Artists and theorists have always been attracted by communities sharing a single (albeit abstract) online place. These used to be known as »online communities«, but nowadays this term sounds rather retro and outdated. The term »community« once referred to flocks of users gathering online to share one of their (possibly multiple) interests, but the business potential of these gatherings, and eventually their amateur/professional productions, was quickly exploited. Early examples of this data-gathering exploitation were the IMDB (Internet Movie Database) and the CDDB (Compact Disc Database), which both started as vast community-driven databases, open to all and built up by voluntary contributors, but ultimately acquired by corporations (Amazon and Sony respectively) and copyrighted. This trajectory seems to be a standard online business practice for corporations, but it is not so different from the gradual shift of the masses from collective mailing lists to web forums, and from web forums to social networks.

[b]Transparency in the offline world[/b]

Whereas collective mailing lists simply relied on (mostly) free distribution software, forums began forcing users to post their texts via a web interface, profiling each participant at some minimal level. Now social networks allow users to take the definitive step of giving away all of their personal data, exposing themselves in a global arena no longer restricted to a single community. Users are sending personal pieces of themselves (whatever is judged relevant, from intimate data, through to personal tastes) to small or medium-sized crowds of »friends«, with all the ambiguity that this can involuntarily generate. The pervasiveness of social networking platforms treads a thin line between our instinctive need to know everything, and the unstable borders of privacy. It’s a double-edged sword, because people usually want to know everything about others, but want to keep control of their own privacy, at least on some level. Thus the booming production of celebrity gossip news in the last decade seems to have had at least an influence on new levels of social transparency both virtual and real (witness here the Standard Hotel in Manhattan, where guests are virtually encouraged by the hotel’s staff to behave as exhibitionists at the rooms’ large windows facing onto a popular public park 1). This craving of attention from others is a common weakness, but it’s not a deadly virus.

[b]Antisocial attitudes[/b]

It’s worth noting that such practices, involving millions of people around the world, have also resulted in some degree of resistance. At various recent New York parties, guests have been requested not to blog, twitter/microblog or upload pictures of the event to Facebook2. The desperate need to have more »friends« (in Facebook slang), perennially aspiring to be the most popular person on the block, has supported the profit machine behind each social network, but at the same time has established fertile ground for a few artists’ practices. Hatebook3 for example, is a functioning ironic platform, a social exercise/experiment for people in the mood for releasing anger, tired of the spreading infection of superficial »friendship« (usually cynically used to acquire social visibility), whose members are ready to list their »enemies« and the things they hate. As the theorist Geoff Cox wrote: »without politics, our friendships are empty of meaning and our exchanges lead to nothing but the commodification of life itself.« Cox curated a seminal exhibition entitled »antisocial_notworking« for project.Arnolfini in Bristol. Going against the conformist social networking rules, he selected a series of artworks that deconstruct the kind of one-way social processes involved, going even further in questioning the dogma of the »network« as a democratic medium. On show was Wayne Clements’ »logo_wiki« (which identified military, corporate, and governmental editors of Wikipedia) as well as the »digital interventions« of Cory Arcangel. These included »Blue Tube«, a YouTube upload of a one second video, entirely black with only the YouTube corporation logo, which turns blue (the emptiness contrasts with the overwhelming abundance of the video sharing platform), and his early »Friendster Suicide«, a performance using Friendster, the ancestor of social networks, where Arcangel »suicides« his account (by disconnecting from each of his friends one by one) in a publicly netcast event.

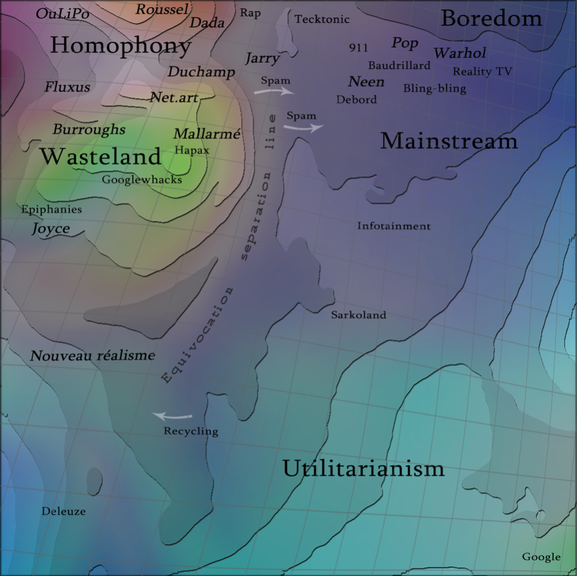

Another exhibition committed to this subject was »Tag ties and affective spies, a critical approach on the social media of our times« curated by Daphne Dragona at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens. In her introduction she wonders »What happens when taxonomies and structures become social?« Among other things, another myth is debunked here, that of the so-called folksonomy; the fuzzy collective construction of taxonomies through »tags«. It is achieved, for example, through the raw abstract approach of JODI, in »Winning Information«, whose eponymous del.icio.us account comprises only single letter tags which form words and colourful combinations of lines. Or through the sophisticated online linguistic cartographies (referring to language as a game) visualized by Christophe Bruno’s »Dadameter«. Concise language is the way of defining online entities at large, but also the best and most strategic way to promote them in the floating ocean of content that is the internet. So tags, or the shrewd use of short language, control the online destinies of different entities, including human ones.

[b]The pervasiveness of social networks[/b]

This leads back to the idea of continuous self-promotion. Is there a real commodification of relationships, as suggested by various social networks’ antagonists? Yes, for sure, even if it’s not pure commodification. It’s better defined as a bastardization of the beautiful and free spirit of human relationships, shamelessly mixing old friends, fresh self-promotion and the desperate need to build self-esteem in an overcrowded networked environment. This very instinctive social game is then mediated and dictated by different platform standards and rules. And the border of bastardizing and eventually commodifying personal relationships is easily crossed, inducing a mutual public »profiling« that has no end. The fragile digital identity is not only then scattered around the different identity-related entities, but also shaped around a production of elements that is both personally and randomly collectively generated. And herein lies the biggest potential: intertwining personal and public acts in an inextricable way, in order to build something that is no longer a »narrative« in a strict sense, but a new hybrid that embodies the definitive merging of real life and digital life, with no chance anymore of distinguishing between them. This should surely be a defining symbol of our quickly changing digital/real lives. But the game has only just begun.

1 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/09/fashion/09blogfree.html?_r=1

2 http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2009/08/25/us/AP-US-ODD-Exhibitionist-Hotel.html

3 http://www.hatebook.org