Issue 4/2010 - Politisches Design

Gérard Gasiorowski

An imaginary museum of conflicts. And a constant series of new questions.

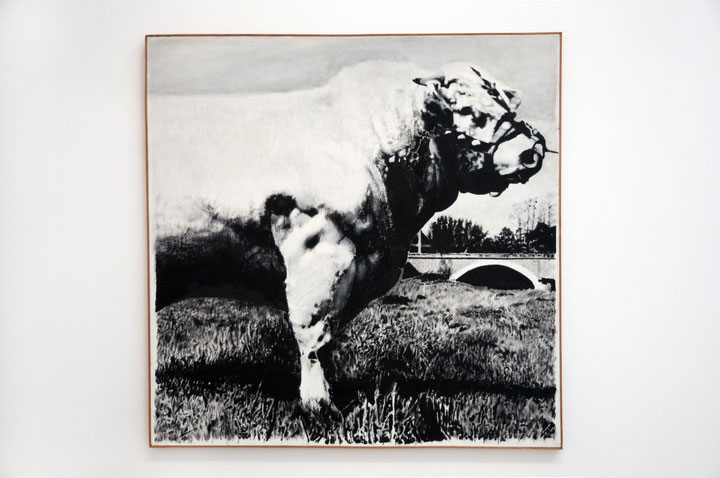

The motto »Re-Start – Starting the Painting Again«1 by Gérard Gasiorowski articulates the active, and not just historical, rivalry between photography and painting. The technical innovations of photography also brought about a revaluation of the idea of reproduction. Gérard Gasiorowski (1930-1986) developed a form of art history that was tailored to his own person, one dominated by systemic changes and polymorphisms. He was very much influenced by reading Elie Faure’s »Histoire de l’art« (1919-1921), to which his attention was drawn in Paris by a text by Henry Miller. He ironically called the action of painting the cover of the paperback, which he always carried with him, »fingering«. As late as 1986, he was still calling it »his bible«. He also constantly questioned art history. He began at first with a so-called photo-realism (in the »The Approach« series, 1965-1970), paintings full of vivid contour covered by a kind of photographic black-and-white glaze, behind which »the trace of the brush« took the back seat. Other phases display a mixture of individual mythology with conceptual art based on institutional critique. In between, there are meditations and, again and again, in keeping with the times, a serial kind of intermediality in various periods, here unmentioned. In the last phase, which was dedicated to abstraction, the artist broke with his initial photo-realism. He tried to translate a disparate body of knowledge about planar application of colour that he had intuitively learnt from the Lascaux cave paintings, Giotto, Rembrandt, Cézanne, Manet and others into a 20th-century language adequate to himself. He now no longer suffered from a mistrust of painting. At the end, he wanted to paint – without photographic apparatuses, without being fixed on reproductive visual media.

It is striking that these phases did not run in a linear fashion, but were often simultaneous or parallel. His position reveals contradictions in social techniques, so to speak the »habitus« of Pierre Bourdieu that is attributed grosso modo to artists: seriousness, irony, playfulness, elitism, asceticism, eccentricity, rebellion and numerous passionate, transgressive excesses. Gérard Gasiorowski undertook experiments in analytically found roles. He researched their languages extensively. For example, from 1975-1982, as homo ludens, he gave himself a fictitious identity as »Worosiskiga« (anagram of the name Gasiorowski) when he founded the Académie Worosis Kiga (A. W. K.). On the instructions of the fascist, authoritarian Professor Arne Hammer, whom he fabricated, all the pupils had to try and paint a hat: every year, four years long. This attack was directed at the celebration of the canon of great names handed down in theory and practice. Four hundred realistically painted hats were done, with labels bearing 100 artist’s names such as Acconci, Boltanski, Buren, Cadéré, Kounellis, Marden, Motherwell, Warhol and many others. Gérard Gasiorowski, who acted the role of the tyrannical director but also supervised the project in a neutral capacity, revealed institutional rules by signing the works of rejected pupils. In kleptomaniac fashion. He invented medals and rules for the academy, and kept files on expulsions and bad behaviour.

The hat became the emblem of the struggle for power and mastery: to a symbol for the illusionary glorification of the unique »genius« of artistic personalities. All hats were photo-realistic grey-in-grey paintings. In the meantime, Gerhard Richter was also creating his grey-in-grey paintings. Afterwards, Gasiorowski posed for a photo wearing a cheerful hat with a red ribbon with white dots, sure of victory, clever, in front of the serial wall of mouse-grey hats that pupils had to paint by order. He mixed upthe name labels »underhandedly«.

Here, the criticism does not lie quotably on the surface of the artistic activity, the habitus, but in the folds, between the lines of his theory – and a new practice. Gérard Gasiorowski thought very precisely, but had also realised that there was little sense in thinking about »power« in art history as a centre. His attacks were subtle, not frontal. He circumscribed, unfolded and broke things down. He was aware of working in a social field.

His vivid imagination finally had the academy fall in a student revolt. After this, he used drag, rites, and even the invention of a language to undertake changing the identity of his gender. It was four years during which he hid from public view and refused to exhibit. Before this, as the American Indian Kiga – the outsider of the academy – he bumped off the professor, but also became Kiga, who painted with his excrement, as with transparent juice. Symbolic pictures of everyday commodities, houses, birds and plants were created. It was about a methodical regression as survival amongst excess. In waste. In stench. About finding artistic material where others are ashamed and make its name taboo. To define the great rent in the artist’s desire, it is enough to compare the birds painted with the juice and the military objects.

Beginnings of photography critique

In the 1970s, a whole ten years after Gérard Gasiorowski’s photo-realist paintings were created, there was still no photography critique in France. At first, various critics in daily newspapers - »Figaro« (1969), »Le Monde« (1977) and »Libération« (1978) – started slowly building up this discipline. When Jack Lang entered the Ministry of Clture in 1981, this cultural field changed. Through institutionalisation on a grand scale, he elevated photography, as a medium that combines art and modern technology in a variety of ways, to a matter of national significance and deliberately established it as part of middle-class taste: as a medium that abolished »the borders between culture and the public sphere« on the basis of taste.2 It was not until 1980 that Roland Barthes’ »La chamber claire« and cross-references to Michel Foucault’s texts led to the establishment of a critical theory of photography.

The lack of a precise photographic theory influenced the way people wrote about Gérard Gasiorowksi’s pictures: imprecisely. One consequence was that the transformations between photography and painting were barely researched. They were not named. Nonetheless, there was explicit rivalry, especially because the gaps in photographic theory were filled by texts on photography that, as Bernard Lamarache-Vadel vehemently criticised, were simply written in imitation of the jargon of painting criticism. Especially because Gérard Gasiorowski’s »Musée imaginaire« really left us no requiem to traditional painting –he left behind the hope for an egalitarian relationship between the media like a legacy.

Large series of flowers – blossoming and wilting – (which he looked after and kept under daily observation), on the A.W.K. academy, broad cycles on war and the object montages on the »violation of painting« were all created simultaneously. Michel Enrici wrote: »The desire to paint however loses its cynicism, and therefore no longer needs to compete with modernity nor with the history of aesthetics […] A white space always appears between flowers and pots […] But flowers and pots always appear as a delimitation of the sign and painting. […] There is also a barely perceptible contrast between colour and nuance […] Attentive to everything that connects him with the world and the existential reality of the objects, he doesn’t interrupt this series until 1982, when the paper supply allotted for this purpose runs out.«3

The huge cycle »War of 1974« (1974-1983) is a large ensemble made up of almost 60 very different parts. These are also signs on a white background. But intellectual negligence in the reception of this work creates unease, in view of the photo-realistic transformation of painting. Even though 1974 was the year before the end of the Vietnam War, and thus a tragic one in global politics – in the USA and Europe, there were civil rights movements and student protests in the streets of big cities -, the known critical literature on the cycle treats the facts with absolute historical nonchalance. In the texts, metaphors blur as if joggled about on a rough track. The title and date of this cycle, which is defined by the symbolic accumulation of war-related objects, are not referred back to any real war. This is a serious omission. At the most, the year 1974 is classed as a »war of life« for the artist. As a »war against art«?

But three times, an abstract logo is the central point of the wide-ranging multi-media installation »War of 1974«, which was executed contrapuntally in the media photograph/painting/object: the Tricolour, France’s state flag – bleu-blanc-rouge; nationality as a fluttering abstractum. The design of a flag. In one picture it is burning. Is that so very insignificant? Small pictures, as if punched out of the instant. Full of dross. Full of black patches. Back then, there was a Cold War …

What we do not know: Does this emblem symbolically evoke the occupation of Vietnam by the French colonial power in the 1940s?4 How do the lines and myths of power run? First of all: they are present.

The work of Gérard Gasiorowski does not simply steer towards »painting«, as one can so often see written with glib charm today. Only in the paintings of his last years is there an explicit retraction of the experience of painting »violated« in its historical materiality. Vehement discourses between the artistic procedures – something Gérard Gasiorowski thematicised in no uncertain terms – brought about a constant polarisation back then, a kind of competition in the European and US art scenes. The conflicts also occurred between these scenes – we can recall what fights there were between »abstract« and »representational«; what fights happened between the genres, the attitudes, the terms, the vocabularies.

In the context of »War of 1974«, there is a small, mounted photographic sheet consisting of 36 pictures (photos: Claude Caroly) that also draws on military emblems. Here, Gasiorowski »plays« at war, as a kind of »soldier of art« 5 (Michel Enrici). An explanation like this must come about if we understand art as »territory«, as an area defined by a simple ideology, as a space of representation that is defended against other spaces. In the large wall installation mentioned above, there are crashing military planes, trucks, armed soldiers in ambush, concrete camouflage colours – khaki, beige, yellow, grey. The action in the small photo tableau, however, is artistically guided by the arranger, who »only« plays this out using dirt cheap props in the studio. In the penultimate line, a cat looms large. Dominating the picture to the point of dissolution: Gasiorowski and Marie-Claude Charel appear at the end peacefully united as a couple.

We can no longer ask the artist how often he allowed his trauma, the experience of seeing his father killed by soldiers while fleeing in 1940, to recur. He died of a heart attack at the age of 56. He kept pace with our time in his art and experienced all the contradictions of the art market.

Carré d’Art – Musée d’art contemporain de Nîmes, 19 May to 19 September 2010: catalogue published by Hatje-Cantz, Ostfildern 2010.

Translated by Timothy Jones

1 Gérard Gasiorowski, Starting the Painting Again, Carré d’Art – Musée d’art contemporain de Nîmes, 2010.

2 See Marie Gautier, Bernard Lamarche-Vadel – Critique de Photograhie: Une Alternative à l’Institutionalisation du Médium en France in Dans l’Oeil du Critique. Bernard Lamarche-Vadel et les Artistes, Paris, 2009

3 Michel Enrici in Gasiorwoski Peinture, Adrien Maeght (ed), Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1983.

4 To be precise, since the end of the 19th century.

5 See Michel Enrici, ibid.