Issue 4/2009 - Wende Wiederkehr

The Lack of the Café »Els Quatre Gats«

New/post anarchism and a certain gap In new art radicalisms

[b]»The fact alone of bringing forth a beautiful work, in the full sovereignty of one’s spirit, constitutes an act of revolt and denies all social fictions […]. It seems to me, that good literature is an outstanding form of propaganda by deed […]. Whoever communicates to his brothers in suffering the secret splendour of his dreams acts upon the surrounding society like a solvent and makes of all those who understand him, often without their realization, outlaws and rebels.«[/b]

Pierre Quillard

[b]»It is not enough to make art.«[/b]

Guillermo Gomez-Pena

In 1993, Ayse Erkmen, a well-known Turkish contemporary artist, made a public art work – an iron sculpture known as the »Sculpture of Tünel«, in Istanbul’s historic Tünel Square. The sculpture was installed there after winning a competition organised by the City, and soon became a part of the public life in the square. And 12 years later, in 2005, another artist, Kemal Önsoy, covered it with styrofoam, as a part of a »public art« exhibition (Istanbul Pedestrian Exhibition 2). So Önsoy had made an artwork (entitled »Mutual Aid«, as in the title of Kropotkin’s great book) on another artwork, as a direct intervention in public life in the square. Unfortunately, one night while Önsoy’s work was being exhibited, someone (street kids, it was said) set light to the styofoam, which consequently lead to the burning down of the whole Erkmen’s iron sculpture/artwork as well. The event made the work a news story in newspapers and on TV channels. After some time, the original artwork was remade — Kemal Önsoy’s work was never remade, as you can guess — and Erkmen’s work became a part of public life in Tünel Square once again, and again was full of life, with children playing on it, etc.

Then, on the 26th of April 2009, there was a demonstration in the Tünel Square. Activists were holding a sort of rehearsal for the coming May Day celebrations, chanting slogans as a part of the demonstration, which ended with a clash with the police. Then some activists climbed Erkmen’s sculpture and hung a black flag on top of it. It was quite good to see art and politics meeting on such an occasion. That night, activists circulated a news sheet about the demonstration, giving their own perspective. Included in this text they described how they »hung a black flag on that iron column in the Tünel Square«! That iron column in the Tünel Square?! It was so obvious that they did not think of it as an artwork, just an iron column in the Square!

I wouldn’t read this event as a proof showing how ignorant or indifferent activists are, but would rather read this as a key moment revealing the gap within art radicalisms today; I use it here as a valuable anecdote illustrating the distance between activist circles and contemporary artists – even when both parties are »into« public art, social transformation, social »intervention« etc.

[b]New activism and the anti-globalisation protests[/b]

The new in art, especially the artistic-political movements for the public, has little in common with the new political activism, but these similarities are neither particularly clear nor fruitful. On paper, defining the new activism would position it close to many new public art acts, but in practice this is not the case. There is no organic communication between new activists and new political movements in art, and there exists a real aloofness between the new activist tendencies, principles, and organisational attitudes after Seattle (the anti-globalisation left) and the new political artistic gestures. Organisational principles/practices and theories of the post-Seattle activism have much in common with most of the political movements in contemporary art that we see today – but without a productive artistic or political dialogue.

So because of the distance between the activist art works and activists themselves, there is a certain »gap« in the new art radicalisms, between the »natural audience« of a renewed art position and the practitioners of these art works. But before examining this gap, we should look more closely at the »new« in this activism.

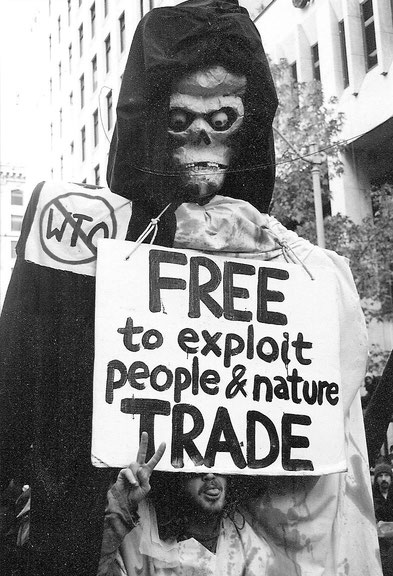

Anarchism is widely accepted as »the« movement behind the main organisational principles of the radical social movements in 2000s. The rise of the »anti-globalisation« movement has been linked to a general resurgence of anarchism. It was colourful, energetic, creative, effective and »new«. And credit for most of the creative energy behind it went to anarchism1. Anarchism appeared to be reclaiming its name as a political philosophy and movement from the violent connotations of chaos and violence. Although the mainstream media strategy of focusing on the »Black Bloc« aimed simply to reproduce this image and consequently failed to support the movement2, this approach on the other hand helped to attract the attention of political thinkers and activists trying to understand what all the fuss was about. This, in turn, resulted in more scholarly and political works on anarchism and the new »movement«.

We generally use quotation marks when referring to the »anti-globalisation movement« because there is of course no one single author of the movement who would give it an official name. Besides, the activists, groups and initiatives involved did not reach a consensus on using the same term. It has been referred to as the Global Justice Movement, the Movement of Movements, the Movement, the Alter-Globalisation Movement, Radical Social Change Movements, Contemporary Radical Activism, the Anti-Capitalist Movement, the Anti-Corporate Movement, the Global Anti-Capitalist Protest Movement, the Counter-Globalisation Movement, the Anti-Corporate-Globalisation Movement, the Grassroots Globalisation Movement and more. The discontent most of the activists felt with the term »anti-globalisation« arises from the fact that it was coined by the »enemy« (a »Wall Street« term, coined by the corporate media) in order to label the activists as outmoded, blind, self-referential youngsters spitting into the wind (unstoppable globalisation) for no valid reason other than the joy of damaging property. Activists also protested against the term because they were not opposed to the globalisation per se.3

On the other hand, proudly using once pejorative labels has historical roots in the politics of the left. As Kropotkin points out, the term anarchism itself is a good example of this tradition. Kropotkin had to stand considerable criticism for using the term to describe a political and philosophical movement, when, in everyday language it meant disorder and chaos. In his short essay »L’Ordre« (On Order), first published on October 1st 1881 in »Le Révolté«, Kropotkin embraced the term »anarchy« and recognised the rebellious legacy in it. He made reference to the »beggars« of Brabant who didn’t make up their name (referring to the Dutch Sea beggars, Dutch rebels against the Spanish regime in the late sixteenth century) and the »Sans-culottes« of 1793 referring to the French revolution. »It was the enemies of the popular revolution who coined this name; but it too summed up a whole idea – that of the rebellion of the people, dressed in rage, tired of poverty, opposed to all those royalists, the so-called patriots and Jacobins, the well-dressed and the smart, those who, despite their pompous speeches and the homage paid to them by bourgeois historians, were the real enemies of the people, profoundly despising them for their poverty, for their libertarian and egalitarian spirit, and for their revolutionary enthusiasm.« Borrowing the same spirit, we can use the term in a way that globalisation only implies global capitalism or global neo-liberalism.

The relationship between anarchism and the anti-globalisation movement has been mutual; on the one hand, anarchism was the defining orientation of prominent activist networks, and it was the »principal point of reference for radical social change movements«.4 Thus anarchism provided the established tools and organisational principles. And on the other hand, the »anarchistic« rise of anti-globalisation, the popularity it gained and, more realistically, the major role it played in the first years of 21st century radical politics through open usage of anarchistic notions and the massive numbers of anarchist activists within the movement, was »widely regarded as a sign of anarchism’s revival«.5 It was even stated that »the past ten years have seen the full-blown revival of anarchism, as a global social movement and coherent set of political discourses, on a scale and to levels of unity and diversity unseen since the 1930s.«6 A tradition that was »hitherto mostly dismissed« now required a respectful engagement.7 Simply put, the anti-globalisation movement brought anarchism back to the table. The anti-globalisation movement challenged the dominant position of Marxism as »the« left political philosophy and movement even more than the collapse of USSR. There were anarchist forms of resistance and organisation everywhere: »from anti-capitalist social centres and eco-feminist communities to raucous street parties and blockades of international summits, anarchist forms of resistance and organisation have been at the heart of the ›alternative globalisation‹ movement«.8 Anarchism was »the heart of the movement«, »its soul; the source of most of what’s new and hopeful about it.«9 »The model for the kind of political and social autonomy that the anti-capitalist movement aspires to is an anarchist one, and the soul of the anti-capitalist movement is anarchist; its non-authoritarian make-up, its disavowal of traditional parties of the left, and its commitment to direct action are firmly in the spirit of libertarian socialism.10

[b]The new anarchists[/b]

So anarchists themselves, and more importantly anarchist principles, first served as the organising principle of the new emerging anti-globalisation movement. And in turn, the emergent movement served both as a global platform of testing anarchist principles in the new conditions of world politics, and as an Archimedes’ lever that largely displaced Marxism and brought anarchism to the attention of activists and academics worldwide – making anarchism widely recognised as a consequence.11 It led to an »almost unparalleled opportunity to extend the influence of their (anarchists’) ideas«12 and on the theoretical level, it did not only give rise to anarchist-influenced activist research, but also fostered contemporary anarchist theory. It was even a new opportunity for forming a new base for an anarchistic social theory. We witnessed growing numbers of scholarly publications and events on anarchism, but more interestingly anarchism was used as a source of radical thought much more frequently and intensively than before.13

But this empowered, updated contemporary anarchism was not a reincarnation of 19th century anarchism returning from the days of the First International, or the 1934 Spanish anarchist revolution. Rather, this was something »new«. There was a consensus that this was an anarchism re-emerging; it was, at least, »a kind of anarchism«. But what kind?

The term became widely accepted soon after David Graeber’s article »The New Anarchists« was published in one of the most prominent Marxist oriented journals, New Left Review14. For example, Sean Sheehan began his introductory book Anarchism with a chapter entitled »Global Anarchism / The New Anarchism.« A book which was supposed to cover anarchism as a political philosophy and movement, began with detailed accounts of the »Battle of Seattle«15 – the legendary protest against the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in November 1999; »five days that shook the world« as the title of one collection says16. Of course, when the term was used in activist circles, it was not necessarily a reference to David Graeber’s use of the term in his New Left Review article. The expression »new anarchists« enjoyed a »wider usage within contemporary anarchist scenes«.17

The key »new« element of the »new anarchism« was basically its range of references. All the anarchistic principles employed were defined by actual experiences. There was almost no intention to describe the movement as an application of an anarchist theory (which is itself a fundamentally anarchistic attitude). For Graeber, the anti-globalisation movement is »about creating new forms of organization. It is not lacking in ideology. Those new forms of organization are its ideology. It is about creating and enacting horizontal networks instead of top-down structures like states, parties or corporations; networks based on principles of decentralized, non-hierarchical consensus democracy.«18 Nevertheless, Uri Gordon offers an analysis of »present-day anarchist ideology from a movement-driven approach«.19 But it is no surprise that at the ideological core of contemporary anarchism20 he finds an »open-ended, experimental approach to revolutionary visions and strategies.«21 Methods of protest and symbolic gestures of the anti-capitalist movement are interpreted as an »anarchist-inspired opposition to neo-liberalism« which was sometimes combined with pragmatism.22

This open-endedness gave »new anarchism« an additional elusiveness which later led to its position as forcefully split from »classical anarchism«. »Classical anarchism« is another controversial term; positioned as a fixed ideology represented through the work of a select band of 19th century anarchist writers, where even those writers’ thoughts are reduced to certain clusters of ideas that only helps to confirm prejudices about the »classical anarchists«. The discussions surrounding the ideas concerning the »new« versus »classical« anarchism were even understood as a part of the »conceptual and material evidence« of »a paradigm shift within anarchism«.23

In many cases, this quickly turned into a debate about »post-« versus »classical« anarchism. Mostly, this contemporary need to re-position anarchism fostered all the new studies and discussions on postanarchism. Postanarchism was largely understood in the framework of »new«/»post-« versus »classical« anarchism. There was a close fit between the »new« anarchism’s system of coordination and the way »postanarchism« refers to poststructuralism on how to build a left that embodies its own values. A left whose values are immanent is a left that thrives without authority and repression, and rids itself of both inward- and outward-directed ressentiment.24

Postanarchism carried a direct influence of the contemporary philosophy after the 1960s, to debates around classical anarchism vs. new anarchism. Postanarchism’s relevance to the anti-globalisation movements is confirmed by two of the most prominent writers associated with postanarchism in the English speaking world - Saul Newman and Todd May – who both explicitly affirmed this relationship. During interviews conducted by the Turkish postanarchist magazine »Siyahi«, they both agreed that »post-Seattle anti-globalisation movements« »absolutely« and »certainly« have comparable motives with the poststructuralist anarchy/postanarchism. May lists »similar ideas informing both movements« as »irreducible struggles, local politics and alliances, an ethical orientation, a resistance to essentialist thinking«.25 Newman goes further, and while emphasising the parallel motives between the anti-globalisation movement and postanarchism, he also draws a definition of postanarchism: »Postanarchism is a political logic that seeks to combine the egalitarian and emancipative aspects of classical anarchism with an acknowledgement that radical political struggles today are contingent, pluralistic, open to different identities and perspectives, and are over different issues – not just economic ones.«26

Here Newman defines postanarchism as an attempt to combine insights from classical anarchism with new anarchist epistemologies. Yet on the other hand it is possible to argue that postanarchism is actually the attempt to create the theoretical equivalent of anti-globalisation movements. The rise of postanarchism debate is directly linked to the post-Seattle spirit of the anti-globalisation movements. Theoretical attempts to marry poststructuralism/postmodernism and anarchism in various ways were suddenly embraced by activists or activism-oriented scholars worldwide.

[b]The »genealogy« of postanarchism[/b]

The turning of postanarchism into an »–ism« – a current among the family of various anarchisms – owes much to the web site and email list created by Jason Adams. Adams started the email list as a Yahoo group on 9th October 2002; he made a web page on February 2003, from which the Spoon Collective became the next mailing list provider of the email group. The tone of emails back then reflects a certain excitement.27 Adams himself was an activist-academician who had spent the entire year organising the WTO protests in Seattle, where he was living at the time. He also played an important role by organising the »N30 International Day of Action Committee«, which set up the primary web site and international email listserv which was used to promote coordinated action against the WTO worldwide. The WTO protests were the real turning point at which he began to move in the theoretical direction of »postanarchism«. In his essay »Postanarchism in a Nutshell«28, he gives a short description of postanarchism and outlines its contents. Adams takes poststructuralism as a radically anti-authoritarian theory that emerged from the anarchistic movements of May 1968, developed over the past three decades, and finally, in the form of »postanarchism«, came back to inform and extend the theory and practice of one of its primary roots (anarchism). This positioning of poststructuralism is not as peripheral as it would first seem.

For example, Julian Bourg sees an ethical movement as the legacy of May 1968, depicting the time as the »implicit ethics of liberation«. He sees a continuity of ethical debate, that begins with May ‘68 and continues with the »French theory« in the 1970s.29

The emphasis on an ethics of liberation has always been known as anarchists’ primary concern during revolutionary/political action and theory. That’s why prefigurative politics have been one of the touchstones of anarchism. According to Bourg, the activists of May 1968 were essentially declaring that freedom is not free enough, equality is not equitable enough and imagination is not imaginative enough.30

The connection Bourg suggests has to do with the historical roots of ethical concerns within the »French thought« that goes back to social movements and activism of May 1968. Bourg argues that Deleuze-Guattari’s »Anti-Oedipus« brought to the fore the ethical intransigence of the antinomian spirit of 1968 and concretised a broader cultural ambience of post-1968 antinomianism.31

When Bourg lists the »values of the May 1968 movement«, anyone familiar with anti-globalisation movements, anarchism and French theory (and political contemporary art today) would easily see parallels: »imagination, human interest, communication, conviviality, expression, enjoyment, freedom, spontaneity, solidarity, de-alienation, free speach, dialogue, non-utility, utopianism, dreams, fantasies, community, association, antiauthoritarianism, self-management, direct democracy, equality, self-representation, fraternity and self-defence.«32

Douglas Kellner also sees the connection as very clear: »Thus, in place of the revolutionary rupture in the historical continuum that 1968 had tried to produce, nascent postmodern theory in France postulated an epochal coupure, a break with modern politics and modernity, accompanied by models of new postmodern theory and politics. Hence, the postmodern movement in France in the 1970s is intimately connected with the experiences of May 1968.33

Kellner’s interpretation of the spread of the ideas of May 1968 into »postmodern theory«, Bourg’s emphasis on poststructuralist works as concretised forms of the spirit of 1968 and Adams’s way of locating postanarchism as poststructuralism finally coming back to its roots (i.e. the spirit of May 1968 found in contemporary anti-capitalist movements which are equally anti-authoritarian); all show a different »family tree« for postanarchism, than perhaps a version that Todd May might offer. Instead of taking poststructuralism as a separate body of thought that stands apart from activism in general, and from anarchism specifically, as something that can be or should be rethought in combination with activism/anarchism, we see in Adams’ approach a historical tracing of poststructuralism that follows the context in which it was created; the personal, and thus political, backgrounds depicting poststructuralism as a continuation and theoretical equivalent of the anarchistic activism since the 1960s. We can roughly define the main periods of anarchism since the nineteenth century thus: the first period ends with the defeat in Spain in 1939, the second period is marked by the 1960s, and the third period runs in parallel to the anti-globalization movements.

[b]Art radicalisms[/b]

If on the other hand, for example, we remember the story of punk as told by Greil Marcus in his »Lipstick Traces, A Secret History of the 20th Century«,34 the radical approach in punk can easily be rooted in Lettrism and Situationism. Marcus also pictures the obvious continuation of the Dadaist character in both Lettrism and Situationism, and subsequently how all had straightforwardly influenced not only punk but also student revolt of May 68 (which would influence the poststructuralist thought). However, Marcus focuses only on Dada as an earlier radicalism of the modernist art movement.

But if we continue to follow these intermingling family trees, we will see that early political radicalism of early last century had a direct influence on modernist radicalism, from neo-impressionism to cubism, futurism, constructivism, dada etc. And this political radicalism tended towards anarchism much more than Marxism, in a wide range of artists, from Malevich to Picasso.35

Radical artists contributed to anarchist magazines, had anarchist friends with whom they chatted and drank in cafés like »Els Quatre Gats« (»The Four Cats«) in Barcelona, and they were realising projects together. Meeting points, and nodes such as »Els Quatre Gats« were crucial; these anarchist art movements had an influence on world-wide radicalism, and weren’t just limited to Western Europe.

Later, updating avant-gardism for the mid 20th century, Lettrism and Situationism carried the spirit of the libertarian left skills into May ‘68, by always employing radical art views/practices hand-in-hand with radical political views/practices. Thus, we can trace the genealogy of May ‘68 to see how it was tied to anarchistic activism in the 1900s along an artistic avant-garde thread. So May ‘68 had a direct influence on poststructuralism, which in turn had a direct influence on current activisms, not only through postanarchism but also by dominating the new epistemologies which led to a new politics of anarchism. Same poststructuralist theories also influenced the epistemologies behind the contemporary art radicalisms, from relational aesthetics to notions of understanding artists’ positions or direct references to theory. But there is admittedly a problem concerning the ability of memory. Radicalism in art does not feel much indebted to activism of any era, not only to early modernists, and activism today does not feel any debt to the role radical art played in developing and conveying the attitude of radicalism through until today. You may ask: is it really important? Does it matter if they don’t care about their roots?

Certainly it wouldn’t be a problem if they continued the relationship as it would be needed today. The problem is: the radicalism of the new genre of public art, and other contemporary art forms, is simply flowing away today. To pursue the political critique and intervention, which they have initiated, they need a radical political audience – an audience with a culture of participatory intervention. The gap in the political radicalism of the art is created simply by the absence of this audience. The new political and artistic connections between the new artistic political movements do not arise in the same cafés, coffee shops, such as the »Els Quatre Gats«.

Today we frequently face art as social critique, as an instrument of change, as Suzi Gablik describes it: »There is a distinct shift in the locus of creativity from the autonomous, self-contained individual, towards a new kind of dialogical structure that is often not the product of a single individual but is the result of a collaborative and interdependent process.«36

When Angelika Nollert, in the catalogue of the 2005 exhibition »Collective Creativity« at the Kunsthalle Fridericianum, calls attention to how the idea of collective creativity (as opposed to individual creativity, »the myth of the unique genius«) has been developed in avant-garde movements, from Surrealism to Fluxus and Viennese Actionism, we should keep in mind that the collective sensibility was established by the anarchist political activism at a very early stage of these series of movements.

The literature on the current activism exhibits defining principles of the movement in a highly »relational«, horizontal, grassroots-based, anti-nationalist, anti-militarist and anti-hierarchical way, that has much in common with current trends in the art scene – and yet it looks as if it deprives us of the need for interdisciplinary collective creativity, which is best blurred and revealed in daily life, as we drink together in a dim café.

1 Graeber, D. (2002) »The New Anarchists«, New Left Review, 13.

2 This approach also met with great approval by governments, as seen in Tony Blair’s depiction of the movement as an »anarchists’ travelling circus« that »goes from summit to summit with the sole purpose of causing as much mayhem as possible.« See »Blair: Anarchists will not stop us«, BBC News, 16.06.2001. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/1392004.stm .

3 J. Conway, Civil Resistance And The »Diversity Of Tactics« in The Anti-Globalization Movement: Problems Of Violence, Silence, And Solidarity In Activist Politics, in: Osgoode Hall Law Journal, 2003, 41: 2 & 3, pp 505–30.

4 U. Gordon, Anarchism Reloaded, in: Journal of Political Ideologies, 12, 2007, p.29.

5 R. Kinna, Anarchism: A beginner’s guide. Oxford 2005, p.67.

6 Gordon, Anarchism Reloaded p.29.

7 Graeber, The New Anarchists, p.1.

8 Gordon, Anarchism Reloaded p.29.

9 Graeber, The New Anarchists, p..1.

10 S. Sheehan, Anarchism. London 2003, p.12.

11 Teoman Gee, an anarchist activist and writer from the USA, openly equates this rise of prestige for anarchists with the rise of anti-globalisation movements. »[During] the first ten years of my involvement in anarchist politics (from 1989 to 1999) being an anarchist was an oddity, and the scene pretty much resembled a social ghetto that was usually despised and subjected to ridicule, even amongst non-anarchist political radicals. At best, we were seen as incurable idealists, chasing dreams of a just society made for fairytales much rather than the real world […]. One often didn’t dare declare oneself an anarchist in radical networks geared towards single-issue political activism, just to avoid the danger of not being taken seriously. […] what does seem essential is to recall the isolated and disregarded socio-political space we found ourselves in as anarchists for almost all of the 1980s and 1990s […]. This has changed drastically since November 1999, especially in the US. It’s common now to read about anarchists in the media, to introduce oneself as an anarchist, to refer to your neighbour as an anarchist. Anarchists finally seem to have recognition.« (»New Anarchism: Some Thoughts«, Teoman Gee, Alpine Anarchist Productions. 2003, pp. 5-6).

12 Kinna, Anarchism: A beginner’s guide, p.155

13 J. Bowen, J. Purkis, Changing Anarchism: Anarchist Theory and Practice in a Global Age. Manchester 2004; J. Cohn, Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation: Hermeneutics, Aesthetics, Politics. Selingsgrove 2006; J. Moore, J. Purkis, S. Sunshine, I Am Not A Man, I Am Dynamite!: Friedrich Nietzsche and the Anarchist Tradition. New York 2004; R. Day, Gramsci is Dead: Anarchist Currents in the Newest Social Movements. London/Ann Arbor, Pluto 2005; T. Kissack, Free Comrades: Anarchism and Homosexuality in the United States 1895–1917. Edinburgh 2008; B. Anderson, Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination. London/New York 2005; A. Antliff, Anarchy and Art: From the Paris Commune to the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Vancouver 2007; R. Amster, Contemporary Anarchist Studies. London/New York 2009; N. Jun, New Perspectives on Anarchism. Lanham 2009.

14 On the other hand, Graeber rejects the »honour« of being the person who first coined the term. He even denies that he has ever used it: »I never used the expression »new anarchist« myself. It’s in the title of the New Left Review piece, but the magazine wrote the title, not the author. I didn’t object to it but I would never use it as a title in that way. Insofar as I’ve ever consciously designated myself a particular type of anarchist it’s with a »small a« – which is above all the kind that doesn’t go in for particular sub-identities.« (personal email 17.11 2007) Ironically he is sometimes introduced as »anthropologist, »new-anarchist« theorist and activist David Graeber« ( http://www.glovesoff.org/features/gjamerica_4.html ). Actually, the first version of Graeber’s article was first published as »The Globalization Movement: Some Points of Clarification« in Items & Issues (vol. 2, no. 3, fall 2001), the newsletter of the Social Science Research Council – http://publications.ssrc.org/items/ItemsWinerter20012.3-4.pdf . The article displayed an early and strong attempt to conceptualize the ideology of the new movement as a set of anarchistic organisational principles. It was so »new« that as I was trying to translate the piece into Turkish (which was later published in Varlik, December 2001, SAYI 1131, p.45–49) I couldn’t understand some key terms and asked the author for their meanings. The terms were: break-outs, fishbowls, blocking concerns, vibes-watchers, facilitation tools and spokescouncils. A collection of technical terms used within the movement for direct democracy were mentioned by Graeber himself on purpose simply to show that such a technical language exists. Detailed explanations of those terms can be found in the longer New Left Review version of the article.

15 Sheehan, S. (2003) Anarchism (London: Reaktion).

16 This reference to John Reed’s »Ten Days That Shook the World« was actually more important than a catch phrase. It implied a kind of comparison: if Bolshevik revolution was the revolution of the last century, of Marxists, of the past, then the »Battle of Seattle« was the revolution of this coming century, of future anarchists. On the other hand, the phrase was used for another uprising a few years before – after the Los Angeles riots of 1992. »Three Days That Shook the New World Order« was a pamphlet published by the Chicago Surrealist Group in 1992 (It can still be found on: http://zinelibrary.info/files/320Days.pdf ). The Chicago Surrealist Group, as their name would imply, is an art theory group focusing on surrealism with an anarchist background, with its origins dating back to 1960s. Believing that this well written text has also envisaged some political and cultural dimensions of postanarchism, we were providing direct links to it, on the web pages made by our first postanarchist collective in Istanbul, called the Karasin Anarchist Collective (1996–1998). Of course, if we compare Los Angeles 1992 with the »Battle of Seattle«, one of the first issues that would draw our focus would be the race factor. For an early discussion of the race issues in Seattle, see »Where was the Colour in Seattle?: Looking for reasons why the Great Battle was so white«, by Elizabeth Betita Martinez (see http://colours.mahost.org/articles/martinez.html ). Additionally, George Katsiaficas argued that the representation of the Battle of Seattle is also excludes non-western precursors of the protests (The Battle of Seattle: Debating Corporate Globalisation and the WTO. New York 2004). This detail is also important from my perspective on the history-writing processes of anarchism in general, because even in this contemporary horizontal activism and global protest movement, we still have issues about representing the history of an anarchist event, which were criticised in detail by Katsiaficas in his article »Seattle Was not the Beginning«. (included in the Battle of Seattle).

17 T. Gee, New Anarchism: Some Thoughts. Alpine Anarchist Productions 2003, p.3.

18 Graeber, The New Anarchists, p.70.

19 Gordon, Anarchism Reloaded, p.29.

20 Tadzio Müller goes further, claiming that »if anarchism is anything today, then it is not a set of dogmas and principles, but a set of practices and actions within which certain principles manifest themselves […]. Anarchism is not primarily about what is written but what is done.« (Empowering Anarchy. Power, Hegemony, and Anarchist Strategy, in: Anarchist Studies, 2003, 11:2, p.27). So here Müller first denies the superior position of theory over practice, and proposes the primacy of practice/experience.

21 Gordon, Anarchism Reloaded, p.29.

22 Sheehan, Anarchism, p.16.

23 Bowen, Purkis, Changing Anarchism, p.5.

24 K.M. Kang, Agonistic Democracy, the Decentred »I« of the 1990s, Ph.D.Thesis, University of Sydney, Australia, 2005, S. 90.

25 Interview with May, »Siyahi«, 2004, no:1. Also in the interview with Rebecca deWitt, May says: »As an activist, I find myself in accordance with the recent demonstrations intended to eliminate the WTO.« (May 2000)

26 Interview with Saul Newman by Sureyyya Evren, Kursad Kiziltug, Erden Kosova, in: Siyahi, November–December 2004, Nr. 1, Istanbul, pp. 4–11.

27 See the full archive of the postanarchism email list on the Spoon Collective here: http://www.driftline.org/cgi-bin/archive/archive.cgi?list=spoon-archives/postanarchism.archive . But the tone of excitement can be better traced in Yahoo group archives, open to members only: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/postanarchism .

28 Adams’ much referred-to essay was also published under the title »Postanarchism in a Bombshell« in Aporia journal. See http://aporiajournal.tripod.com/postanarchism.htm .

29 J. Bourg, From Revolution to Ethics: May 1968 and Contemporary French Thought. Montreal 2007, p.7.

»The ethics of liberation accordingly emerged in those social spaces where class-based revolutionary – and even reformist – politics were judged insufficient. For example, the popular statement ›the personal is political‹ was in essence eminently ethical; 1968 itself implied an ethics, the ethics of liberation, with both critical and affirmative sides.« Bourg, 2007, p. 6.

30 Ibid., p.7.

31 Ibid, p.106 f.

32 Ibid, p.7.

33 »The passionate intensity and spirit of critique in many versions of French postmodern theory is a continuation of the spirit of 1968 [...]. Indeeed, Baudrillard, Lyotard, Virilio, Derrida, Castoriadis, Foucault, Deleuze, Guattari and other French theorists associated with postmodern theory were all participants in the events of May 1968. They shared its revolutionary elan and radical aspirations, and they attempted to develop new modes of radical thought that continued the radicalism of the 1960s in a new.«

D. Kellner, When Poetry Ruled the Streets: The French May Events of 1968, Preface. New York 2001, p. xviii.

34 Marcus, G. Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century (Picador, 1997).

35 C. Cooke, Sources of a Radical Mission in the Early Soviet Mission, Alexei Gan and the Moscow Anarchists in Architecture and Revolution, Contemporary Perspective on Central and Eastern Europe, ed. by Neil Leach. London Routledge 1999; R. Roslak, Neo-Impressionism and Anarchism in Fin-de-Siècle France: Painting, Politics and Landscape. Ashgate 2007; P. Leighten, Re-ordering the Universe: Picasso and Anarchism, 1897–1914. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press 1989.

36 S. Lacy, Mapping the Terrain, New Genre Public Art. Seattle 1995, p.76.