmediale/konzept.html

3 C.f. on this point Daniel A. Siedell, Rosalind Krauss, David Carrier, and Philosophical Art Criticism, in: Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2004.

4 C.f. Rosalind Krauss, Sinn und Sinnlichkeit (1973), in: Gregor Stemmrich (ed.), Minimal Art. Eine kritische Retrospektive. Dresden 1998.