On AT&T Plaza in Chicago\\\'s Millennium Park stands a giant stainless steel sculpture in the shape of an indented ellipsoid, 66 feet long, 33 feet high, weighing 110 tons and glistening in the sun like a drop of liquid mercury. Entitled »Cloud Gate« by the British artist Anish Kapoor, and nicknamed »the Bean« by locals, it cost 11.5 million dollars and immediately became what it was always intended to be, an urban attraction photographed by endless tourists, the world-renowned symbol of a creative city. Stand below the arching mass of the sculpture and gaze upwards at the omphalos or navel: your body multiplies into drunken curves, improbably fat and impossibly thin, like in a funhouse mirror. Look back at the sculpture from a few steps away: your diminutive image is crowned by a ring of skyscrapers, their outlines etched against a blue horizon.

Returning home from a recent trip to Detroit and a string of other half-devastated cities, I realized viscerally what I knew intellectually: that Chicago is the incomparable winner of the region, the Midwestern capital of the global economy. It\\\'s the city that pioneered both commodity and financial futures, and after a recent round of mergers it is now home to the world\\\'s largest futures and options network, the GLOBEX trading platform, run by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group (the »Merc«). Elite knowledge workers are making tremendous amounts of money in this city. Yet our neighborhood just a few miles from the lakeshore is full of boarded-up houses and lives that have been foreclosed by the crisis. Twenty percent of the inhabitants have fallen beneath the poverty line and a quarter of the population has no health insurance. The municipal housing projects have been destroyed for private development, and over thirty percent of the high school students will not graduate.1 On a sunny day you can see the bright blue sky through the rust-eaten girders of the elevated transport system.

This essay describes the workings – and indeed, the work force – of a variety of capitalism that has spread outwards from its Anglo-American core to reshape the entire planet. At the center of contemporary capitalism is a set of financial instruments called derivatives, and a group of people called traders. The text draws links between their highly abstract formulas and the aesthetics of lived experience. It begins not with the azurean blue, but with the curve of a dark horizon.

Unstable Constellations

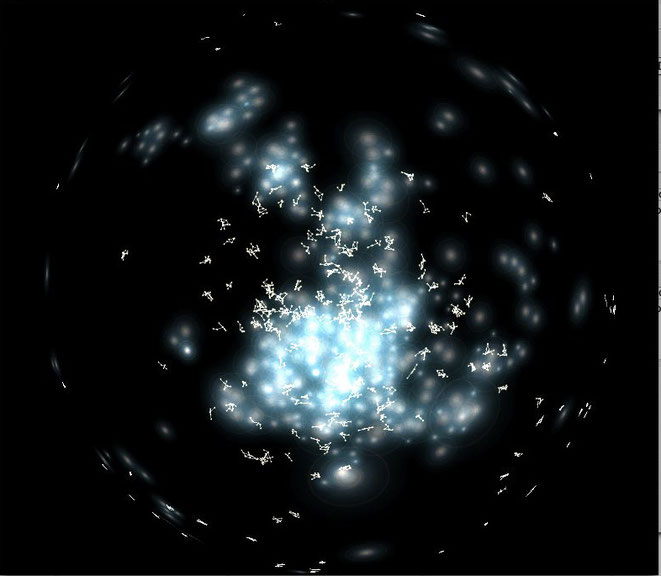

Imagine the night sky as an overarching dome, filled with thousands of shimmering points of light. Each of these bright stars represents the stock of a publicly traded corporation. The intensity of their luminous presence varies in real time according to the frequency of trading. If one star co-varies with others – that is, if a pattern emerges between the rates at which certain stocks are bought and sold – then the flickering points of light draw slowly together, forming unstable constellations.

The illuminated dome is an artwork by Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, entitled »Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium«. It refers both to the financial economy and to ancient astrological techniques for the calculation of human destinies. At first glance it might resemble dozens of other stock-market visualizations, remarkable only for the astrological metaphor. But a further element transforms it into an existential allegory of contemporary social relations.

To create »Black Shoals«, the artists worked with artificial-life researcher Cefn Hoile, who developed computer algorithms for the generation of »creatures« that would feed off nutrient energies released by the traded stocks. On the basis of the programmer\\\'s genetic codes, populations of creatures are born, grow, reproduce and die, developing unique survival strategies that cannot be predicted in advance. Like traders, they form vast alliances or operate warily on their own, display tremendous mobility or remain fixed in one position, focus solely on particular stocks or cast their nets across the entire virtual universe. And like traders, they are affected both by the fluctuations of the market in general and by the strategies of their rivals. A photo documenting the work shows a dense cloud of tiny A-life agents. The caption reads: »These creatures would breed voraciously when they found food, causing huge swarms which would spread across the dome eating everything in their path and eventually dying out when nothing was left to eat. «2

If this allegory of the trader\\\'s condition can be termed »existential« it is not because the creatures are alive in any natural sense, but instead because their artificial world is decisively shaped by a complex flow of data streams whose relations continually border on chaos. But does the allegory apply only to the denizens of the global exchanges? In his General Theory, Keynes famously used the image of »animal spirits« to evoke the affective enthusiasms that motivate market behavior. Drawing on that image, the underground cultural critic Matteo Pasquinelli has compiled an entire bestiary of postmodern parasites whose life-support depends on the surplus values generated by electronic trading.3 He suggests that the form of our cities, the organization of our labor, the content of our entertainment – and, I would add, the rules of our lawbooks and the teleological principles of our arts and sciences – are all dependent on the greed, fear and irrational exuberance that drive the denizens of the electronic markets. They provide the common underpinning for contemporary urban existence. Seen from this perspective, the »stars« of global finance gleam with dangerous passions, and hyper-competition rules our creaturely destinies.

As the economic crisis shows, nothing has more powerful effects at ground level than the shifting map of the financial stars above. The artists put it like this: »Because the stock market has the kind of cybernetic properties of biological systems and other complex phenomena (feedback loops etc.), it can be studied in the same way as biological systems. This tends to give rise to a sense that the market is somehow a »natural« expression of some fundamental forces. One of the lessons we learned in our long journey to understand something about the operations of big finance is that the market is only a natural expression of the particular artificial world model that it embodies – in the same way that the artificial life creatures in Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium are natural expressions of the computer program that they exist in.«

What is the »artificial world model« that contemporary civilization has come to embody under the influence of speculative finance? Will the »creatures« of this peculiar world now have to dramatically change survival strategies, or perhaps even die out and disappear in the wake of the current crisis?

Mirror Maze

Writing in 1986, Susan Strange described the extreme volatility of the financial sphere as »casino capitalism.« While investment bankers made fortunes, risk and instability arose to dominate everyday experience: »The great difference«, Strange writes, »between an ordinary casino which you can go into or stay away from, and the global casino of high finance, is that in the latter we are all involuntarily engaged in the day\\\'s play.«4

The casino opened its doors when the Bretton-Woods fixed exchange-rate scheme was definitively abolished in 1973. The new regime required the hedging of international payments by purchasing a whole range of foreign currencies. The appearance in that year of the first networked currency trading system, the Reuters Monitor, marks the departure point for the ongoing proliferation of financial information networks. What became crucial in the trading pits was the relation of the speculating individual to the ciphers of opportunity flickering on the screen. As Urs Bruegger and Karin Knorr Cetina explain, in an article on »The Global Lifeform of Financial Markets«: »The screen is not simply a »medium« for the transmission of messages and information. It is a building site on which a whole economic and epistemological world is erected. The world-character of this site also comes about through the performative possibilities of the dealing systems implemented on screen.«5

1973 also saw the publication of the Black-Scholes option-pricing formula. Two University of Chicago professors, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes, sought secure foundations for an obscure financial instrument known as a »European call option« – a contract granting the right to buy shares of a stock for a guaranteed price at a future date. Their strategy was to assemble a fictional portfolio of stocks and options, and develop a technique of »dynamic hedging« to continually buy and sell shares, balancing out the fluctuations in price among the separate elements of the portfolio. The price of the option would be equal to the cost of continually hedging against possible changes in the value of the underlying stock. Using equations derived from the physics of Brownian motion, they created a mathematical proof and a theoretically risk-free trading technique that used a carefully weighted constellation of values to distribute randomly occurring fluctuations back into the statistically regular equilibrium of the market as a whole.

The Black-Sholes formula lies at the origins of the »artificial world model« of financial capitalism. Its success touched off a veritable supernova of derivatives trading, reaching a potential or »notional« value of $683.7 trillion in mid-2008.6 But it is also the source of a fundamental disconnect between the informational sky above our heads and the existential ground beneath our feet. On the one hand, the expertise of the »hardest« natural science, physics, provides the bedrock of quantitative certainty. On the other, the »performative possibilities of the dealing systems implemented on the screen« are what actually generates the profits, pumping the animal energy of the trader\\\'s passions into the financial stars above our heads and sparking the positive feedback loops of bubble economics.7 For the cycle of profit-taking and reinvestment to continue indefinitely – that is, for the sky to take on a life of its own – just one further element was needed: systemic corruption that could subvert the checks and balances designed to prevent speculative bubbles. This corruption takes the form of »control fraud«, or the ability of corporate officers to suborn the regulatory instances, both internal and external, that are supposed to keep the system in balance.8 Corruption at the top can transform control functions – accounting firms, ratings agencies, even Greenspan\\\'s Fed itself – into delusional devices for the maintenance of confidence, despite the obvious signs of market failure.

The word »speculation« comes from the Latin verb »specere«, which means to look – in this case, to look into the future. But it is also related to speculum, or mirror. What the world model of financial capitalism does at ground level is to transform select living environments into grotesquely magnified reflections of the primary relation between the grasping trader and the profit-making opportunities flickering on the screen. The gentrification process that reached global scale in the mid-2000s has transformed entire cities into glittering mirrors of the narcissistic desire to gaze into an ever-more opulent future.9 Art, in the instrumentalized form of the »creative industries«, has been an important vector of this total makeover. Take one example of the results: the construction of flashy postmodern casinos in the impoverished core of Detroit, as a predatory regeneration strategy for a ruined city. No longer a production zone, the urban environment has become a stage for an infinite variety of speculative performances. Evoking the supposedly unlimited potential of human capital, these performances seek to justify future investment – in oneself, the land, a product, an algorithm, a business. Yet they take place under highly ambiguous circumstances, where the performer is often a »mark« the target of someone else\\\'s strategy.

The texts by the artists of Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium suggest the existence of self-reinforcing ties, or positive feedback loops, between the A-life creatures and their objects of financial desire. But the programmer, Cefn Hoile, tends to portray his creations as victims of a financial universe beyond their ken: »The creatures’ relationship with their artificial world of stars is a mirror image of our relationship with the financial markets – they strive to survive, competing with each other in a world whose complexity they are too simple to fathom.«10 By accentuating the victim\\\'s role, the allegory largely misses the predatory nature of creaturely existence. For not only do real-life traders prey on each other and on the assets or savings of smaller, more gullible investors, and not only do the banks and the great corporations prey upon each other and on consuming populations. In addition, the entire bestiary of financialized civilization gradually becomes imbued with the relations between hunter and hunted; the relationship that the American sociologist, Thorstein Veblen, first described a century ago in his »Theory of the Leisure Class«.

Today, the passion for the hunt has spread throughout the body politic. It lays the affective basis for what James K. Galbraith calls »the predator state«: a form of governance without any notion of solidarity, which encourages everyone to aspire to the condition of the hunter while at the same time delivering them over to the opposite fate of the prey.11 As Matteo Pasquinelli points out, representations of such base passions are rarely to be found in the idealizing images of contemporary art, which tend either to bow before the overarching logic of code or to exalt the febrile flights of desire. For an image of the predator society I am tempted to look back, not all the way to Veblen\\\'s time, but to the »Magic Mirror Maze« of Orson Welles\\\' film noir classic, »The Lady from Shanghai«, released in 1948 at the very outset of America\\\'s rise to hegemony. The surreal closing scene of the movie offers a prescient glimpse of the distorted realities generated by the spectacular power-brokers of the neoliberal democracies.

The hero of the film is the working-class Irishman Michael O\\\'Hara, played by Welles himself. Following a chance encounter in New York, O\\\'Hara is lured by his own greed and sexual desire into the intrigues of a rich American couple who sail him across the Panama Canal in a private yacht, embroiling him in a complex murder plot that finally leads to the mirror-maze of a San Francisco funhouse. Drugged and disoriented, he witnesses a wild shootout between the rich but impotent trial lawyer, Arthur Bannister, and his exotic wife Elsa, a high-class Caucasian prostitute born in China, played by Welles\\\' estranged wife Rita Hayworth. Faces and bodies multiply in a baroque confrontation of proliferating images, before the first shots ring out. As the mirrors shatter and the labyrinth of reflections falls away in broken shards, the husband and wife finally kill each other, fulfilling what the film portrays as their destiny. The Welles character escapes from the world of distorted spectacle into the open air, wondering how he will forget, how he will live on into the future.

Ask Why

Today it is the mirror-maze of the speculative economy that lies in ruins, and the question is how to forget the impossible desires projected from the financial stars above, how to imagine other destinies. Yet what seems likely, if the current political passivity continues to reign, is that the multitudes of artificial lifeforms that flourished briefly in the glass-house environments of the financial capitals will now just fade away like the swarms of lesser creatures in Black Shoals, leaving the major predators with their weapons intact, still firing at each other. The danger is that the present crisis will be resolved by those at the top of the social hierarchy, who are now attempting to reboot the speculative economy. In that case, the profound reshaping of social institutions required to end the crisis will be decided exclusively by them. If we want to make an egalitarian change in our world model, it is urgent to understand what happens in the boom-bust cycles – before they are used against us once again.

»Ask why« was the slogan of the former energy-trading corporation Enron, whose opaque financial strategies, illegal business maneuvers and extensive support in Washington made it an exemplar of control fraud at the turn of the millennium. An advertisement aired just before bankruptcy in 2001 shows three businessmen with seeing-eye dogs and the heads of mice, wearing dark glasses and tapping the ground with white canes. The off-screen voice explains: »Enron Online [...] is creating an open, transparent marketplace that replaces the dark, blind system that existed.«12 The slogan is a classic symptom of the speculative economy: an injunction to know that reverses into its opposite. »Why ask?« is the real message. At stake here is the function of the veil, which turns sophisticated knowledge, indeed visibility itself, into a weirdly transparent cloak of secrecy and denial. Visible blindness is the underlying formula of financial governance.

A similar blindness dominated the epoch of industrial production. Marx described the commodity as that product of human labor whose exchange value, seemingly animated with a life of its own, acts to render invisible the social relations that produced it. Derivatives, however, have nothing to do with production as such; instead they are conceived to manage the environmental risks that weigh on the future of speculative activity. In this sense they are meta-commodities that govern the unfolding of the contemporary economic model. Their fascinating appearance acts to conceal the private deliberations that effectively shape the environment in which any productive or consumptive activity can take place.13

The lifeform of the financial markets is now animated by these meta-commodities, which lend the new cityscapes their dazzling character. But what the pulsating lights of the central business districts hide is the privatization of the social state – indeed, the privatization of government. Gentrification is the fetishism of severed democratic relations. Yet the collapse of this economy can also have its payoffs. Consider the way that Enron\\\'s manipulation of energy markets led first to rolling blackouts in California, then to the recall of the Democratic governor Gray Davis and the election of Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has used the credit crisis as an historic chance to destroy public services.14 In the name of future prosperity for the middle-class citizens of California, the »Governator« is terminating public funding for the socialized university system that allowed so many Californians to achieve middle-class status. What European activists call »precarity« – that is, a condition of generalized uncertainty regarding education, employment, housing, health care, retirement and other life chances – now appears as a destiny, rising up against horizons blocked by the advancing threat of climate change. The supernova has finally imploded, leaving black holes in the future.

As the sociologist Daniel Bell wrote in 1973, »the »design« of a post-industrial society is a »game between persons« in which an »intellectual technology«, based on information, rises alongside of machine technology.«15 Can we finally ask why the citizens of the world\\\'s democracies accept the playing of such strange games between people, where they are alternately the hunter and the hunted? In the great hall of Chicago\\\'s Merc or in the proliferating electronic spaces of the GLOBEX network, derivatives traders hold up a distorting but oddly faithful mirror to the wider worlds of so-called »digital labor.«

At the outset of this decade, in a text entitled »The Flexible Personality«, I identified a widespread desire among the new knowledge workers to mix their labor with their leisure in an enticing or even eroticized atmosphere of free play.16 A hilarious image from the »Yes Men«, showing a corporate executive in a skintight »Management Leisure Suit« with an electronically networked »Employee Visualization Appendage« rising like a golden phallus from his hips, served to make the point. The kind of »play-labor« celebrated by the pundits of Web 2.0 may have had transgressive connotations in the 1960s, but today it is only a grotesque parody of Huizinga\\\'s »homo ludens«, and a woeful caricature of the sublimated sexuality that Marcuse envisioned in his revolutionary book, »Eros and Civilization«. What has disappeared from the networked cultures of casino capitalism is the willingness to engage in political conflict – even while the civilizational forces of Thanatos, or unbridled aggression, bear down on the biosphere. Now it is those aggressive drives that must be sublimated and channeled into a necessary struggle. Rather than draping aesthetic and epistemological veils over blatant expropriation, shouldn\\\'t artists and knowledge workers seek political confrontations with those who set the rules of the game?

The struggles against privatization that began unfolding in September 2009 within the University of California system (and therefore at the heart of what autonomous Marxist theorists long ago identified as »cognitive capitalism«17) have finally opened up a significant grassroots challenge to the logic of the predator state and the financial world model that it incarnates. The California outbreaks were preceded by major student movements in France, Italy and Croatia, and followed about a month later by parallel events in Austria – only the latest in a worldwide wave of cycle of protests refusing the instrumentalization of higher education. These struggles are important, because the university has become the crucial laboratory of neoliberal management and financial engineering, in addition to its traditional role as R&D center for the industrial war machine.18 Only far-reaching changes in the ways that knowledge is elaborated and made productive can reorient our complex societies away from the suicidal pathway of climate chaos and generalized warfare, steering them instead toward a sustainable and survivable future.

Addressing himself to European artistic vanguards steeped in the heritage of Italian Autonomia, Matteo Pasquinelli calls for »the sabotage of creative value« and »the explosion of the social relations enclosed in the modern commodity.«19 In the university, that would mean trashing the concept of individual market freedom and prying open the meta-relations of governance that are concealed in abstruse mathematical formulas. Such an explosion has become urgent. We need a different world model, which cannot be abstracted from price information analyzed by computers. But it will take more than critical insights to gain anything concrete. Beneath the curve of the night sky there awaits, not only occupations of public buildings and demonstrations on the streets, but also an existential struggle for the quality of our dreams. Critical intelligence and the radical imagination will have to merge with the animal spirits of political conflict, to chart new paths through the fateful spaces where symbolic constellations are etched on living skins.

This text was slightly shortened by the author for the German translation.

1 Cf. Amy Terpstra, Amy Rynell, & Andrew Roberts, »2009 report on Chicago region poverty« (Chicago: Heartland Alliance Mid-America Institute on Poverty, 2009), available at http://www.heartlandalliance.org/research.

2 This and the following quote can be found in the extensive documentation at http://blackshoals.net.

3 Matteo Pasquinelli, Animal Spirits: A Bestiary of the Commons (Amsterdam/Rotterdam: Institute of Networked Cultures/NAi publishers, 2008), ch. 1.

4 Susan Strange, Casino Capitalism (Manchester University Press, 1997/1st ed. 1986).

5 Karin Knorr Cetina and Urs Bruegger, »Inhabiting Technology: The Global Lifeform of Financial Markets«, in »Current Sociology 50« (2002).

6 http://www.bis.org/publ/otc_hy0905.pdf

7 For an introduction to positive-feedback theories of the economy, see Melinda Cooper, »Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era« (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), ch. 1.

8 William K. Black, »The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry« (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005).

9 See my article »Megagentrification«, http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2008/12/06/megagentrification.

10 Cefn Hoile, »Black Shoals : Evolving Organisms in a World of Financial Data«, available at the author\\\'s website: http://cefn.com/cefn/?BlackShoalsPaper.

11 James K. Galbraith, »The Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the Free Market and Why Liberals Should Too«, 2nd ed. (New York: Free Press, 2009).

12 The ad is archived at www.rtmark.com/enron.

13 For a parallel treatment of the metacommodity, see Brian Holmes and Claire Pentecost, »The Politics of Perception: Art and the World Economy«, in »What Keeps Mankind Alive? The Texts«, catalogue of the 11th Istanbul Biennial (Sept. 12-Nov. 8, 2009), pp. 344-55; available online at http://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/09/26/the-politics-of-perception.

14 See the documentary on Enron by Alex Gibney, »The Smartest Guys in the Room« (2005), where the anatomy of control fraud is retraced from the sinews to the bone.

15 Daniel Bell, The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting (New York: Basic Books, 1999/1st ed. 1973), p. 116.

16 Brian Holmes, »The Flexible Personality: For a New Cultural Critique« in »Hieroglyphs of the Future« (Zagreb: WHW, 2002), online at http://eipcp.net/transversal/1106/holmes/en.

17 Antonella Corsani et al., »Vers un capitalisme cognitive« (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001). For an introduction in English, see Carlo Vercellone, »From Formal Subsumption to General Intellect: Elements for a Marxist Reading of the Thesis of Cognitive Capitalism«, in Historical Materialism 15 (2007) 13–36 (available at http://www.generation-online.org/c/fc_rent5.pdf). References to the Italian literature can be found in »Animal Spirits«, op. cit.

18 See Brian Holmes, »Disconnecting the Dots of the Research Triangle: Corporatization, Flexibilization and Militarization in the Creative Industries«, in »Escape the Overcode«, op. cit.

19 »Animal Spirits«, op. cit., p. 49; also see my contribution to a debate with Pasquinelli on the My-ci mailing list on Dec. 18, 2008, at http://idash.org/pipermail/my-ci/2008-December/000554.html.