We live in a moment of uncertain beliefs, economic and climatic catastrophes, where institutions take possession of the discourses of activist movements, making difficult to elucidate the reasons and interests that underlie certain politics turning more confusing our capacity of “seeing”.

These are not minor questions when we try to articulate different conceptions of art and politics involving ourselves in the search of new “ways of doing “out of hegemonic mandates. Debates and doubts arise when we ask ourselves about the function of art in the pretension that what political art proposes does not remain reduced into an instrumental question or into the paradigm of a sterile formalism.

We started, in the 60s, with the idea that our work could be known. We faced a cultural context that only propped the status quo we were opposed to and confronted with our productions.

We thought that the historical moment we were living in demanded to subvert the art field and make the existing definitions collapse. We learnt out of practice that it was possible to think about a different project where to appeal new publics through experimental ways of doing art producing displacements and the exceeding of limits in the art field.

We thought about streets and other alternative spaces potentially alive where to reactivate dialogue to produce decentralization processes. We believed that ethics and aesthetics should be articulated and be the basis for art practice. The poetic-political works we started developing were born through the search of new languages linked to the historical circumstances we were living in. Conditions that later drove us to abandon art and take compromise and militance as actions that would generate a new social conception.

As a group we were able to think about aesthetics and politics articulated in praxis. Experience transformed us producing deep changes in our subjectivities starting from an artistic practice that put into action the breaking of conventions and thought production as a living lab where we could experiment emancipatory ways of life. Challenges so as to create a space where art could assemble political learning and subjectivity.

Actions that adjusted an imaginary and a way of doing that involved us as subjects and as artists where we tried to modify the ways of production and distribution of our works and also the relation with the public, conceiving reception as a collective participation instance. This politization was not restricted to contents renovation but to the transformation of language and our participation as regards social conflicts.

Within the group we learned and constructed an autonomous thinking based on knowledges and experiences of each of us. In the heat of discussions and debates and in the frenzy of ongoing events, artistic practice built us as subjects.

That imaginary was quickly destroyed. In the 70s our countries were subjected to totalitarian military regimes that responded to other values and interests.

[b]Our present is different from the 60s and 70s[/b]

As numerous archives in different Latin American countries are becoming visible relations and circumstances appear that reflect a common character among them. Materials, documents, photographs, that were kept and preserved by some of the protagonists. Traces of a past not so far away, belonging to collective and group works of artists that took part in moments of repressive and dictatorial regimes. Documents that in many cases, are actually the only ones at hand, experiences that were hidden or ignored for a long time.

Archives that were very often built as a record of a personal experience that for years had been ignored and they become now unique reference because other sources were destroyed, burnt, stigmatized or were turned “invisible”.

The archive is thus constituted in a place of articulation of artistic- political experiences of collective works and the personal and affective motives which made their preservation possible. Between the notion of work of art and that of the document, there is in the limit of both concepts as artistic practice.

In last years there has been an interest in the 60s-70s productions, coming from the hegemonic centers, interest that lots of times works as an excuse to implement appropriation and spoliation.

In art institutions certain concepts that previously had no visibility now hold a privileged place. Practices that were hushed or interrupted by dictatorial regimes now circulate in the market stripped from their critical potential. These practices are neutralized under the category of political art that homogenizes and erases the singularity of processes and contexts and force us to try actions in opposition to these aestheticizing appropriations.

In our countries where politics of preservation and socialization of archives are almost non existent we face the need of protecting and reactivate the critical political potential of these experiences.

The preservation of archives defy us as regards thinking about different politics of ways of experimenting and access to culture, politics that help value these archives and avoid the escape of cultural patrimonies to central countries as the only possibility for their preservation.

I started to gather newspaper and magazine articles in a spontaneous way, searching – maybe subconsciously – for a reaffirmation of what we were doing.

I began to compile material from the group that would later give birth to a collective which, by the end of 1967, would adopt a new dynamic as it assumed an organic shape and its members gradually took on different responsibilities and tasks.

There is also another source feeding this compilation of documents, the contribution of Carlos Militello, who was the photographer within the group. He recorded most of the exhibitions and actions carried out by the group. He kept those negatives and archived them which allowed the preservation of the originals.

This is how a body of publications, press articles and photographs were preserved – an assemblage that kept on growing even after the group had dissolved.

During the last dictatorship, when people were impelled to get rid of their books and emptied their libraries, buried documents or burned papers, Carlos and I still kept the documents that constitute the history of this group, which was really significant for me.

All those documents, together with a great quantity of books, were left in my parents’ house – where I lived during the 60s –scattered in various places.

During the following years I kept on re-collecting papers. I had a growing interest in social issues related to repression, torture, the situation in Latin America.

Those were difficult years. The terror of those days gets mixed in my memory with friends’ disappearances and the offensive actions carried out in people’s homes.

We felt a paralysing fear. I was anxious about not compromising or exposing others, even at a moment when the group no longer existed and, under certain circumstances, the situation forced me to adopt different criteria of preservation to protect persons even if this meant destroying documents. The criteria I finally adopted meant I would only keep the material which had already been made public. I kept this and destroyed, amongst other things, the notebook with minutes of our meetings and information about the debates and discussions that had taken place within the group.

With the advent of democracy in 1983, the first questions about the avant-garde events of the 60s were posed and interest in them began to grow.

During the mid 90s, many people consulted this material and use or reproduce it. At the beginning of this process I would not keep track of who was taking the material, what was being taken, or whether they gave the documents back, and consequently some documents were lost.

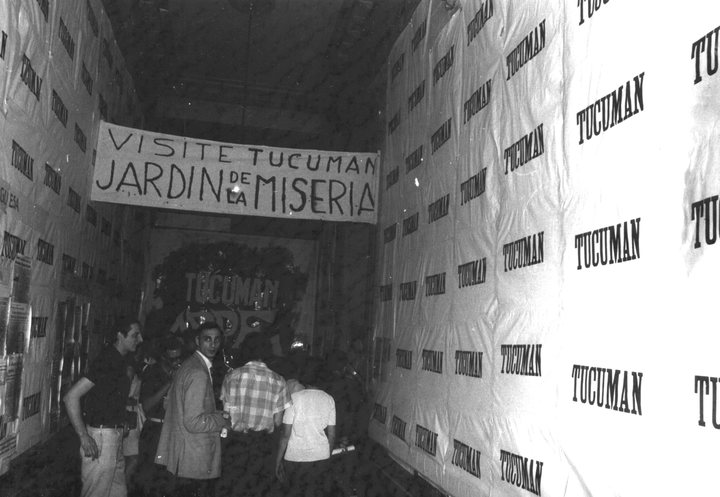

Some negatives from Tucumán Arde had been lost for a long time until, very recently, I found them camouflaged among other negatives and slides from trips and other family pictures while films and type recordings were never found.

What an archive is?

When is it completed?

How and from where is it interrogated?

What is the sense to exhibit or publish an archive?

How to get near to the preoccupations and thoughts they stand for?

Images and texts, old newspapers, photographs, yellowish and fragile papers kept in plastic sheets, vibrating when we go through them. Utopias, desires, illusions, resistance, anger, debates, differences… Group encounters, the itinerary travelled and the separation.

This archive represents the memory of some of the experiences of a group of artists of different ages and trajectories. They are documents mainly brought together during 1967 and 1968 that shed light on a moment of our history and on the work produced by a group moved by the circumstances affecting the place in which it was living.

It is related to a short but profound process during which our searches were inspired by what involved us as subjects and as artists; it belongs to a time when art became the meaning of life. I could describe it as a period of such intensity that living itself had become an aesthetic experience.

This archive also represents one of the possible narrations on the group made by one of its protagonists. When showing it, I frequently accompany it with an account which is in fact one version of that experience, one subjective look.

There are documents and in that sense they have a certain degree of neutrality, they offer an impartial take on things even if charged with subjectivity. Therefore, they can’t be considered as an “indifferent totality of documents’, they don’t give an account of everything that happened but they are just a part of a more extensive itinerary comprising practices and discourses. It is a fragment, which, nevertheless, became by historical circumstances into the most significant group of documents that exists today in relation to this process of artistic radicalisation.

They provide the basis to narratives which will vary according to the way in which they are considered and questioned. This allows us to reflect on the multiple interpretations to which Tucumán Arde and the group’s itinerary have been subjected. We may as well say that this isn’t naïve or accidental. It has to do with the way in which we dive into history and make it visible.

Throughout all these years, I have continued to add documents to this archive: documents from that time that someone might bring to me, as well as new texts, reflections, interpretations and readings that are published and that prevent the archive from being something finished or complete, because new and additional relationships are established, and it becomes harder to define its limits.

Time has made the archive what it is today. While it exhibits its presence, it also displays the marks left by absences, the processes of censorship, the suppression of information, and other losses.

For years I kept papers in an eclectic way. Several times I intended to put order in them, but the initial order collapsed while papers piled up on tables leaving no free space. On other occasions I tried different classifications and organizations of these materials but with time my interests changed together with my conceptual approaches thus papers and documents that were discarded very often acquired renewed interest and it was necessary to incorporate them into files and boxes.

With time this amount of documents began to be known and the demand for materials changed for petitions to come to consult them. In this way it acquired public status.

Keeping the archive involved a responsibility. It also causes conflicts and contradictions.

The task of maintaining and preserving an archive, to then mount and display it leads necessarily to discussions of different topics inherent to methodologies, strategies and ways of thinking about history and art.

During these last years I have been invited to present the archive in different events and circumstances. Each experience to show the archive is a challenge. What to show, how and where are questions that change according to context.

The set up is significant and in this sense it can facilitate questions or stand as a model.

What and how we exhibit has to do with ethic and politics so each presentation becomes a critical action.

To exhibit certain types of experiences that have occurred outside museums and art institutions opens possibilities of thinking another kind of institutions, another concept of museums, another ways of showing that would built a new

concept of public away from hegemonic formats.

The archive let us establish genealogies with actual events and lines of thoughts and research that tend to analyse art and the artist from other perspective from that of the market to reassure the critical value of artistic practice and as instrument for process of subjectivation and intervention in the social context.

Archives are texts, each document having several levels of significance.

Context provokes different readings and interpretations.

The organization and the exhibition of an archive is a construction, a question of edition and montage. The way it is shown is important.

The compromise with the archive does not deal only with the past but with a necessity in the present to reflect on actual practices.

An archive is an open space to be investigated and interrogated. It is not a corpse or a ruin

It put to circulate new voices. It challenges us to decolonize our ways of thinking and invites us to reformulate our own histories producing multiple narrations and articulating other maps of relations.

To exhibit an archive is to reactivate and also to reinvent it remembering us there is no unique truth.

The archives of artistic practices explicitly bonded to their social contexts allow get to know and investigate a variety of expressions and actions. Such documents imply the possibility of constructing other readings and critical recuperations from different points of view of the present times. Articulated interpretations that re-actualize experiences and debates, thinking and actions which originated in contexts and concerns that seem distant but nevertheless echo here and now.

The memory of sensible experience of artistic practices that cannot be reduced to its own materiality prompts the need to recreate new ways of socializing this legacy if we want to reactivate its poetical-disruptive possibility of new processes of subjectivity..

How do we think today about new practices from which other ways and other stories could be understood in relation to multiple productions opposing schematic and simplified concepts about art and politics?