Colonial Modern, edited by Tom Avermaete, Serhat Karakayali and Marion von Osten, is a challenging and interesting publication that must, however, be ‘handled with care’. Documenting some projects designed between the 40s and the 50s by Michel Écochard, and Georges Candilis and Shadrach Woods of Atbat-Afrique - but not only - and the impact they had on the social housing or ‘habitat pour le plus grand nombre’ issue, it focuses on the role played by Colonial North Africa (essentially documented in the book by Morocco and, to some extent, Algeria) as a ‘laboratory’ for their Modernist solutions which aroused international attention and were ‘exported’ abroad. Though rich in iconographical material and texts, it delineate a picture that, like a puzzle missing some pieces, lacks the ‘long term’ historical perspective judiciously auspicated by Kobena Mercer in his contribution to the volume. Some generalized statements attribute Colonialism a more glamorous role than it had. In particular, the assertion that ‘as a result of the exodus from the countryside to cities, the colonial power in North Africa developed an architectural design for ‘large numbers’’ needs to be considered in the right perspective.

The French colonial conquest (started in 1830 in Algeria, 1881 in Tunisia, 1912 in Morocco) went along with a process of dispossession of the ‘indigenous’ more fertile and productive land that disrupted and plunged into great misery entire sectors of the rural population. When not driven to barren areas, relegated to cantonments, reclusion camps, servitude, submitted to forced conscription and labor, or obliged to emigration, they joined the urban proletariat living in highly discriminating conditions (see ‘la loi de l’indigénat’). The result of Colonialism was soon to be seen in North Africa in the growth of slums and shantytowns surrounding European harbors, factories, industrial and mining centers, quarries and new modern towns. Commenting the way Casablanca miserable Muslim dwellers ironically called their shantytown ‘Sidi Bidon Ville’, a French local paper, ‘La Vigie’, inaugurated in 1930 the word bidonville. Up to the 1930s and till the eve of independences – that is (for Algeria) almost 100/130 years after French occupation – bidonville, and not Modernist ‘architectural design for large numbers’, remained the main North Africa Colonial response to the social, economic, ethic and aesthetic problem of housing poor local population fleeing misery or whose under-paid work and hard labor was needed but had not the chance to benefit from rare housing projects or be old medina dwellers.

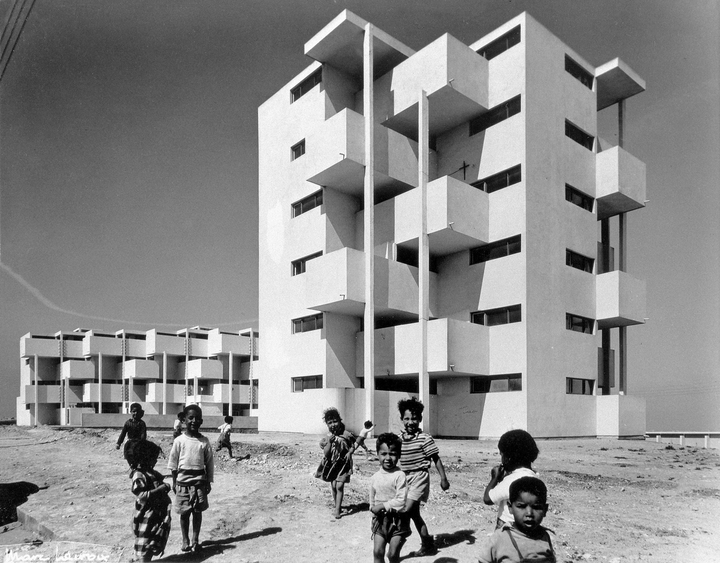

Only in the very late phase of Colonialism, and climate, during the years of intense national struggle for independence (obtained in 1956 by Morocco and Tunisia, 1962 by Algeria) Colonial authorities felt obliged to seriously consider large scale solutions for the local population. Not for modern utopia or concern for a longtime despised multitude whose minimum rights had not been in the agenda, but for bettering their own image, respond to criticism and Colonial industrial urban post-War overgrowth, and for controlling slums uprisings. In her neat historical study in Colonial Modern somehow countercurrent to some thesis of the book, Kahina Amal Djjar calls it ‘a Machiavellian strategy’. A strategy that came too late; medinas and bidonvilles were in revolt and joined the independence movement, plans ‘pour le plus grand nombre’ would in many cases remain incomplete and many bidonvilles will pass as a Colonial legacy to the independent nations.

Monique Eleb recognizes in her Colonial Modern essay that up until the early 1950s ‘the Protectorate’s only initiative in the field of social housing’ had been the Aïn Chock (Casablanca) 10.000 homes project presented as a novelty in 1944. Not brilliant for a Protectorate who had been extensively exploiting the country’s rich resources. Supported by large propaganda and crude legislation Colonialism had censured, repressed, punished North African (but not only) papers, parties, unions, persons documenting or giving voice to people’s conditions; Madeleine Bernstorff ‘s article about René Vautier’s 1950s militant films luckily sketches in Colonial Modern that part of the story, a story otherwise omitted. All the texts in Colonial Modern duly mention the unavoidable topic of Colonial time bidonvilles, yet its human dwellers, captured in old Colonial images, and the historical perception of that Colonial huge ‘other laboratory’, somehow remain trapped in long theoretical dissertations.

Fully discussed in Colonial Modern, the pioneer urban and architectural formulas of Écochard and Candilis/Atbat-Afrique group ‘pour le plus grand nombre’ deserve to be given new attention. The clue of Colonial Modern initiative - that one feels has been pursued with great commitment and keen enthusiasm - is precisely this: the presentation of that experience, its history and the documented analysis of its innovative models (we must thank however This-was-tomorrow.net and Mongiss Abdallah for introducing in all this a refreshing note on the ‘exported models’ and later vicissitudes of H.L.M. architecture). But can we speak of a North African Colonial power ‘fervidly’ developing Modernist projects to the benefit of ‘the large numbers’ without considering dates and circumstances? Young western generations who know little about Colonial history and live in times of post-modern revisionism may misinterpret some Colonial Modern broad statements as well as the elusive association it makes between Colonialism and Modernity, giving thus Colonialism credits that it does not deserve.

As a conservative system Colonialism went along with Modernization, capital investments, industrial exploitation, propaganda, acculturation, even beauty, but feared modernity as vehicle of emancipatory principles incompatible with its ideology and policy. Modernity was cosmopolitan, antithetic to ethnic based colonial hierarchy and anti-colonial (remember Breton, Éluard, Aragon distributing in 1931 in Paris the tract ‘Ne visitez pas l’Exposition Coloniale’ in support of the counter exhibition ‘La vérité sur les Colonies?’). Historical facts have still to demonstrate that ‘colonial Africa was transformed into a laboratory for Western Modernity’. Of course Modernism evolved in a world where Colonies existed and, given the role played by investments and by the myth of ‘vergin territory’, it is not surprising that it operated also, and sometimes with audacious projects, in its context.

By the time the book turns to the section called ‘Postcolonial Imaginary’, the ‘Colonial Modern’ concept, elusive as it is, has drifted to new questions that theorize the past into the present (‘Colonial Modern [exhibition] connotes this quest as a reflection of today’s search for ways of transforming regional spaces into dialogical maps’). It is difficult to see a connection between such ‘quest’ and what Colonial was (and still is) as a non dialogical map… The impression is that the words Colonial and Modern have come to mean non-historical hybrid incertitudes. The topics concerning ‘reciprocal negotiation’ and ‘contact zone’ theorized by Marion von Osten could give today some useful answers. They become less abstract when confronted with the questions raised by Colonial Modern exhibition set up in Les Abattoir of Casablanca. Yet the documents furnished on Morocco (the key area of the book) recollected in a fragmentary post-modern picturesque (oh, yes, that is Colonial…) patchwork, are insufficient. The document on the mythical autodidact filmmaker Osfour, so punctual and brilliant as it is, cannot fill the surrounding empty panorama where 50 years or more of postcolonial modern Moroccan and North African imagery remain unexplored. May be not in the exhibition, but certainly in the book. Some could observe that briefly soliciting two contemporary Maghreb artists is not enough. Others could object that it was too big an argument to develop, and that it had anyway little to do with Colonial Modern! All this, of course, is very challenging. It might also be more revealing on Western present way to deal with History (and the History of the Others) than on Africa and North Africa. In other words, Colonial Modern tells an interesting story, but not the whole one.