Issue 4/2012 - Leben im Archiv

Art as Proposition

On the issue of the archive in the works of the Peruvian artist Teresa Burga

The theme of the archive figures in the work of the Peruvian artist Teresa Burga (b. 1935 in Iquitos) on two different levels. On the one hand, her work has only recently re-emerged from the archives to be exhibited again, thanks to the activities of two members of the Southern Conceptualisms Network 1, and on the other hand, the acts of collecting and classifying/organizing documents are of central importance to her practice. After 35 years of relative invisibility, Burga’s position attests to how the overstuffed Western-oriented (art historical) archives not only suffocate subaltern contemporary articulations, but completely exclude those of the past. This raises the question of whether, and how well, we can get along altogether without archives.

The Southern Conceptualisms Network is committed to preserving dissident art produced as a critical conscience under repressive regimes in colonial and post-colonial regions. 2 To what extent Burga’s works can also be counted among such critical political statements, for example against the military regime that came to power in Peru by putsch in 1968, is not immediately obvious.

Teresa Burga was one of the founders of the Peruvian group Arte Nuevo, which experimented in the mid-1960s in Lima with Pop Art and Op Art, with settings and geometric art, and found fault with traditional styles and institutions. A Fulbright Fellowship took her from 1968–1970 to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where Burga came into contact with semiotics and information theories. Her subsequent artistic work looked different as a result; she ceased to reference Pop Art and espoused instead a serial and conceptual aesthetic. Since that time, an exploration of language, communication and technology has played a central role in her works. After returning to Peru in 1971, despite initial doubts, she was able two years later to find a place for herself in the trend toward »non-objetualismo.«3 But she was no longer able to pick up the threads of her former network on the local art scene. Her works were exhibited only rarely.

Between 1975 and 2005 Burga worked as a customs employee. This paid work enabled her to continue to pursue her art without having to make concessions to the art market.4 The daily experience of the public administration and its bureaucracy would however leave its mark on her and her work. This is evident in a drawing from 1978 to which she added the official stamp of her workplace, the Secretariat of the Directorate General of Customs. She accompanied it with a drawing in ballpoint pen of an eraser on which is printed »Industria Peruana.« The date, the 20th of December, 1978, was stamped repeatedly all around. This gesture reflects the administration’s obsessive stamping of every piece of paper with dates and times to mark incoming and outgoing post, the beginning and end of a work process. The sheet, which has a somewhat mottled look due to the smudged stamp ink, was signed by Burga with expressive red ink. The time it took for her to complete this drawing during office hours was lost to her employer; Burga must hence have relished the fact that the word »industria« also connotes industriousness.

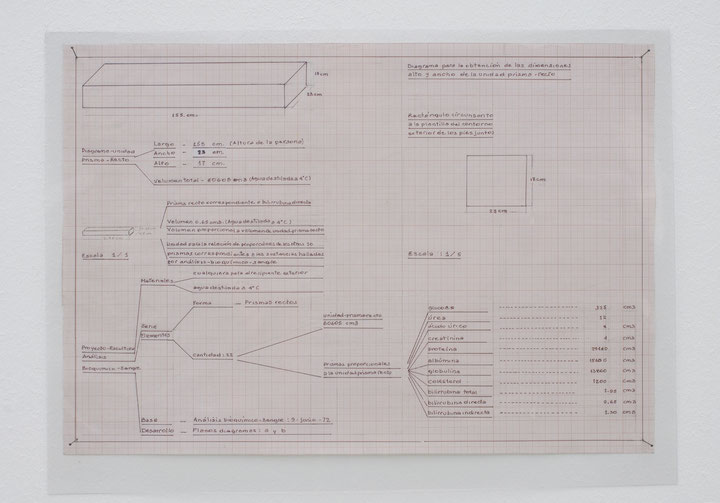

Her interest in the time and effort behind artistic work and the related temporal processes gave rise to logs in the form of marginal notes on drawings in which she accurately recorded the duration of production.5 Another form of log-keeping can be found in diagrams she drew on graph paper with the help of a ruler. In these, she structured her ideas and systematized her approach.

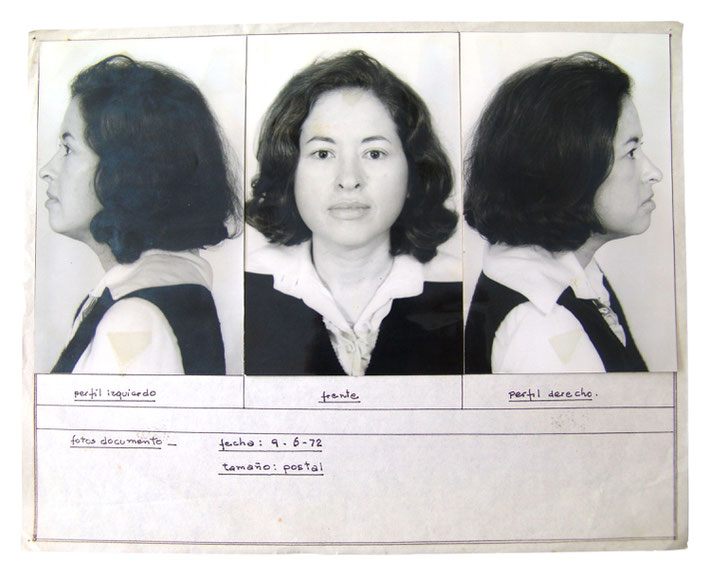

In 2012 the installation »Autorretrato. Estructura. Informe. 9.6.72« (Self-Portrait. Structure. Report. 9 June 1972) took up three walls at Galerie Barbara Thumm in Berlin.6 The title of this self-portrait reminds us today of the conventions for data file names, which indicate a file path or other organizational structure.

[FIG. 1 DETAIL OF FACE INDICATING DIMENSIONS]

Teresa Burga decided to divide her »Self-Portrait» into three »reports«: one on the face, one on the heart and one on the blood. On 9 June 9 1972, she had a cardiogram, an audio recording of her heartbeat, and a chemical analysis of her blood made for this purpose7 and had her face photographed from the front, left and right like in a mug shot.

[FIG. 2 THREE VIEWS OF TERESA BURGA]

The artwork consists half of these documents (documentos) demonstrating Burga’s commissioning of external experts: the piece of paper with the lab results as well as the receipts for the external services.8 The other half is made up of reduced, aesthetic productions, including a light-and-sound object that represents the recorded heartbeat, translating it into a pulsating red light.

[FIG. 3 VIEW OF INSTALLATION]

In historiography, the concept of the document is distinct from that of the monument:9 while monuments are made expressly for the purpose of commemoration, documents are testaments that are created accidentally, for example records from everyday life, law or business. Most likely without any conscious reference to this definition, Burga nonetheless incorporated documents as objects with a purpose other than the intended one into her artistic work, placing them in relationship with one another. She tends to opt for archival works when they serve to furnish a potential meaning for something that has previously been overlooked.10

Burga herself refers to her »art as proposal (or proposition),«11 alluding to its formal variability and structural openness. In 2006 she described in retrospect the process by which she gave up on »object-based representation« and began to see herself simply as a developer of generative structures.12

The diagrams and charts that figure in many of Burga’s works13 do not at first appear very variable. They seem to rely more on our faith in mathematical and scientific evidence. The limited number of basic elements and the pared-down structure simulate objectivity and clarity – an impression that quickly evaporates upon closer scrutiny. They therefore call for a comparative kind of looking, and the willingness to fill the diagrammatic strands with different kinds of content.

[FIG. 4 DIAGRAM OF REPORT ON BLOOD]

Burga thus also uses diagrams as a medium for encryption. She delights in perceptual complexities and detours in the production of meaning. By making it difficult for viewers to read her works and juxtaposing different signs that evoke divergent perceptions, she puts up resistance to any facile understanding of her art. Such communication complications were undesirable in Peru in 1972. Miguel Lopez describes the situation as »a movement inversely proportional to the socializing and populist communication strategies that the military government [under General Velasco] was deploying at the time.«14 Juan Acha likewise regarded the potential for enciphering content as an advantage of conceptual art in the face of the authoritarian governments in Latin America. He described its »cryptic character« as an opportunity for avoiding censorship and other forms of repression.15

Teresa Burga thus induces us to differentiate communication media from reality. Especially in the third report, on blood, the path to aesthetic translation of the chemical composition of her blood is paved with multiple diagrams. Step by step, she works out a complex code using colors and shapes to stand for the chemical values in order to finally arrive at a life-size diagram.

Each value, including those for cholesterol, glucose or proteins, is indicated with a small rectangle whose size depends on its proportion in the blood, all inscribed in a large rectangle that stands for the entire volume of Burga’s body.16 She has folded up the lower edge of the large sheet of paper so that it rests on the floor, forming together with the vertical plane a virtual volume. On the section resting on the floor, she has traced the outline of her bare feet. These visible signs on the floor signal Burga’s physical presence. Together with the sound and light signals of the heart and a series of silhouettes, which in the »Report on the Face« are also readable as an indexical sign, the measured and data-defined body takes on an unexpectedly tangible presence.

The fact that Teresa Burga herself chose to undergo these measurements makes all the difference. With her consent to this intervention in her physical integrity (in order to draw a blood sample, for example) and the publicizing of her private physical constitution, she sends a message about self-determination over her own, female body. She hence touches here – albeit in a covert way – on a central theme of the struggle for women’s rights in Peru.

In her self-portrait, Burga rejected the authorial shaping of material and form in favor of a collection of data about herself of various technical origins. In the project »Perfil de la Mujer Peruana« (Profile of the Peruvian Woman), which she executed in 1980/81 in cooperation with the sociologist Marie-France Cathelat, her attention shifted to documenting the realities of life around her. With the help of surveys and studies that Cathelat and Burga initiated for their joint project (they founded the association ISA – Investigaciones Sociales y Artisticas for this purpose), they generated data about a group of people that had until then been scarcely researched: middle-class Peruvian women aged 25 to 29 years. Several university institutes helped them to record anonymously the responses of 219 women. The aim was to find out more about their living situation and needs. The initiative thus took a stance against the paradoxical attitude of a patriarchal society that pretends to worship woman as the eternal feminine, while actually treating her as a »second-class citizen.«17

Twelve profiles were collected for each woman: physical, psychological, affective, social, educational, cultural, linguistic, religious, professional, economic, legal and political. The participating women were asked about their experiences with partnership and family, sexuality and birth control, and their opinions on divorce and domestic violence, as well as about opportunities for political and social participation.

[FIG. 5 COVER]

The results were presented in two exhibitions18 and a book. The cover of the publication »Perfil de la Mujer Peruana« shows a schematic representation of the female reproductive system. This was modeled on a depiction in a brochure on birth control.19 The new version however shows not only the uterus, ovaries and vagina, but also the clitoris. That the authors also ventured to depict the clitoris, as a sensitive zone in the battle for sexual self-determination, is quite remarkable in this extremely Catholic environment.20 Thus, already on the book’s cover a stance is taken on behalf of female sexual satisfaction, the importance of which is confirmed by the responses of the participants. From the responses given with regard to pregnancies and the number of children, one can also infer that some of the women had had abortions, in spite of the official ban.21

[FIG. 6 PERFIL ANTROPOMETRICO]

Another of Burga’s objects that was exhibited, and which was reconstructed in 2010, is the »Perfil Antropométrico.« Here, Burga sketched two views of a body shape, based on the recorded average body measurements of the women, on the sides of a glass cube in which she posed a naked mannequin. She thus compared »La Femme Moyenne Peruvienne«22 with the idealized mannequin. This is to be understood as an ironic commentary on standards of female beauty as shaped by the Western point of view. This critique of ideals of beauty, which goes hand in hand with the struggle for female self-determination, is typical of the emerging politics of »Second Wave Feminism« in Latin America.

»Perfil de la Mujer Peruana« straddles the boundary between sociological research and artistic practice. The ISA acted »in a process-oriented manner, without fixed intention or absolute aims.« Its efforts were geared toward »information and the possible processes that are connected with it.«23 From the subtle way in which the information was deployed, it was evident that the work was not intended as an occasion for political mobilization.24 However, the study certainly triggered awareness-raising processes in the participating women, as well as in the readers of the book and viewers of the exhibition. These processes are not documented and can scarcely be reconstructed after the fact.

What is the significance of such productions – which from the outset resist any fixing-down as object – for the desire for archiving? Emilio Tarazona sees in Burga’s persistent »contra-production,« which explores temporality and systematization, the nascent attempt to destabilize the power of hegemonic archives.25 Acting as a critical conscience, these works can moreover supply ammunition in ongoing clashes about freedom of speech and physical and informational self-determination.

Translated by Jenny Taylor

1 http://conceptual.inexistente.net. Miguel A. López realized with Emilio Tarazona the retrospective »Teresa Burga. Informes. Esquemas, Intervalos 17.9.10« and the eponymous catalogue. The exhibition was shown at the Instituto Cultural Peruano Norteamericano (17 September to 7 November 2010) and one year later at the Württembergischer Kunstverein (29 September 2011 to 1 January 2012), co-curated there by Dorota Biczel. Karin Jaschke reviewed the exhibition in springerin 4/2011.

2 »We use the provisional term of ›critical art‹ to name or define the realm of practices that we are interested in documenting and recuperating, all of which are linked with the experimental, dissent, activist and other emphases, but also other experiences linked to popular culture and the vernacular or indigenous aesthetics that propose other ways of understanding the contemporary, altering the temporal parameters of the history of Western Art as we know it.« López at the symposium »Speak, Memory,« Cairo; http://speakmemory.org/uploads/MiguelLopez.pdf.

3 The term was coined in 1973 by the critic Juan Acha as a criticism of the autonomous work of art and the capitalist art market, »as an emulation of the counter-cultural protests and performative artistic productions of the so-called Mexican ›groups‹ of the 1970s [...], and also as a reference to the indigenous aesthetics of popular art, crafts and design.« In his text »Back to No-Objetualismo: Returns of Peruvian Artistic Experimentalism (1960s/1970s),« Miguel López contrasts it as minority concept with the »Global Conceptualism« posited by Luis Camnitzer; http://www.manifestajournal.org/issues/fungus-contemporary/back-no-objetualismo-returns-peruvian-artistic-experimentalism-1960s, p. 24; cf. Juan Acha, Ensayos y Ponencias Latinoamericanistas. Caracas 1984, p. 221ff.

4 Cf. Miguel López, »Failed Conceptualisms: Aesthetic Wanderings and Political Drives in the Work of Teresa Burga,« in: ICPN (ed.), Teresa Burga - Informes. Esquemas, Intervalos 17.9.10. Lima 2010, note 41 on p. 194.

5 Based on the illustrations in the catalogue, it would seem that she began this practice around 1972 and continued at least until 1978.

6 Further information on the exhibition of the work of Teresa Burga & Anna Oppermann (2 June to 4 August 2012) can be found on http://www.bthumm.de.

7 She thus introduces the medical analysis of two culturally highly charged substances.

8 At the time Lopez/Tarazona did their research, part of the findings regarding the artist’s heart had been lost. To make a reconstruction of the work possible, Teresa Burga decided to repeat the examination of her heart, on 9 June 2006.

9 Johann Gustav Droysen, Grundriss der Historik. Leipzig 1882, p. 14

10 Emilio Tarazona has attested to Burga’s »complicity with the archive,« the archive understood here as »recovery-reinvention of the memory of the unnoticed.« Cf. Emilio Tarazona, »The Counter-Production of the Present. Some Ideas on the Work-Archive of Teresa Burga,« in: ICPN 2010, p. 175.

11 She spoke in a discussion on 2 June 2012 at Galerie B. Thumm of »art as proposal.«

12 Teresa Burga, »The Break Point,« in: ICPN 2010, p. 198.

13 A good overview is available on her website: http://www.teresaburga.com

14 Miguel López, »Failed« Conceptualisms, p. 186.

15 Juan Acha, »Teoría y Practica No-Objetualista en América Latina,« in: Acha, Ensayos y Ponencias Latinoamericanistas. Caracas 1984, p. 222.

16 The wooden cube emitting the red light (heart) signals is also based on the height of the artist.

17 Marie-France Cathelat, »Peruvian Women,« in: ICPN 2010, pp. 199/200.

18 In May 1981 she participated in the First Colloquium of Non-object Art and Urban Art in Medellín, Colombia, directed by Juan Acha. A larger presentation featuring diagrams, information panels and installations took place the same year at the Banco Continental in Lima, which had funded the project.

19 Interview with Teresa Burga in Berlin on 3 June 2012. Burga executed the construction sketch, and the cover design is the work of Jesus Ruiz Durand.

20 As a comparison, in Beatriz Preciado’s »Kontrasexuellem Manifest« (2003) the subversive potential of the clitoris is not even hinted at. Cf. Nanna Lüth, »Die Lindellmaschine,« in: Karen Wagels/Elvira Scheich (eds.), Körper, Raum, Transformation. Münster 2011, p. 87.

21 In 2008, Human Rights Watch found fault with the difficulties faced by Peruvian women needing to terminate a pregnancy for medical reasons. These reasons still include today an abortion that is performed to save the woman’s life or prevent serious health risks; cf. http://www.hrw.org.

22 Cf. Adolphe Quetelet, who in 1835 idealized the abstraction of the »average human« (L’Homme Moyen) as physically perfect type.

23 Teresa Burga, Untitled, in: ICPN 2010, p. 201.

24 Further information about the local reception at the time can be found in Miguel López, »Failed« Conceptualisms, pp. 189/190.

25 Emilio Tarazona, The Counter-Production of the Present, p. 174.