Issue 4/2011 - Net section

Distraction from the Real?

The video-book »Learning from YouTube« by Alexandra Juhasz

As a cacophonic collection of serious and non-serious, disastrous and sometimes monstrous items – from the carefree adolescent interpretation of media icons and advertising clips to zoological observations of common domestic pets – YouTube, like most of the social-media platforms in the so-called Web 2.0, promises free availability without any preselection or taste censorship, by juxtaposing a wide variety of themes, formats and qualities, all on an equal footing. It seems as if the »prosumer« invoked by neoliberalism as the revolutionary subject of late capitalist media production and reception were behind the success of these platforms. The content produced in this way for users by users suggests equality and authenticity, and possibly also a new concept of plebeian education.

Alexandra Juhasz from Pitzer College in Claremont has, together with her students, developed a video-book that analyses and tests this promise. »Learning from YouTube« tries not only to analyse this social-media platform as a social phenomenon, a technology and a post-modern means of entertainment, but also to use and interrogate it as a method for scientific and educational communication. »YouTube is the subject, form, method, problem and solution of this video-book.« Logically enough, »Learning from YouTube« tries to condense/document the analytical processes and insights in so-called »texteos« (text + video = texteo) that lay claim to being an appropriate reflexive tool in the online era. Organised as 16 YouTours, theme-based trails, the videos of the project participants, found objects from YouTube and texts are combined to create media dialogues and disputes. All the videos produced by the team were, of course, posted on YouTube again; what is striking about the method is that »Learning from YouTube« makes extreme media proximity, or, better, mimicry, its subject and expressly intended this, too.

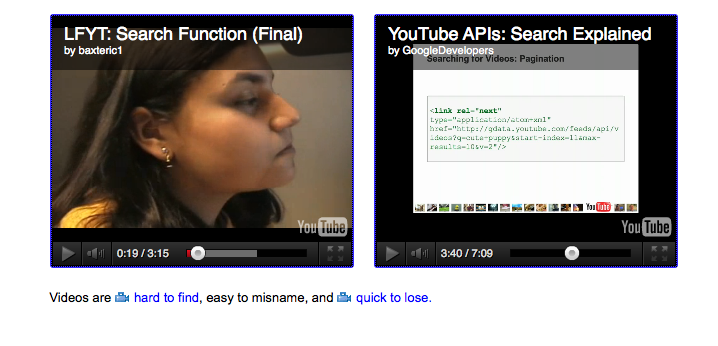

The analysis of the archival and presentational structure of YouTube shows that the sheer quantity of items produced each day, the approximate nature of the catalogue categories and the fact that those posting the videos are allowed to select their own descriptions make necessary a restrictive ranking system. The remaining resigned diagnosis is that this has therefore to be a very forgetful archive, in which items are as hard to find as they are quick to lose. But even more frightening than the archive’s structurally determined forgetfulness is the diktat of the masses, which pervades the platform on several levels at once. »Inappropriate« – by marking any video thus, people can report its content as being dubious in nature and put it up for examination by YouTube personnel. The degree of democratic consideration given to minority statements therefore becomes a corporate issue. YouTube is also oriented to the majority in the way it guides reception. Here, so-called niche items generally receive less attention and become invisible in a medium that organises its ranking structure according to »most watched«.

YouTube as a field of experiment for new video formats? Here, the conclusion is also a sad one. Videos produced professionally on commission from companies and private »Vblogs« dominate. So instead of blurring the boundaries between amateurs and pros as befitting the notion of the »prosumer« and negotiating new types of relationships between professional and amateur media productions, YouTube reaffirms these boundaries and relationships. An examination of the way minorities are tagged in videos opens up a dark space. Here, the cultural subconscious and the persistence of prejudices are revealed in all their monstrosity.

»Learning from YouTube« provides many interesting observations, analyses and criticisms of the »largest worldwide video community«. The structure of its open archive, which can be enlarged by every user, is cleverly and thoughtfully done; its navigation follows a logic of directed transparency. However, the »texteos« often seem too general and simple in their argumentation. The permanent superimposition of video and text dominates and marginalises the text, with the result that its output is mostly limited to the formulation of pragmatic statements. Revealingly, the selected catalogue of authors (to be found in the navigation list under »More« (!)) is fairly modest; no space is given to systematic theoretical debate as opposed to empirical, critical depiction. One is reconciled with these theoretical gaps in places where, for example, via a search for »Marx«, a reference to »form« appears with the comment: »We are always debating: Do you need radical forms to convey revolutionary messages?« and the referenced video by Stan Brakhage, »Mothlight« (1963), is shown – on YouTube, of course! The fact that the chaotic, pathetic, often ridiculous, ignorant and fragile structure of YouTube can lay false trails and has a readily accessible store of distractions from the real may be precisely one of the anticipated examples of what we can learn from YouTube.

The video book »Learning from YouTube« by Alexandra Juhasz has been online since February 2011. http://vectors.usc.edu/projects/learningfromyoutube/

Translated by Timothy Jones