Issue 2/2010 - Intermedia 2.0

Friedrich Kiesler’s Work in Theatre

The Inception of an Interdisciplinary Universe

When Friedrich Kiesler began his work as a theatre designer in 1923, he immediately began pushing the boundaries of the profession. He brought broad creative potential to the field: he was a theatre artist but also an architect and architectural theorist, as well as a designer whose projects were mostly of a visionary nature and were therefore often misunderstood and rejected. He set new standards in exhibition design, which he understood as stage design. In the middle of his life, he postulated a theory of design that he named »Correalism,« in which his personal views on life, art, and the natural sciences converged. Towards the end of his life, he practiced painting and sculpture as well. Kiesler was able to integrate and interconnect all these different areas. He was driven throughout his artistic life by two or three key ideas that were manifested in every one of his works. Even the most minor design events, such as the display window he designed for the New York luxury department store Saks Fifth Avenue in 1929, are based on one universal concept. Kiesler expressed his views in an essay that contains refreshing reflections on American consumerism. Through his display window designs he hoped, so he writes, to subliminally impart the principles of modern art and aesthetics to the consumer masses sauntering past.1

The Incorporation of Technological Apparatus into the Aesthetic Sphere

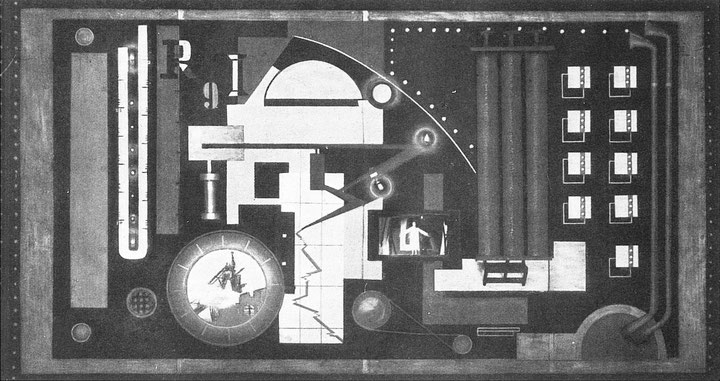

In his earliest works, two stage designs in Berlin in 1923 and 1924, his method was already becoming evident. In 1923, he designed a congenial backdrop for Karel Čapek’s robot drama »R.U.R.«, and one year later, in 1924, the stage set for »Kaiser Jones« by Eugene O’Neill. Both of these early stage designs were based on a universal idea for which Kiesler was burning with enthusiasm at the time. He marveled at the many technological advances of his time and felt compelled to include these in his stage scenery. The science fiction story by the Czech author Čapek, who liked to set his pieces in the future, was practically tailor-made to suit Kiesler’s fascination with technology. He distilled the piece’s essence and found a convincing visual form in which to express it. In a single backdrop that covered the entire rear wall of a small boulevard stage on Kurfürstendamm in Berlin, the optokinetic as well as acoustic inventions of the time were embedded into painted and real machine components and combined to form a relief-like overall image. In this way, he created the perfect setting for a splendid apotheosis of technology. Certain parts of the stage set had actual working parts and possessed a function within the play, which was an entirely new approach in theatre. In a text that was published in 1924, Kiesler described the parts’ functioning as follows: »To the left, a large iris diaphragm with a diameter of 1.10m. The diaphragm slowly opens: the projector rattles as a film begins to play on the circular area. The diaphragm closes. To the right, built into the backdrop, a tanagra device opens and closes. The seismograph in the middle jolts forward in a jerking motion. The turbine control rotates incessantly. Work sirens give signals. Megaphones communicate orders and give answers.«2 There are only a few remaining photos documenting Kiesler’s stage design for »R.U.R.« These, however, circulated in all the avant-garde journals of the day. Soon they reached iconic status and became representative of the renewal of art through the incorporation of technological apparatus into the aesthetic sphere.

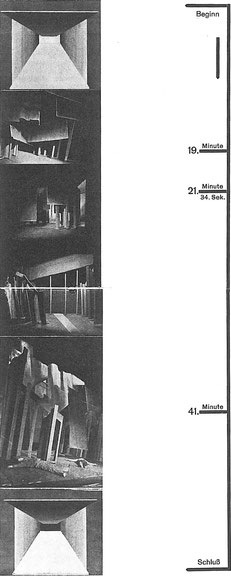

On January 8, 1924, »Kaiser Jones,« the American playwright Eugene O’Neill’s new piece, debuted in Berlin, directed by Berthold Viertel and with stage design by Kiesler. This time, the scenario at hand was not very conducive to Kiesler’s hypertrophic technological visions. He therefore found himself having to retrospectively come up with a reason behind the stage design he created. Having only four photos at hand, which showed the abstract, slightly arbitrary-seeming stage scenery, Kiesler decided to edit this photographic material and simply rename everything. He combined the four photos into a film frame and flanked them with two funnel-shaped spaces, so-called »funnel stages,« which he set at either end of the film frame. These funnel stages were simply sketched in and did not reflect the actual performance. Next to the frame, he attached a timeline that displayed to the second when the backdrop was to change. He accurately and provocatively named the frame: »Sequence of Mechanical Scenery.« He had thus completely detached his concept from the original subject, a theatre piece named »Kaiser Jones.« In the actual performance, there was no abstract play of forms; to the contrary, Kiesler used slats hanging at random throughout the stage area to simulate an African jungle. Kaiser Jones, O’Neill’s tragic villain, was to be harried and hunted through this eerie thicket. In the film frame, the use of photo-montage made it possible to abstract the original subject and demonstrate the bold idea of a mechanized play sequence. Kiesler, a utopian and visionary, would continue to deliberately transcend the bothersome restraints of reality time and time again, in order to realize his visions on his own terms. With these two stage settings, which he later cited often in his writings, describing them as »electromechanical backdrops,« Kiesler pioneered an innovative new approach to stage design in the 1920s. He also demonstrated a masterful command of the art of naming his creations. Finding the right catchphrase, or even better: the right battle cry, was extremely important in order to prevail in the competition of ideas—which at the time were abundant. His gift for innovation was immediately recognized by his contemporaries, and this success gave Kiesler the strength to achieve further feats, first by launching a massive attack on European theatre and its traditions, and second by rebuilding it from the ground up.

A Change in Scale and Function: From Space Stage to Space City

In 1924, Kiesler was called to Vienna for a special commission. The organizers of Vienna’s Music and Theatre Festival found that two sensational stage designs and three theatre manifestos published in Berlin newspapers—pieces that packed explosive power—formed exactly the right mixture of practice and theory to distinguish Kiesler and qualify him to create an exhibition on European avant-garde theatre. This turned into the legendary »International Exhibition of New Theatre Techniques,«3 which took place in the autumn of 1924 in the rooms of the Vienna Konzerthaus. In this design task, Kiesler for the first time pulled out all the stops, showcasing his stupendous creative versatility. He was not interested in specializing in and increasingly perfecting just one area of design. Instead, he recognized his era’s need for a new, universal language of design. It was up to a universalist such as himself to apply one workable idea to all conceivable design fields. In Vienna, he developed his entire concept out of the spirit of Constructivism: the typography used for the poster and catalogue, the system of beams and girders employed in the exhibition’s design, and especially his »Raumbühne,« or »Space Stage.«

It was downright shocking to everyone involved, supporters as well as opponents, to see the Space Stage standing in the middle of the Konzerthaus in its full—and fully playable—size. The Space Stage extended from the orchestra up to the balcony, where the audience was grouped into a U-shape around the towering stage. Kiesler’s Space Stage effectively encapsulated the avant-garde reforms to stage design in his day while putting them to the test. This sort of real-time experimentation was extremely unusual in a period where theatrical utopias were rarely realized. People had almost become accustomed to dreaming of projects that could never be brought to life. It is for this reason that Kiesler’s Space Stage made such a splash. Kiesler had galvanized these tentative attitudes by proving that the realization of a new type of stage was possible after all. The Space Stage was a high stage-tower designed as an exposed, extremely dynamic-looking wooden structure. An elevator within the tower’s shaft transported the actors to the central ring of the stage. The uppermost, round platform could be accessed from the central ring via two steep iron ladders or from below via a wide stairway. A spiral ramp led from the orchestra to the central ring. Only a single production was staged on the Space Stage: »Im Dunkel« (In the Dark), a three-person play by Paul Frischauer. Composed in Late Expressionist style, it was a further addition to the countless embezzlement dramas in the style of Georg Kaiser. A second production, of the Dadaist grotesque piece «Methusalem« by Ivan Goll, failed shortly before its premiere due to copyright problems. During the three weeks that the Space Stage stood in the Konzerthaus, it was often used for dance performances, and perhaps it was truly meant to be the perfectly congenial stage setting for modern, gymnastics-focused dance.

Most theatre critics at the time vehemently criticized the Space Stage. One of them was Karl Kraus: »So you think, Herr Kiesler, that Gretchen should race up to the platform on a motorcycle, then sing her song at the spinning wheel up there before zooming downstairs in the elevator, while in the meantime Faust and Mephisto roll up the serpentine ramp in a little car? Herr Kiesler calmly answers: ›I do not think we will be playing Faust.‹«4

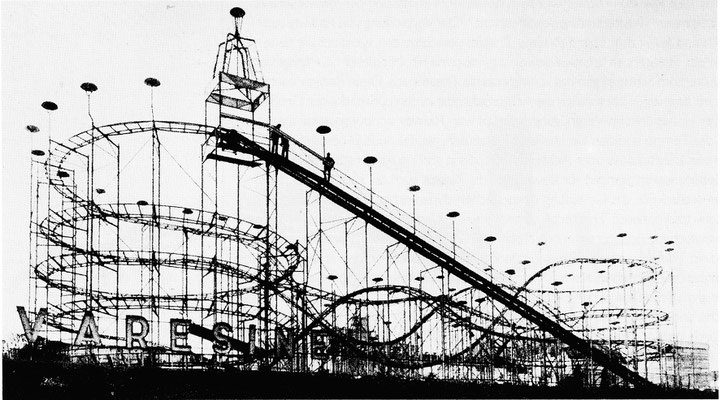

Manifesto literature, a crucial supplement to a full understanding of avant-garde art, peaked in popularity in the 1920s. Kiesler was a master of this medium. Nobody was as adept as he at attacking traditional theatre. In his manifestos he took an even more radical approach to theatre reform than he had already succeeded in realizing through his Space Stage. In a 1924 text, he called for a »Railway Theatre.« The Space Stage was also to be a part of this complex theatre structure. »The Space Stage of the Railway Theatre, the theatre of time, floats in the space [...] The auditorium loops around the spherical stage core in electromotor locomotion [...] the area of movement becomes poly-dimensional, that is, spherical [...]«5 The kinetic energies deployed in Kiesler’s theatrical concept mimicked those of the imposing steel roller-coasters that were the sensation of every fairground at the time. Since these technologically advanced pieces of leisure architecture came from America, in Europe they were commonly called »Railways.«

In 1925, Kiesler was invited to design a presentation on contemporary Austrian theatre at the grand exhibition »Exposition Internationals des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes« in Paris. Not one of his works as a theatre artist was on display there. What he created in Paris was a refined and optimized version of the exhibition design he had employed in Vienna. He designed an almost floating scaffold construction that was originally intended to serve the purpose of presenting stage models and designs by Austrian theatre artists. However, its initial function was to be joined by a further, entirely new one. In order to achieve this, Kiesler, like a magician, set in motion a mechanism that transformed his creation into something completely different. To him, his construction exemplified a much broader idea—a model of a future city, which he evocatively named »Space City.« The public announcement of »Space City« followed immediately after this »flash of genius,« on a flyer written in collaboration with Maurice Raynal, which was handed to the exhibition’s visitors. In the same year, 1925, Kiesler’s manifesto »Vitalbau – Raumstadt – Funktionelle Architektur« appeared in the Dutch art journal »De Stijl.«6

The importance of this idea of space to Kiesler was later illustrated by his attempts at transferring the concept to a family home. In 1933, he developed the »Space House,« a prototype of which was built and displayed in a well-known New York furniture store. We may well wonder whether the term »Space House« is an unnecessary pleonasm. Alfred Kerr, a prominent Berlin theatre critic, had already taken issue with Kiesler’s term »Space Stage.« He found it hard to imagine a »no-space stage,« he wrote in a 1924 review.7 However, one could argue that the term »Space Stage« with its downright ingenious doubling of meaning was exactly what Kiesler needed to make clear that this was a completely novel type of stage. It was intended to be a stage that made »space« come alive—in contrast to the traditional picture stage, which already dismissed space in terms of its terminology.

Transferring the Stage to the Department Store

When Kiesler announced his ideas for a »Space City« in Paris in 1925, he was discovered by Jane Haep, who was in Paris at the time, allowing him to gain access to the American scene. She was the editor of the avant-garde literary journal »The Little Review« and managed a gallery in New York. She invited Kiesler in 1926 to co-design a third version of his theatre exhibition with her in New York. Meeting her proved momentous, for Kiesler and his wife, Stefi, resided in New York from that point onwards. Having arrived in New York in the spring of 1926, Kiesler designed the »International Theatre Exhibition« in his usual manner, in an extremely short amount of time, and perhaps with a slightly reduced budget. The exhibition showcased the foremost European theatre designers, as well as modern American theatre art and its own heroes, such as Norman Bel-Geddes and Edmond Jones. Of his own work, Kiesler presented not only his tried and tested theatrical inventions, such as the »electromechanical set« and the »Space Stage,« illustrated only in the form of images. He also confronted the New York audience with a completely new, powerfully visionary and utopian type of theatre. Specifically for New York, he created »Universal the Endless Theatre without Stage.« This egg-shaped theatre, which he exhibited as a plaster model complemented by several large-format floor plans and elevations, gave the impression that it could possibly be built in the near future. The concept »endless« was to become a central idea in Kiesler’s architectural as well as his theoretical and creative work. He explored the notion of endlessness most plainly in his architectural fantasies. The group of works that we so admire nowadays, Kiesler’s cavernous, organically sprawling houses, also grew and evolved from the spark of theatrical ideas. He envisioned his first »Endless Theatre« in 1926, as a flawless egg shape that ideally represented the infinite, a flowing construction without a beginning or an end. For the exhibition, Kiesler paired this new theatre design with another, second theatre project that he named: »Railway Stage for Department Store (The endless stage).« This second project was created through an incredibly provocative act: in a fury of destruction, he removed the stage from his »Endless Theatre without Stage,« the egg-shaped theatre, in order to replace it with a profane department store. Upon coming to America, Kiesler had soon become aware of the theatrical potential that lay fallow in the splendidly arranged department store product displays. On the spiraling ramps that twist around his department store’s central axis, the shoppers stepped onto the theatre stage while the goods provided a decorative backdrop and the act of buying became the dramatic plot. Reality had caught up with this theatre and rendered it obsolete. Kiesler emphasized this radical approach in a manifesto with the telling title »The Theatre Is Dead.«8 In the 1926 exhibition catalogue, this text became the central theme prefacing the entire content.

It was not long before the dire financial situation put an end to Kiesler’s visionary flights of fancy. He became more pragmatic. In 1928, he built a movie theatre based on the ideal conditions for film viewing, and between 1929 and 1931 he designed two functionalist theatre buildings, so-called double theatres, one for Brooklyn, the other for Woodstock. In both cases, the buildings were never realized.

Surreal and Galactic Worlds

After 1933, Kiesler’s design principles underwent a spectacular transformation. He abandoned Constructivism-influenced design and absorbed the ideas of Surrealism, which was winning ground in New York at the time due to the onset of a wave of immigration of Surrealist artists from Europe. In his new job as director of scenery for the operas put on by the students of the prestigious Juilliard School for Music, he opened the gates to allow the boisterous power of Surrealist imagination to pour into the still highly conservative world of opera. He freed the scenic space in which the opera took place from servitude to banal, decorative realism.

The 1934 production of »Helen Retires,« by the American composer Georges Antheil, as well as »The Poor Sailor« by Darius Milhaud in 1948, are both successful examples of his Surrealism-inspired stage scenery. For the ancient Greek setting in »Helen Retires,« for which John Erskine wrote the libretto, Kiesler created abstract masks that obscured the singers’ faces, as well as soft, organic, almost Arpian shapes that were intended to symbolize the interplay between the world and underworld as a dreamlike spectacle. For the opera »The Poor Sailor,« he used maritime flotsam and jetsam such as seashells, fish bones, roots, and driftwood to create a surreal world of forms reminiscent of Surrealist paintings. One of the opera’s central settings was the sailor’s hut. Kiesler constructed it from an extremely permeable frame consisting of odd bone-shaped, branch-like parts. Once the performance series was over, Kiesler extrapolated this hut from its stage context and declared it to be an autonomous installation. He named his series of large room-filling sculptures »Galaxies.« And yet, although the idea behind this series originated in theatre design, Kiesler developed and transformed it in such a way that its connection to theatre was eliminated entirely.

The »Universal« or »Endless Theatre,« which Kiesler worked on from 1959 to 1961, was his final work in theatre. In 1959, Kiesler, along with seven other artists, was asked by the Theatre Guild in New York to design an ideal theatre. This request evolved into a major theatre project that Kiesler laconically named »The Universal.« Numerous designs and plans for his project, as well as a large aluminum model, are currently on display at Harvard University’s Theatre Museum. In this theatre project, Kiesler was able to master the difficult balancing act between vision and pragmatism. He placed a ten-story skyscraper atop the freestanding theatre building’s sprawling round, biomorphic back. Kiesler the utopian explained in the text accompanying the project that it is not economical to plan a theatre as a single, freestanding building, as had been customary thus far.9 The air space just above was too expensive and precious to ignore. His theatre took on an unusual form: a cavern, a uterus shape. Its content however—it was a multifunctional theatre with a flexible stage—was functional and very practically thought-through.

Translated by Jennifer Taylor

1 Frederick Kiesler, “America adopts and adapts the new art in industry,” in: Siegfried Gohr, Gunda Luyken (eds.), Frederick J. Kiesler – Selected Writings. Ostfildern near Stuttgart 1996, pp. 10–14.

2 Friedrich Kiesler, “De la Nature morte vivante,” in: F. Kiesler (ed.), Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatretechnik, exh. cat. Vienna 1924, p. 21.

3 A comprehensive discussion of the »International Exhibition of New Theatre Techniques« as well as an analysis of the »spatial stage« can be found in: Barbara Lesák, Die Kulisse explodiert. Friedrich Kieslers Theatreexperimente und Architekturprojekte 1923 – 1925. Vienna 1988.

4 Karl Kraus, “Serpentinengedankengänge,” in: Die Fackel, nos. 668–675 (December 1924), p. 39.

5 Friedrich Kiesler, “Das Railway-Theatre,” in: F. Kiesler (ed.), Internationale Ausstellung neuer Theatretechnik, exh. cat. Vienna 1924, p. II.

6 Friedrich Kiesler, “Manifest: Vitalbau – Raumstadt – Funktionelle Architektur,” in: De Stijl, issue 10/11, 1925 (reprint Amsterdam/Den Haag 1968), pp. 435–437.

7 Alfred Kerr, “Eugene O’Neill: Kaiser Jones,” in: Berliner Tageblatt, January 9, 1924.

8 Friedrich Kiesler, “The Theatre Is Dead,” in: The Little Review, special theatre issue, New York, Winter 1926, p. 1.

9 Frederick J. Kiesler, “The Universal,” in: The American Federation of Arts (ed.), The Ideal Theatre: Eight Concepts. New York 1962, pp. 93–94.