In the historic period in the focus of attention of the conference on the theme of Avant-Gardes from the Decline of Modernism to the Rise of Globalisation 1956-1986, and Contextualizing Post-War Avant-Gardes, Vienna 2010, among events in the ex-Yugoslav art space of special interest is a series of five exhibitions organized by the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb according to the following dates and exact titles: New Tendencies, 1961, New Tendencies 2, 1963, New Tendency 3, 1965, Tendencies 4, 1968-69, Tendencies 5, 1973. Considering that they were held in the time period exceeding a decade, it is understandable that these exhibitions, from the first to the last, presented diverse artistic productions that may be designated with terms such as neoconcretism, neoconstructivism, programmed art (arte programmata), gestalt research (ricerca gestaldica) kinetic and luminokinetic art, computer-generated visual research, conceptual art - art phenomena which may be legitimately jointly subsumed under the group term Post-War Avant-Gardes. Here it is worth mentioning that thanks to this term, on the occasion of the exhibition of Arte programmata e cinetica 1953-1963, organized in Milan in 1983-84 by Lea Vergine, involving the first historization of the said artistic phenomenon, the concept "Ultimate Avant-Garde" (L'ultima avanguardia)1 was introduced. The whole complex of the five Zagreb exhibitions that are to be embraced here under the unifying title New Tendencies, from the moment of their commencement onwards, arose considerable attention for numerous reasons: namely, how these exhibitions came about from the organizational and conceptual view, how come they were held in the then socialist Yugoslavia, what was their international and local cultural and historical context; finally, what this whole phenomenon may mean today, how it is to be understood and assessed, what it contributes to common European art of the second half of the Twentieth Century.

[b]"A Surprise Case"[/b]

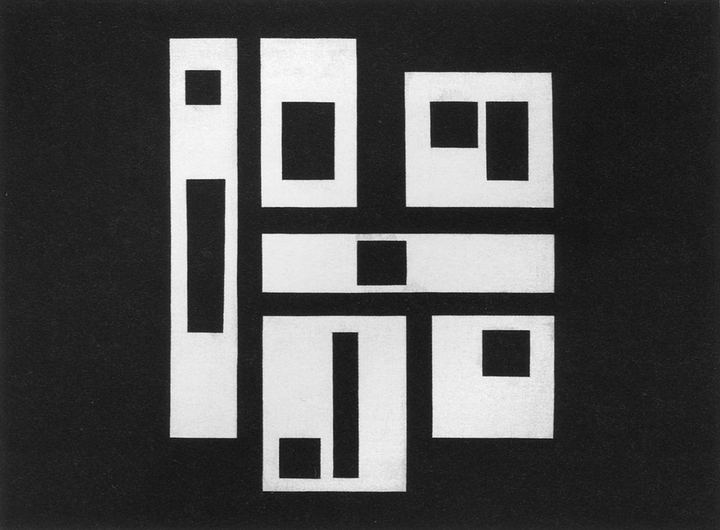

An answer to the question as to how the first Zagreb exhibition New Tendencies 1961 actually happened, at a first glance is resolved as a case of an almost accidental coincidence. Namely, in the summer of 1960, on his journey through Yugoslavia, German artist of Brazilian origin, Almir Mavignier, visited Zagreb and in an unplanned meeting with the director, curators and associates of the Gallery of Contemporary Art proposed to the hosts an international exhibition to be held of then current art events. This proposal was enthusiastically accepted by the hosts and thanks to their organizational skill, the concept of such exhibition was soon realized and it included the following artists: Manzoni and Castellani from the Milan Group Azimuth, Mack, Piene, Uecker from the Dusseldorf Group Zero, Italian Group N from Padua and T from Milan, Paris Groupe de recherche d'art visuel, individuals such as Dorazio, Morellet, Pohl, Talman, Adrian, Gerstner, von Graevenitz, Dieter Roth, Mavignier himself, and croatian artists Knifer and Picelj. The title of the exhibition New Tendencies was also suggested by Mavignier as a shortened version of the exhibition Strictness – New German Tendencies (Strigenz – nuove tendenze tedesche) held at the Pagani Gallery in Milan in 1959. In his subsequent remembrances Mavignier was to testify the following on this event: "The greatest surprise of the first exhibition New Tendencies was astonishing similarity of experiments by artists from most diverse countries, although these artists knew little about each other or often even did not know each other. That phenomenon in Zagreb for the first time made us aware of the existence of an international movement in which art reveals a new conception that experiments with optical research of surface, structure and objects".2 That this initiative indeed was timely started, that later on it lived up to see durable historic confirmation is witnessed, among other things, by the fact that the first Zagreb New Tendencies exhibition was included among key art events in Europe in 1961, together with exhibitions Bewogen Beweging in Amsterdam's Stedelijk Museum, later on transferred to Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Le Nouveau Réalisme à Paris et à New York and A 40⁰ au-dessus de Dada, both in Paris and group Zero in Düsseldorf.3

[b]Continuity in the Art of Constructivist Approach[/b]

However, the fact that it was in Zagreb in 1961 that the first exhibition New Tendencies took place, still was not, as it seemed to its immediate initiator Alvin Mavignier, just a single "surprise case". Indeed, Mavignier gave the exhibition's organizer the necessary impetus, but the then Zagreb art climate had been already greatly prepared for by previous events and contributions of numerous artists and critics from the home milieu. Namely, that in the early Sixties was possible to establish a continuity in the "Art of Constructivist Approach" is the merit of the existence of the group EXAT-51 - New Tendencies in the early Fifties: because, the connection EXAT-51 - New Tendencies in addition to being personal (as many as four members participated in both of these formations); that connection is both conceptional, and in the last instance also ideological. Going even deeper into historical past it is worth remembering that in the early Twenties Zenit magazine was published in Zagreb, which systematically included textual and illustrated contributions of Russian and East-European constructivist avant-garde (Maljevič, Tatlin, El Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Moholy-Nagy, Kassak, Taige). The persons who helped the first exhibition New Tendencies to be organized in Zagreb were not only acquainted with this entire heritage, but had been culturally and conceptualy educated on it. When the liberal cultural and political circumstances of the early Sixties in the socialist Yugoslavia provided possibilities for independent activity, these persons commenced their tasks with the following vision: gather in their midst a new avant-garde of the "Art of Constructivist Approach", in order to at least minimize devastating consequences of that policy which in the Soviet Union crushed the pioneer suprematist and constructivist historical avant-garde. In other words, the organizers of the first Zagreb New Tendencies exhibition thought that factually only in the socialist Yugoslavia it was possible to revive the ideational legacy of the historical constructivist avant-garde, of course in accordance with the changed political environment of the post-war Europe and in different forms of expression. It was just that, and not some no matter how fruitful "surprise case", which was the fundamental guiding thought of the most meritorious organizational actors of the first exhibition New Tendencies in Zagreb in 1961. These were, beside the artists Knifer and Picelj, the director of the Gallery of Contemporary Art Božo Bek, and the critics Radoslav Putar and Matko Meštrović. They were joined at the second exhibition New Tendencies in 1963 by Vojin Bakić, Vlado Kristl, Vjenceslav Richter, Aleksandar Srnec and Miroslav Šutej, who completed and reinforced the team of domestic artists.

[b]Toward the Rise and Fall of the Homogenous International Art Movement[/b]

The time between the first and the second exhibition New Tendencies 1961-1963 was a stormy period of inner organizational and ideational turmoil resulting from the efforts of numerous agile actors to found, on the foundations of positive and encouraging experiences of the first Zagreb exhibition, a personally, linguistically and ideologically as firmly connected as possible, an international art movement. Witnesses Manfredo Massironi from the Padua-based group N: "The most important event in 1963 undoubtedly is the second exhibition of New Tendencies. It is primarily characterized by the rigorous selection of participants, and then by difficult search for a common ground of understanding, in order that a great and unique international movement could be created". A well-known and specifically indicative among the documents from the archives of the history of New Tendencies is the one confirming that immediately after the second Zagreb exhibition the movement was renamed Nouvelle Tendence – recherche continuelle (New Tendencies – Continuous Research), while a body calling itself Coordinating Committee consisting of Gerhard von Graevenitz, Julio le Parc, Enzo Mari and Matko Meštrović undertook the selection of future members of this movement, excluding from it, allegedly for non-complying with a standard model, for insufficiently orthodox views such as, according to them, were manifested by Adrian, Bakić, Cruz-Diez, Dorazio, Knifer, Mack, Piene, Uecker, Srnec, Šutej. On the theoretical plane of canonical importance for the phisionomy of the movement is a text by Matko Meštrović under the characteristic title The Ideology of the New Tendencies, published in the catalogue of the second Zagreb exhibition 1963.5 The turmoil within the "hard core" of the newly established movement continued at the conference in Verucchio in September of that year with extremist view of Le Parc from the Paris-based Groupe de recherche d'art visuel. Oscillations of mood inside that "hard core" within a relatively short time period between the first and third Zagreb exhibitions 1961-1965, in a sincere and heightened tone of voice, were described by Massironi: "In theoretical assumptions of the first New Tendencies exhibition, doubts were to come only later on and actually this third exhibition is all based on doubts that we did not want or could not have, on insecurities that we rejected, and also a little on the exhaustion to which we succumbed when looking around us we saw progressive decline, hopeless mediocrity and rapid ruin that marks any intellectual decline taking place within the capitalist society. The exhibition The Responsive Eye in the Museum of Modern Art in New York is the best example for it".6

[b]From Constructivist to Computer-Generated and Conceptual Art[/b]

Above mentioned New York exhibition of 1965 incites controversial feelings among participants of the New Tendencies movement: while, for example, on the one hand Mavignier claimed that "at the opening of this great exhibition, which could be called historical, he had to think with gratitude of the contribution provided to that exhibition by Zagreb"7, the uncompromising and politically distinct new-left wing advocate Massironi saw in that exhibition nothing else but a manoeuvre of the American museum and market system to launch not long after pop-art another art phenomenon of similar letter and excuse – op-art, labelling this whole operation, as far as the New Tendencies are concerned, a "Pyrrhic victory" and a "first-class funeral ceremony".8

In August of the same year the third Zagreb exhibition was held, now entitled in the singular New Tendency in an atmosphere of scepticism, doubts, uncertainties, unfulfilled expectations. In the introductory text to the catalogue of this exhibition this situation was described with a lot of self-criticism by Meštrović: "The crisis broke out particularly on the plane of organization that at a certain moment was turned to the forming of a firm international movement, but it was immediately clear that the causes of this crisis were not of organizational nature. Basic ideational values the bearing capacity of which initially seemed to be almost unlimited and which by its historical projection greatly surpassed such practical changes however became suddenly relativized". And further on in the same text: "The danger was equally hidden in the corrosive and corruptive activity of fundamental material forces that govern the world determining its curved path; and these forces are not foreseen. In the law of capital every illusion is permanent and effective until it is bought or until its magnetic field brings disturbance into ideational intentions. And they appeared in the time and society in which that influence was not possible to avoid".9

However, the third Zagreb exhibition brought to the movement also some important refreshments, particularly visible through the participation of American non-commercial art community under the characteristic name Anonima Group and Soviet dissident group Dvizheniye led by Lev Nusberg. Certainly, such meeting actually could have only taken place on the soil of non-aligned Yugoslavia. This fact has once more proved the advantage of this terrain "between West and East", which in other words means that concrete socio-political context in which international New Tendencies exhibitions had taken a firm root. And whereas in other countries of Europe the élan of community spirit among members of the movement was gradually but irreversibly slackening (thus, for instance, the award of the Grand Prix at the Venice Biennial 1966 to Le Parc for his participation in the pavilion of his fatherland Argentina sped up the breakup of the Paris Group de recherche d'art visuel), the series of Zagreb exhibitions continued to renew itself by the fourth, one of the first in the world dedicated to application of computer technologies in the area of visual research in 1968,10 (the same year when the exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity was held in London) and the fifth in 1973 with which they are redirected towards arte povera and conceptual art, gathering pioneering authors such as Anselmo, Kounellis, Paolini, Penone, Buren, LeWitt, Huebler, Baldessari, Flanagan, Latham, On Kawara, and domestic artists Dimitrijević, Trbuljak, Damnjan, Šoškić, Matković, Szombathy, Szalma, Kerekes. However, with this they cross over to a considerably changed problem area, with such their concept and makeup of the artists, the previous basic orientation of the New Tendencies exhibitions toward the "Art of Constructivist Approach" was coming to its historic end.11

[b]Inside and Outside of "Socialist Modernism"[/b]

The series of the five Zagreb New Tendencies exhibitions initiated and held in the political, cultural and artistic context of Socialist Yugoslavia is inseparable from that context; as such, it was only possible precisely in that context, although even there it was an exceptional and atypical case. With the political rupture with the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc countries in 1948, Yugoslavia abandoned current ruling ideologies of socialist realism in culture and art. The reorientation of its foreign policy made possible for Yugoslav art scene to open up to the West, primarily to Paris that, like in the period between the two Wars, became the most frequent place of temporary or permanent stays, exhibitions, acceptance of art poetics of majority of members of the first post-war generation. No doubt, then, that it was for political reasons, although the decisive factor was the personal efforts and results of the artists themselves, that the rejected socialist realism gradually was being replaced with the next dominant art formation, which because of specific social circumstances in which it was created , may carry adequate name of "socialist modernism". In this, under the term "socialist modernism" was not understood any specific art style or language, but rather a whole highly complex institutional-educational-productive "art system" that had and used material, personnel and media support of the ruling policy. As such, that system was organizationally supervised by appropriate ruling forums, but at the same time in its internal functioning was flexible and liberal enough and thus bearable and acceptable to most artists. The result was that within the system unfolded entire artistic life of the second post-war Yugoslavia.

However, with time it was shown that precisely such a system was suitable to lukewarm and non-stimulating climate of artistic mediocrities, that it generated renewal of inter-war expressive languages and mentality of bourgeois intimism in a seemingly new clothing, which all resulted in a very widespread phenomenon of moderate late modernistic, primarily painterly versions and variants that in domestic theory and criticism were labelled "socialist aestheticism". According to interpretations of this phenomenon, "socialist aestheticism" was quantitatively prevailing and precisely for being apolitical, it became the most acceptable art idiom to the ruling politics of the socialist Yugoslavia. However, outside of its field of influence remained and unfolded rare bolder and more radical breakthroughs certainly the most relevant among which was precisely the series of the five Zagreb New Tendencies exhibitions between 1961 and 1973.

The Zagreb New Tendencies were initiated and accepted in a narrow circle of theoreticians, art historians and art critics of fundamental pro-Marxist formation; they gathered artists politically progressive, but not of declaratively pro-Communist orientation, all of them together primarily as self-conscious and liberal-minded individuals rather than as firm adherents of the ruling social order. In the total system of "socialist modernism" they were distinct minority at the very margin of social support, yet still sufficient for the Zagreb exhibition to ensure its periodic and constant life, as long as they themselves were able to provide vital and topical ideas. The Zagreb New Tendencies are one of the areas of aspiration of those domestic art circles devoted to the idea and realization of "socialism with a human face" under specific Yugoslav circumstances, in which in principle they were similar to the Zagreb branch of Praxis philosophy. For their attitudes and undertakings they looked for understanding and support among like-minded people on both sides of the border erected by the block division of Europe in the time of the Cold War, and especially in the European West among members and sympathizers of the new left in radical art groups in the New Tendencies movement. That these circles of the Zagreb exhibition were considered important also for their own strategic goals was testified by their frequent visits to Croatia and Yugoslavia, socializing and collaboration with domestic artists, in the conviction that they also were participating here in a far-reaching social process of democratization and emancipation, which was the aspiration in the circles of politically radically oriented participants of this international art movement. In the artistic climate "after the Informel" (dopo l'informale, oltre l'informale) in which, after the first post-war decade marked by existential pessimism was felt the élan of intellectual and material renewal, the New Tendencies express precisely such positive constructive epoch-making mood. Already at the time of their rise, in 1963 Meštrović condensed and summarized the essential intentions of the New Tendencies in his following assessment which is basically still valid today: "The New Tendencies appeared spontaneously in that climate which was felt first by the old Europe. Positive attitude toward scientific knowledge is the tradition of the pioneers of modern architecture, neoplastic artists, Bauhaus artists, which although did not live up to its fullness, still remained alive. Still alive was also the confidence in potential transformational power of technique and industrialization, while the deep-rooted thought of Marxian science enabled a constructive approach to social changes and problems. That is why it was possible in Europe a first criticism and first opposition to components of corruption and alienation and decisive demand for demystification of the notion of art and artistic creation, for debunking of the dominating influence of art market that speculates in art, treating it contradictorily both as a myth and as a commodity. The aspiration to overcome individualism and the spirit of collective work was also possible; progressive political orientation was distinctly expressed, while the issues of art was focused not on the question of uniqueness of artworks but on the plastic and visual exploration with the objective to determine objective psycho-physical bases of the plastic phenomenon and visual perception, precluding thus any possibility of the involvement of subjectivism, individualism and romanticism, with which all traditionalist aesthetics were burdened".12

What were the real effects of these endeavours and undertakings, what was in them achieved and what was missed, what was in the objectives of the New Tendencies realistic and what aimed too high, how much was historically possible in it and how much utopian, remains for present-day and future analyses and evaluations. However, the fact is that the New Tendencies, as they were recently assessed and estimated at the retrospective exhibitions in Ingolstadt and Graz 2006-2007 and Karlsruhe 2009, conceived in the political and social circumstances of socialist Yugoslavia, wrote one of the most exciting chapters in the whole of European art history in the second half of the 20th Century seems to be and remains absolutely undeniable.

Translated by Petar Vujcin

1 Lea Vergine, L'ultima avanguardia, Arte programmata e cinetica 1953-1963, Palazzo reale, Milano, November 1983-February 1984.

2 Alvin Mavignier, New Tendencies – A Surprise Case, catalogue of the exhibition Tendencies 4, Gallery of Contemporaty Art, Zagreb 1968-1969.

3 Konrad Fischer, Benjamin Buchloh, Rudi Fuchs, John Mattheson, Hans Strelow, Prospectretrospect. Europa 1946-1976, Köln 1976.

4 Manfredo Massironi, Critical Notes on the Theoretical Contributions within the New Tendencies from 1959 to 1964, catalogue of the exhibition New Tendencies 3, Gallery of Contemporaty Art, Zagreb, August-September 1965.

5 Reprinted in the book From Particular to General, Mladost, Zagreb 1967, pp. 215-224, second edition, DAF, Zagreb 2005, pp.211-219.

6 The same as Note 4.

7 The same as Note 2.

8 Manfredo Massironi, Ricerche visuali, proceedings Situazioni dell'arte contemporanea Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome 1976.

9 Matko Meštrović, The Reasons and Possibilities of Historical Awareness Raising, catalogue of the exhibition New Tendencies 3, Gallery of Contemporaty Art, Zagreb, August-September 1965.

10 With accent on the exhibition Tendencies 4, Zagreb, 1968-1969 a retrospective was organized Bit International (New) Tendencies – Computer und visuelle Forschung, Zagreb 1961-1973, Neue Galerie am Landsmuseum Joannum, Graz, April-June 2007.

11 The first historical balance of the New Tendencies was publlished at the retrospective of Die Neue Tendenzen – Eine europäische Künsterbewegung, Museum für Konkrete Kunst, Ingolstadt, September 2006 – January 2007 and in the book New Tendencies and Bit International, 1961-1973, A Little-Known Story about a Movement, a Magazine, and a Computer's Arrival in Art. Edited by Margit Rosen, ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe, Germany, the MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma., London, England, 2010.

12 The same as Note 5.