The artist Markus Schinwald has for quite some time now been working with different media and in different genres, such as clothing, installation, drama, dance and film. His latest exhibition, »Vanishing Lessons« (2009) at Kunsthaus Bregenz, brought all of these groups together in a major installation. In an in interview with Georg Schöllhammer, he explains why art doesn’t have to present itself as conciliatory at all costs when closely addressing neighboring domains.

[b]Georg Schöllhammer:[/b] The first thing that comes to mind is a quote of yours about working outside of one’s accustomed field. When Jens Hoffmann launched a survey in connection with the most recent documenta, asking whether an artist should curate that large-scale exhibition, you answered that you were already very busy as an artist: »I’m afraid I have to decline. As an artist, I must admit that I hesitate to begin another career.« You always approach your work in an inter-creative manner, which is exactly what continues to be treated as a problem.

[b]Markus Schinwald:[/b] I must admit that I believe the term »creativity« is relatively useless in art. It is too likely to be misunderstood and it doesn’t hit the mark of what I believe art is all about. When speaking about the creativity of designers and architects etc., it is easy to forget that pop singers, physicists and managers have to be creative, too. The term is so fuzzy that it slips right by art. Art is not about good ideas, although they can’t hurt; rather, it is about a certain attitude – a manager, for instance, who also has to be creative, might face completely different problems, and here the question of attitude is totally different, too.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] The concept of intercreativity, I would assume, does not preclude the fact that physicists, teachers or priests also have to be creative. But what needs to be discussed first and foremost at this point is the potential among the individual genres. Your answer, and that is also noticeable in the humanities, goes in the direction of having to defend a discipline. There is a disciplinarity, not just an interdisciplinarity. If intercreativity exists, then only because I am interested in integrating it into my own discipline. Do I understand you correctly in this regard?

[b]Schinwald:[/b] I see very pragmatic problems. I have worked on occasion with theatre people, mostly with dancers, and I tried to get the disciplines to overlap somewhat. Unfortunately, at least one area was always curtailed. The individual disciplines’ conventions already present an obstacle. A few years ago, Tanzquartier Wien invited me to participate in a project, but I’m afraid the result was interesting mostly from an artistic point of view, not as much from the perspective of dance. Art’s historic development just did not proceed in parallel to the history of other disciplines.

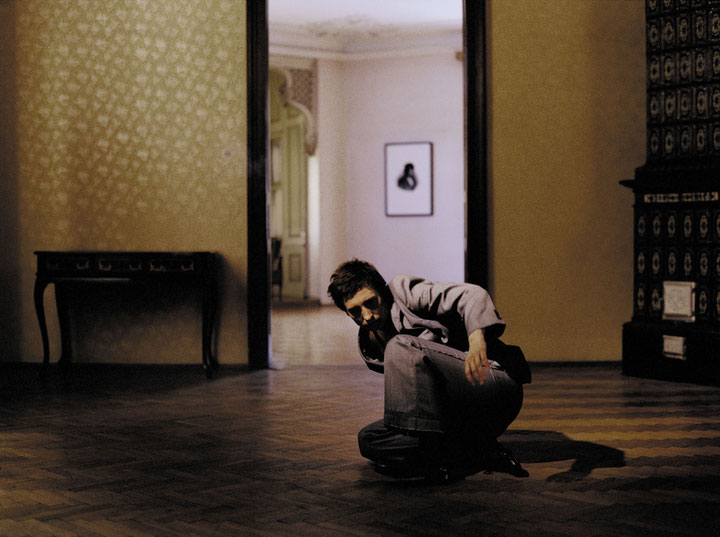

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] Your work has developed: you’ve gone from grappling with what happens between fashion, sculpture and the body when cinematic motifs or scenic portrayals are added, to dealing with figures of movement in art, sculpture and dance. Recently, you had a presentation at Kunsthaus Bregenz where you turned back this development in an almost exemplary fashion. You had actors, dancers – basically people who move in different ways – perform the scope of possibilities within a certain setting.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] A word about how my work developed: I started with clothing in the mid-late 1990s when that was fairly en vogue. With a bit of luck, I was included in several exhibitions, but I never really felt comfortable in that context. For me, it was never about fashion, but about what clothing does with/to the body. So I expanded my radius a bit, added dance and film and then, somehow, everything merged seamlessly. I realized that some fields cover certain aspects better than others. Photos do not have sound, but all the same, film doesn’t necessarily triumph.

Regarding the Bregenz exhibition, it was actually based on the project I mentioned at Tanzquartier Wien. TQW director Sigrid Gareis gave me carte blanche, so I was basically able to do whatever I wanted. The Tanzquartier’s program is beholden to a kind of avant-garde tradition: in a cultural hierarchy, it would rank at the top of the list. That was something I wanted to fracture a bit, so I looked at what was at the other end of the spectrum of this hierarchy, where I found the sitcom. In Los Angeles, I researched how sitcoms are made and then applied that structure one-to-one. The idea was to let the story begin in Vienna and then have it travel – I had loose partnerships in Belgium, the USA and in Graz. In Brussels, we were going to find five doubles for the Viennese actors and actresses; in New York, we’d find doubles for the Belgian actors and actresses and so on, like the game Chinese Whispers, where you end up with something totally different from what you started out with. The directors and curators of the respective partner institutions were present for opening night and they thought it was awful – awful enough to disinvite me.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] What was their criticism? Regarding intercreativity, how close disciplines appear to be to each other but how far apart they really are is by no means insignificant.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] They are very far apart from one another, I’m afraid to say. One of the main critical points was that the play was too boring. If you’ve studied the history of performance at all, this criticism sounds odd – there are performances where a naked man scratches his ear for an hour and no one thinks it’s boring. My performance lasted for an hour and a half and had what it takes not to be boring. A lot happened: there were cameramen, actors, production assistants, costume designers and so on, and they were all busy on stage. But it was out of the ordinary. We wanted to film 15 minutes of material every day, and from experience I can say that it takes about an hour and a half to get enough worthwhile footage – if a cameraman takes a bad pan shot, an actor sneezes etc., you have to start all over again. Finally, it’s these mistakes that make the evening. One of the arguments was that the dramaturgy was bad. I felt that was a misunderstanding, as it wasn’t about the hour and a half, but about how such a work is constructed and what is staged and what isn’t. Before my mind’s eye, I saw readymades, which have not been an issue in art for a long time. In art, we’ve seen it all, but on the stage, the concept has not really arrived yet. I transferred the structure of a sitcom one-to-one and didn’t try too hard to make the performance and the dialogues more sophisticated than a sitcom does.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] A second genre that you employ to a large extent is the intersection between cinema and television. Your video works tend strongly toward cinema, while the installations are more along the lines of television as a possible foil against which sculptures are erected. In the end, however, it’s always about the relation between bodies, sculptural relations, a conventional staying-within-the-discipline in order to confirm the discipline along its borders. Freud’s model of the uncanny as a possible form of the other can be applied to your cinematic works, which people like to compare to David Cronenberg or David Lynch. You once said about these works that to you, they were like bits taken from the edges of a film, bits without a core, without an end – garbage that is mirrored in itself. Often the actors come from a different genre, for example from dance.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] In this case, I would describe my cooperation as being more like a kind of complicity where you also work with the idiosyncrasies of the individual partners. You don’t meet at the same level; rather, if you like, at a slanted, or even better, a seesawing level where you take turns being up. Once I had to give the cameraman a false briefing in order to get the right result. At the same level, his knowledge of making films would have been vastly superior to mine and I would never have gotten what I wanted. I believe that a quintessential difference between certain creative fields and art is that art isn’t a forgiving medium in itself. Theatre is forgiving, and film is actually a reconciliation with the world, and design of course as well.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] It’s also a reconciliation with a world that began in the 19th century – bourgeois culture, or rather the culture of capitalism. It is quite noticeable that the early or mid-19th century is an important point of reference in many of your works. Your portraits often hint at Biedermeier engravings; in addition, there’s a fascination with corsages and corsets, or with apparatuses that expand the body. You often furnish your films with 19th-century late bourgeois interiors. Where does this interest come from?

[b]Schinwald:[/b] Probably from the idea of the fetish, or the prosthesis. I always envied the fetishist his imagination – that someone uses an object to find the key to another world. And an artificial limb corrects a kind of deficit. But of course, that doesn’t stop with the 19th century; high heels are also a kind of prosthesis.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] That almost automatically leads to a remark Freud makes in his »Civilization and its Discontents«: »Man has, as it were, become a kind of prosthetic God. When he puts on all his auxiliary organs he is truly magnificent, but those organs have not grown on to him and they still give him much trouble at times.« Fantasies of dissolving the body accompany the arts in the second half of the 20th century, reaching all the way to cyberspace. Couldn’t what is prosthetic about a technical or sculptural construction serve as a link between the world of objects, the objects of the deceased and the Other?

[b]Schinwald:[/b] References to Freud, and that includes his definition of the uncanny, have often been applied to my work; that is nearly unavoidable when working with the body and the difficulties a body makes, but at some point, it becomes too much. I have tried to correct that or at least challenge it by introducing other focal points. I’m not interested in creating a chamber of horrors or a haunted house.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] In the Bregenz exhibition, you tried to correct it by using »practical jokes« abundant in sitcoms.

Schinwald: Yes and no. I turned the exhibition’s three floors into a television studio. The first floor was very much in line with a traditional sitcom, with the requisite classic jokes. On the second floor, there were several pairs of dancing twins, and on the third, elegant gymnasts. What was hardest was working with the actors. As far as I am concerned, they are too good at what they do. In Austria, most of them come from a theatre tradition and when they act out being angry, they are especially good. But being good at being angry doesn’t always look good on film.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] That means you and the actors fought during rehearsals?

[b]Schinwald:[/b] We already fought beforehand. But sometimes, you just don’t get along well with a certain actor or actress. In one of my productions, there was this one actor who blocked me wherever he could. An hour before the premiere, I bought the tightest, most uncomfortable turtleneck sweater I could find to enhance his disagreeable traits, and then suddenly, it worked. So being mean can also be a productive method.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] That reminds me of a short scene from a documentary film where Jean Renoir is holding a casting for one of his great films, and the actors, all of them from the theatre, interpret every text. Finally, he lets them read the phone book out loud, arguing that in film, you can’t interpret. That’s a wonderful example for the interdisciplinarity between different genres: you have to completely empty one genre before you can fill it with the disciplinarity of the other. If I think about your »1st Part Conditional,« it is a rhythmical movement born from the tradition of avant-garde dance that is immediately reminiscent of something akin to psychic otherness, St. Vitus’s dance etc., which provokes the more narrative readings from cinema and none at all from dance.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] I must admit that I was not terribly interested in dance. In the late 1990s, the Russian-Viennese dance group Lux Flux & Saira Blanche Theatre invited me to work with them. Enthusiastically I accepted, watched the first rehearsal, and was rather shocked. It was a form of free dance I can’t relate to at all. I then designed a costume for each dancer that expressly prevented them from dancing like that. One of them, for instance, wore a shirt, the Jubilation Shirt, in which you could do nothing but rejoice. He was onstage for half an hour, rejoicing. And that is how things continued, somehow. At the beginning, I had separated the history of costumes into two parts. One is the garment, the other is the framework. The garment is what wraps the body, the framework is everything else; it is clothing with an architectural function. Later, I worked with architectural objects that were the exact opposite, that had nothing tectonic about them, for instance curtains. These days, when I work with exhibition installations, they are almost always prostheses for the space.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] In an interview, you once said that you are interested in how a space makes observers decipherable by way of their bodies. An elderly person walking across a soft landscape moves differently from someone who exercises regularly. So you are, in a way, staging a negative prosthesis. You’re doing something with the space that suggests a theatre event.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] During a rehearsal with dancers I once asked them what it was they were doing, and why. One of them said: »The space tells me what to do.« At first I thought that was nonsense, but then I decided to take that verbatim. »1st Part Conditional« represents an attempt along those lines; I took odd mannerisms, like children for example have, and transferred them onto clothing, furniture and the space. They are demanding and they don’t just caress you, they pinch you, too.

[b]Schöllhammer:[/b] This sort of sculpturally staging a space and striding across a room also play a role in your exhibition with Yvon Lambert.

[b]Schinwald:[/b] Yes, I more or less built in hurdles; you have to duck, or climb over things. I took the idea in part from how people in Japanese homes deal with the body. Confronted with a low threshold, people lower their heads in a submissive gesture – so space is by no means just passive, it is quite a bit more.

Translated by Jennifer Taylor-Gaida