Issue 3/2012 - Art of Angry

Trans*Europa*Lublin

Thoughts on queer-feminist art, activism and political critique in the Polish context

In 2012 the 3rd Transeuropa Festival was held simultaneously in 14 European cities.1 The free festival, run by the organisation European Alternatives and a transnational network of European activists, seeks to establish a shared political and cultural space to foster democracy, equality and culture outside the nation-state framework. In constructing a new society »from the bottom up« – an idea that however seems to be limited to an alternative Europe encompassing only European Union Member States2 – particular emphasis is placed on the role of the arts.3

»For a country like Poland that’s struggling with both democracy and religious fundamentalism, the problem of sexual difference can give art a margin for subversiveness and even revolutionary potential.«4

In May 2011 during a stay in Poznań, the city where I was born, a short article in the local edition of the Polish mainstream paper »Rzeczpospolita« about the Transeuropa Festival along with an image captioned as »shocking«, caught my attention. The piece in question, entitled »City of Love« by Jej Performatywność (Her Performativity – a pseudonym) was one of two artworks that hit headlines right across the country even before the festival began.5 It contains a depiction of homosexual love against the historic backdrop of the city and, according to the festival organisers, is intended to highlight Lublin’s » multi-faceted sexual geographies and histories«. The roughly 3 x 5 metre black and white graphic work – on a weatherproof banner with eyelets – ended up being shown only in the Homo Faber association’s premises, although originally it was planned to display it outside; because of its allegedly inflammatory content, the work was only accessible to visitors who had signed a written statement of consent. There was a discussion about tolerance and freedom in art immediately after the opening, and subsequently the work was rolled up once again.

A series of paintings by artist Katarzyna Hołda also caused a huge stir even before they were exhibited.6 The Madonnas painted by Hołda are stylised depictions of the Virgin Mary referencing pre-Christian symbolism, and drawing on the notion of the physicality of fertility goddesses, and are meant to be read in a feminist vein.

The response to these two works exemplifies a current trend towards constraining artistic freedoms in Poland, manifested in the scandals triggered by contemporary art that engages in a critique of society and indeed the way in which this art is presented in the media as the isolated position of self-satisfied artists. For example, the Indeks 73 initiative7 describes the way in which art continues to be highly marginalised and oppressed across the country and explains that censorship did not vanish in Poland after the fall of Communism. It is instead much truer to say that censorship simply assumed a different form and is mostly now manifested as pre-emptive (self-) censorship against a backdrop of economic, legal and bureaucratic pressure.

Although artistic freedom and freedom of expression are enshrined in the constitution, conservative politicians and the Catholic Church play such an important part in public life and in national politics that artistic practices – in particular if they reveal problem zones not addressed in the public realm – are often condemned due to these influences. This situation challenges artists to consider art as a tool for societal change and as a means of self-empowerment that identifies counter-hegemonic and emancipatory images and realities and that can imbue democracy with meaning in the contemporary context.

A groundbreaking work in this context was Karolina Breguła’s photo series »Niech nas zobaczą« (»Let Them See Us«) from 2003, the first countrywide social and artistic initiative against discrimination, which was shown in several Polish cities – in conjunction with the Campaign against Homophobia (CAH)8 – on specially leased billboards and in a few isolated cases in institutional spaces. The title of the work underscores the goal pursued by the 30 homosexual couples, holding hands and smiling at the camera, who agreed to be photographed in public places, namely to position themselves in the broader socio-political context. This shared public coming-out was apparently enough to provoke national resistance and opposition: this visual self-empowerment was accompanied by official bans, large-scale vandalism and a media hullaballoo, not to mention the subsequent decision by the firms who had leased the billboards to distance themselves from the project, whilst the All-Polish Youth movement even threatened attacks on those involved.

Tomek Kitliński, who initiated the first Transeuropa Festival in Lublin, was one of the people photographed in this context nine years ago, as was his partner Paweł Leszkowicz, curator of the thematic exhibition shown as part of the festival »Love is Love – Art as LGBTQ-activism, from Great Britain to Belarus«. Both address the expressions and visibility of sexuality in contemporary art and in »Love is Love« turned the spotlight on the sometimes shocking legal and cultural contexts in which sexual minorities in Europe live, by means of a wide-ranging selection of poster campaigns and artistic contributions. Here art and activism are interlinked and renegotiated through the expression of the »performing« of human rights, and are also embedded in the local context in Lublin: »Queer Bibliotherapy«, Kitliński’s installation, made up of 100 LGBTQ9 books, which encourages visitors to linger and browse, looks at literature and reading as a (historic) act of liberation, education and formation of identity, as well as an act of resistance in repressive times, and offers an accessible way to encounter homosexual and queer topics. However, Kitliński also adds that Lublin is not a tolerant city in this respect and that existing (national) discrimination continues to constitute an enormous hurdle in creating a society free of social exclusion.

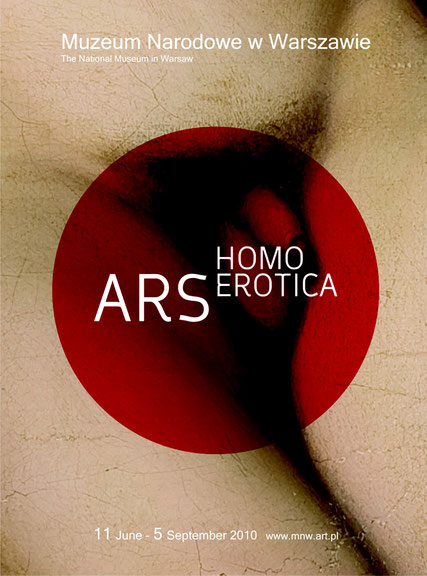

The fact that homosexual and queer culture is still alive and well despite structural and sometimes violent opposition, and refuses to be rendered invisible, was made apparent in the 2010 exhibition »Ars Homo Erotica« curated by Paweł Leszkowicz at the National Museum in Warsaw, under Piotr Piotrowski’s directorship: in a locus that seeks to reflect the historic grandeur of the entire nation, around 250 exhibits, combining pieces from the permanent collection and contemporary artworks, came together to form a »political and erotic, historical and contemporary exhibition«, addressing homoerotic forms of love. The heavyweight show managed inter alia to link the self-evident attitude to same-gender sexuality in everyday life and in art in Greek Antiquity with the anti-homosexual repression in the Communist era and indeed current repression by the Catholic Church. As a consequence, it opened up debates on the state of democracy and its continuing (national) political failure.

Like »Ars Homo Erotica«, the Transeuropa Festival 2011 in Lublin also addressed possibilities for emancipation in the sense of a »queering« by scrutinising socially ascribed and constructed social and sexual gender roles. In addition it took the notion of the homosexual as an outsider in the nation out of the religious and philosophical contexts in which this was depicted in the Warsaw exhibition and transposed this into Lublin’s urban space in order to add emphasis to the visibility and diversity of »other« cultures and minorities – from the past too – and their influence on the city’s now-vanished interculturality.

This is connected to the local working-through and examination of official historiography, an ongoing process since the early 1990s, a form of collective memory controlled in the post-war era by the Soviet Union, with history subordinated to ideological programmes. This process has for example led to knowledge about the Jewish district of the city vanishing almost entirely, just as the devastating impact of the Holocaust on Lublin’s numerous social, ethnic and religious minorities has slipped into oblivion. The close links between homophobia and anti-Semitism should be considered in the context of the public perception of the sole – allegedly the only possible – form of national-Catholic and heteronormative statehood, which is why – as Tomek Kitliński says – there is a need to act to combat » nationalist censorship, misogyny and homophobia, chauvinist-fundamentalist thinking and repressive religious discrimination«.

Art still has its work cut out in this respect, as is reflected in the fact that most of the programme points at the 2011 Transeuropa Festival that focused on topics marginalised in public discourse10 were on the whole ignored in the media – which simultaneously deprecated the word »Trans« in the festival title in connection with sexual minorities (»transgender«). As co-initiator Szymon Pietrasiewicz emphasises, in the future too art » will only be able to bring about a genuine change in how the problems it addresses are perceived by being constantly present in societal discourse«.

»The struggle over discourse as a political activity and as a pre-condition for engaging in left-wing politics «, is also the focus of the journal »Krytyka Polityczna«11 (En: Political Critique), which was founded in 2002 in Warsaw and seeks to contribute new critical impetus to public debate. Its website states that the process of »developing a societal project in the sphere of public space« must first be initiated in order to offer an alternative to the choice between» God or the market economy«. It goes on to explain that the roots of populism in Poland lie above all in the lack of channels – parties or media – that offer any scope for expression to those excluded from the transformation process or to advocates of a non-liberal economic discourse; and the journal seeks to ensure that a left-wing voice can acquire legal clout in order to bring about tangible changes in the balance of power.

Rafał Czekaj, club coordinator of »Krytyka Polityczna« in Lublin, ascribed an important role to the Transeuropa Festival in this context and described it as a »test of the openness of society and of the city «. In a discussion with Czekaj, he emphasised that the changes since the political upheavals in 1989 do not automatically lead to freedoms, as the interlinked political, cultural and economic transformations underway in society are based on longer-term processes, and underscored how urgent it is to address the question of actual participation in democratisation processes.

This year’s Transeuropa Festival, coordinated by Magdalena Łuczyn,also raised precisely this question of new forms of political mobilisation and democratic participation in the context of activism, art, migration policy and the economic crisis. Through public forums and study walks, protest picnics and flash mobs, it aimed to link up ad hoc forms of protest to move towards social practice and knowledge production that would function in the transnational arena. This is based on the realisation that current political networks – like the global Occupy movement too – did not spring out of a vacuum but that local protagonists in various fields have spent years building up such networks. Whether and how struggles with a regional thrust can become more effective with an awareness of global interconnections, or, to put it in slightly different terms how increasingly pronounced transnational networking activities can be transposed into different political contexts remains an urgent question, and very relevant too when it comes to devising the requisite instruments.12

There is little hope that the current Polish government, resolutely upholding its vision of national unity, will provide any support to minorities or help to make minorities more visible in the public realm. In order to bring about a shift in the current balance of resource allocation, dictated by market criteria, a different understanding of culture is needed – one that sees culture as a sphere with equal rights, which contributes to determining the shape a society assumes. To that end new spaces of representation initiated »from the bottom up« are of the essence, and it is equally crucial to devise a critique that is articulated in terms of ›we‹ – in the sense proposed by philosopher Marina Garcés – expressed not so much in a neoliberal notion of networking but in a sense of community and belonging:

» Nowadays, liberation has to do with our capacity to explore the networked link and fortify it: the links with a planet-world, reduced to an object of consumption, a surface of displacements and a depository of wastes; as well as the links with those ›Others‹ who, while always condemned to being other‹, have been evicted from the possibility to say “we‹. To combat impotence and embody critique then means to experience the ›we‹, and the ›world‹ that is amongst us. This is why the problem of critique is no longer a problem of conscience but of embodiment: it does not concern a conscience facing the world but rather a body that is in and with the world.«13

In addition to the people I have mentioned in the text, I would like to thank the following people involved with the festival for the content and experiences they shared with me in interviews and many personal conversations, as well as for their hospitality, which allowed me to gain a closer sense of the local context of the city in many different ways: thank you to Adrien Gros, Paweł Korbus, Radosław Łasisz, Magdalena Łuczyn, Jacek Rachwald, Piotr Salata, Józef Szopiński and Michał Wolny

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 In 2010 London, Paris, Bologna and Cluj-Napoca participated; in 2011 Berlin, Lublin, Prague, Bratislava, Sofia, Amsterdam, Edinburgh and Cardiff also took part; in 2012 Barcelona, Belgrade, Rome and Warsaw joined the festival, whilst Edinburgh and Cardiff did not participate.

2 As Belgrade is now participating, Serbia is the only non-EU country represented in this year’s festival, although it did acquire candidate-country status on 1st March 2012. That immediately gave rise to a conflictual relationship between the call to generate transnational counter-discourses in the public realms as part of social struggles and discourses on »Europeanisation« in connection with the European Union project, which produces new border constructions. A genuinely (euro-)centrism-critical, queer and post-colonial perspective on gender and identity formation seems extremely difficult under these conditions.

3 See http://transeuropafestival.eu/

4 Paweł Leszkowicz, Poland: The Shock of the Homoerotic, in: The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 3, 2003, p. 19.

5 There has been an air of scandal about the festival right from the outset, as co-founder and cultural activist Szymon Pietrasiewicz describes in a public in statement: first it proved difficult to find a venue to present »City of Love«, then the media became worked up about the festival’s problems in getting printing work done (a private printing firm had refused the contract). In addition, the fundamentalist Catholic radio station Radio Maryja described the content of the work as a contribution to a »festival of sodomites«. An official for the city council immediately had checks carried out to discover if taxpayers had to pay for the »orgy« depicted and threatened that this would have serious repercussions.

6 As the opening at the Labirynt gallery coincided with the anniversary of the attempted assassination in 1981 of the then Pope, one of the citizens of Lublin wrote to the mayor and claimed that the Madonnas constituted a criminal attack on the beatified John Paul II. The letter claimed this was an insult to all Catholics. The artist was subsequently questioned at Lublin’s police headquarters. The mayor’s spokesperson responded with a statement denying any responsibility of the city in connection with the work and referring citizens with complaints of any kind to the EU, which was funding the Madonnas as part of a festival.

7 www.indeks73.pl

8 www.kph.org.pl

9 »Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer«.

10 In 2011 the Festival in Lublin, as well as focussing on local minorities, also addressed contemporary politics, feminism, migration, university education and its commercialisation , philosophy, ecology and recycling.

11 www.krytykapolityczna.pl

12 The question of how many of the insights gleaned at this year’s Transeuropa Festival have been transposed into the local context will perhaps become clear at the next cultural event addressing the problem of discrimination in terms of the acceptance of the local LGBTQ community: the Week of Equality, from 28th November 2012 to 1st December 2012 in Lublin.

13 Marina Garcés, To Embody Critique; http://eipcp.net/transversal/0806/garces/en