Today, the movement of ideas, capital and people is faster and wilder than at any point in history. Contemporary global flows are multi–directional, leaping across well–worn paths and weaving complex new patterns. In this age of mobility, no culture can exist in isolation. However, as nation–states welcome the advances of capital and new technology, paradoxically, they are fortifying their borders against migrants. Since September 11, the general fear of the unknown has itself become more mobile, and has spawned its own >monsters<: terrorists in our midst and refugees on the move.

The horrors of terrorism do not compare to the minor burden of settling a few strangers. And yet, these two events are transposed onto the same paranoid level. The political discourse on migration has become the focal point of defensive reactions against globalisation, and the aggressive reassertion of cultural nationalism. Fear grows in the metaphors of flow and containment, and has now become most vivid in the way we describe mobility and belonging. It frames our suspicious glances at our neighbors, and extends into the state’s use of violence to exclude >outsiders<.

The failure of migration controls

Modern power cannot control global flows largely because it has not addressed the complex patterns of contemporary mobility. Traditional models saw migration as a finite, unidirectional movement. However, profound changes in the volume and trajectories of global mobility call for a new conceptual framework. Today, there are more people on the move than at any point in history,1 and contemporary migratory flows are multiple and turbulent. Between the two world wars migrant numbers doubled. By 1965 there were 75 million migrants; in 2002 there were 175 million, including 16 million refugees. Migrants have also diversified, shifting from the classical sociological image of an uprooted, lonely and poor man, to include men from all classes and status groups, and growing numbers of educated women. Complex forms of agency and spatial affiliation are emerging, with mass air transportation, new communications technologies and diasporic networks weaving complex new links across vast distances. Today’s migrants often choose their destination according to personal knowledge, networks and available transport,2 rather than purely economic concerns or geographic proximities.

Meanwhile, since the 1970s, migration governance has undergone significant shifts, with a new focus on controlling trans-national flows. By 2001 almost half the developed countries sought to restrict flows by dismantling migration recruiting agencies, limiting access to asylum claims, and introducing new detention and deportation practices, and the >safe country of origin< and >safe third country< principles. These measures have proven ineffective at best – and violent at worst. The lack of a global regulative authority continues to expose refugees to criminal people trafficking networks, and exaggerates fears on cross–border movements.

Governments do not admit that the history of migration controls is a catalogue of failures, and that migration is a driving force and product of globalization. And despite empirical evidence about the dynamic role played by migrants,3 the populist fear endures that migration threatens society, and the contemporary figure of the migrant is loaded with stigmatic associations of criminality, exploitation and desperation.

Art as a ‘dialogic concept’

The cultural dynamics of globalisation pose a challenge for scholars and artists: the urgent need for a more affirmative and critical response to issues of mobility and belonging. In response to the global refugee crisis, the >war on terror< and rising neo–nationalism, contemporary artists are employing strategies that oppose the border politics of exclusion, challenge the mainstream political discourse, offer alternative perspectives on cultural identity and initiate a new ethical quest for community. Working both locally and globally, they have seized upon the new communicative technologies to transform modes of production and interaction with their work, and to connect with like-minded agents in distant locations. In these trans–national creative networks, we witness flashes of creative resistance and hope.

In Australia, for instance, artists quickly showed their solidarity with the asylum seekers in the wake of the so–called Tampa crisis. In August 2001 the Norwegian container ship MV Tampa rescued 438 refugees from a sinking Indonesian fishing boat, and headed for the nearest port, in the Australian territory of Christmas Island. This conventional maritime rescue triggered an international crisis: the Australian, Norwegian and Indonesian governments refused to accept the refugees, and the ship was banned from Australian waters. A violent response unfolded, involving military interception, the re-drawing of Australia’s borders, the mandatory incarceration of refugees, a vilification campaign, an aggressive backlash against humanitarian refugee policies, and the so-called >Pacific Solution<4. Amidst hysteria over a supposed invasion, Australia’s immigration and asylum policies quickly switched from being some of the world’s most benign, to being global standard–bearers on violent exclusion and deterrence.

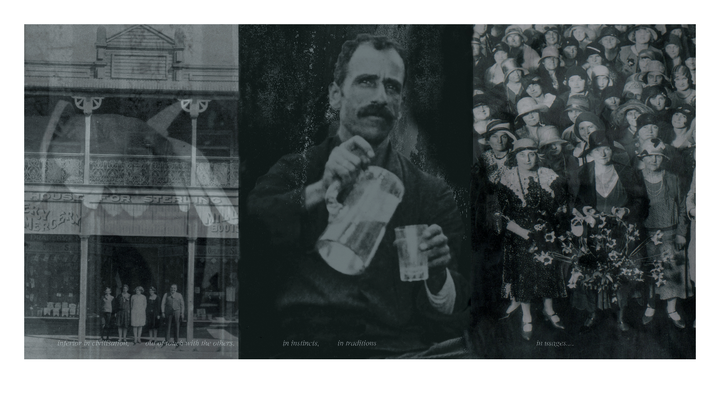

The exhibition (» Borderpanic «) was a powerful response to Australia’s >refugee crisis<. (» Legislation Affecting Aliens 1895 «), a collage by Vivienne Dadour, explored tense juxtapositions between place and meaning. The work combines archival images from the artist’s own family history, an early Christian building and an historical document declaring that Chinese and Syrian people should be excluded from Australia because they pose biological and cultural risks to the yet-unformed nation. The racist texts are juxtaposed against images of community and hospitality. At the centre is the inviting gaze and gesture of a man: an ancient, unequivocal invitation to share in food and drink, the arms open to embrace and receive. This generous gesture immediately offers >us<, the unknown viewer, the position of guest in his scene, despite the subject not knowing who is on the other side of the photograph – and it prefigures similar gestures made across the wire by refugees in Woomera detention centre: »Tell them we are human, we are not animals«.

September 11 and the >war on terror< have provided a stark reminder of the need to re–think the connections between art and politics. This profound challenge requires us to recognise that both political forces and cultural identities are caught in turbulent patterns of interconnection and displacement. As people move across boundaries, they bring different ideas and values.

Carlos Capelan’s sculpture (» My House is Your House «) (2005) is a stark reminder that hospitality is not unlimited hotel service. Capelan’s installations have repeatedly used the chair and a glass of water as a symbol of the minimum offering we can make to strangers. As part of his exhibition (» Only You «), at the National Gallery of Uruguay, he tied two stakes to the legs and back of an old fold-up chair. These prosthetic legs transform the chair so it resembles a tent frame, but the sculpture also carries the more sinister echo of a body thrust rigid by shock treatment. The invitation to share a house is a precarious gesture, for it splices the guest’s acceptance onto the host’s tensions.

Jacques Derrida has stressed that hospitality, unlike charity, as a >gift< made with no expectation of return,5 no expectation of gaining economic security or social status. »Let us say yes to who or what turns up, before any determination, before any anticipation, before any identification.« However, such an open-ended >gift< can never find a place within legal or political structures. As Derrida argues, the gift is also held together with strings. An unconditional welcome, a concept that he concedes is practically inaccessible, is also posed against its opposite, the imperative of sovereignty. The right to mobility must be positioned alongside the host’s right to authority over their own home. »No hospitality, in the classic sense, without sovereignty of oneself over one’s home, but since there is also no hospitality without finitude, sovereignty can only be exercised by filtering, choosing, and thus by excluding and doing violence.«

When two rights are posed as both legitimate and incommensurable, the task of negotiation becomes urgent. To betray hospitality in order to secure sovereignty is a moral loss. To denounce sovereignty for total hospitality is a political catastrophe. In this conundrum, decisions must made. As curators Maria Hlavajova and Gerardo Mosquera have argued,6 by virtue of its >dialogic concept<, art can play a vital role in participating in the conduct and content of these debates.

Is the barbarian already inside us?

Just over a hundred years ago Constantine Cavafy wrote the poem »Waiting for the Barbarians«7. Cavafy lived in the cosmopolitan quarters of Alexandria and was deeply aware of the general sense of unease in the city. He describes the foreboding that precedes an invasion, revealing how internal fears are spread by rumour, provoking panic. The city braces itself for the worst. However, despite the apocalyptic overtones, the poem contains an ironic twist:

Why are the streets and squares emptying so rapidly

everyone going home lost in thought?

Because night has fallen and the barbarians haven’t come.

And some of our men just in from the border say

there are no barbarians any longer.

Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?

They were, those people, a kind of solution.

The people had come together for defence, ready for a fight. But after all the waiting, nothing happens: neither conquest nor defeat. Cavafy intimates that something other than relief follows this realisation. The city had become dependent on the barbarians: they were indeed >a kind of solution<. With the barbarians outside, it is convenient to avoid asking the question: is the barbarian already inside us?

Many commentators declared that September 11 marked a >clash of civilizations<. However, when civilizations encounter difference they do not clash, but search out new avenues for dialogue and negotiation. Today, the ethical challenge for art lies in seeking more affirmative modes of engagement with issues of mobility, cultural difference and belonging. Art must face the question: in waiting for the barbarians, what do we sacrifice? What is the true cost of this fear and suspicion – and what are the alternative responses? Artists are approaching this project via local collaborations, through the trans–national alliances of diverse agents, and in the weaving of broader cross–cultural communities and networks. These flashes of creative resistance are by nature fragmentary and ephemeral. They do not offer simple or even unified solutions. But within this complex system of local resistance and global feedback, we can glimpse the potential for new discourses of hope.

1 Cf. Hania Zlotnik, International Migration 1965–96: An Overview, in: Population and Development Review 24(3). September 1998, pp. 429–468

2 Cf. Douglas S. Massey et al, Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford University Press 2005.

3 Cf. Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, Laurence Cooley and Howard Reed, Paying Their Way: The fiscal contribution of immigrants in the UK. Institute for Public Policy Research 2005, http://www.ippr.org.uk/publicationsandreports/publication.asp?id=280

4 The Pacific Solution was the name given to the Australian government policy (2001–2007) of transporting asylum seekers to detention camps on small island nations in the Pacific Ocean, rather than allowing them to land on the Australian mainland. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacific_Solution

5 Cf. Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantelle, Of Hospitality. Stanford University Press, 2000.

6 Cf. Cordially Invited, episode 3, Who if not we...? 7 episodes on (ex)changing Europe, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst. 31 October – 31 December 2004, http://www.bak-utrecht.nl/index.php

7 http://users.hol.gr/~barbanis/cavafy/barbarians.html

[1] Vgl. Hania Zlotnik, International Migration 1965–96: An Overview, in: Population and Development Review 24(3), September 1998, S. 429–468.

[2] Vgl. Douglas S. Massey et al., Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford 2005.

[3] Vgl. Dhananjayan Sriskandarajah, Laurence Cooley und Howard Reed, Paying Their Way: The fiscal contribution of immigrants in the UK. Institute for Public Policy Research 2005, www.ippr.org.uk/publicationsandreports/publication.asp?id=280.

[4] Als »pazifische Lösung« wurde die Politik der australischen Regierung (2001–2007) bezeichnet, Asylsuchende in Auffanglagern auf kleinen Inselstaaten im Pazifik bringen zu lassen, anstatt ihnen den Zugang zum australischen Festland zu erlauben.

[5] Die Ausstellung »Borderpanic« und ein begleitendes Symposion fanden 2002 in Sydney statt.

[6] Jacques Derrida, Von der Gastfreundschaft. Mit einer »Einladung« von Anne Dufourmantelle. Übertragen ins Deutsche von Markus Sedlaczek. Wien 2001, S. 60.

[7] Ebd., S. 45.

[8] Vgl. Cordially Invited, episode 3, Who if not we ...? 7 episodes on (ex)changing Europe, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst. 31. Oktober bis 31. Dezember 2004, www.bak-utrecht.nl/index.php.

[9] Vgl. http://members.fortunecity.com/ithaka/deutsch.html