Issue 4/2012 - Leben im Archiv

The history of the panafrican culture festival and the difficulty of its archiving

Cédric Vincent

The history of the major cultural events that marked Africa’s official arrival on the world art scene has not yet been written. Three such events played a pivotal role in the development of the founding cultural and political movements in Africa from the 1960s to the present day: the first World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar in 1966, the First Pan-African Festival in Algiers in 1969 and FESTAC (the second World Festival of Black Arts) in Lagos in 1977.

Over and above the ebullient energy of these festivals, they also brought together and mediated between artists and decision-makers on the one hand and highly heterogeneous audiences on the other hand. These events also resonated like sound boxes, disseminating ideas previously confined to élites into the public domain. As a showcase for the organising states and participating artists they also functioned as antechambers of diplomacy, focusing attention through the prism of cultural creation on the issues at stake internationally on a number of levels: these included relations between young African nations; between North Africa with its predominantly Arab culture and Sub-Saharan Africa; between independent states and liberation movements in countries that were still colonised or subjected to apartheid regimes; between Africa and the Americas; between the former European colonising states and the former colonies; between international organisations and bilateral cooperation arrangements.

These festivals were therefore fully fledged protagonists as independent states in Africa came into being and took shape, whilst at the same time also bearing witness to the often violent transition as these states moved from the enthusiastic years during which they first gained independence to the crisis years (rise of dictatorships, outbreak of civil wars) that frequently followed in the wake of independence, and which led those countries to grow inward-looking and disillusioned.

When the trend to commemorate the anniversaries of independence took shape from 2000 to 2010, it was linked to explicit references to historic festivals: a second Pan-African Festival was held in July 2009 in Algiers; and in 2010 the Senegalese state reinstated the Festival mondial des arts nègres, holding the festival for the third time under the banner of the «African renaissance», a slogan coined by the former South African President Thabo Mbeki to define a new international image for the continent. The aim was clearly to once again deploy the symbolic capital of these foundational moments by rediscovering and reutilizing intellectual and artistic production linked to the ebullient years of anti-colonial struggle and independence. Initially the organisers certainly intended to tap into the euphoria of those days by reviving the festival format, yet this also entailed losing sight of the history and complexity of these events.

The paradox lies precisely in the fact that these events are so famous: they are cited as essential, foundational chronological landmarks, yet at the same time references to the festivals are very often full of stereotypes. The images and discourse they have produced are recycled, but always drawing on the same sources, namely the catalogues and above all the proceedings of the conferences held. One striking example of such stereotypes: depicting the 1966 Dakar festival as the festival of Négritude*, celebrating black African culture, and the 1969 Algiers event as an anti-Négritude retort to it. Even in cases where such stereotypes are overcome, the lack of documentation provided generally leads to a certain amnesia or at least to an aporia that reduces the festival to nothing more than the conference held there, in other words to its discursive and textual aspects, which are certainly less disturbing.

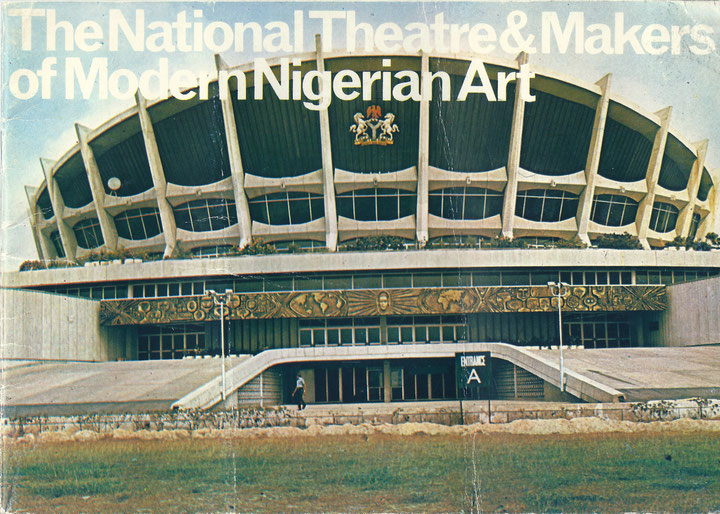

There are however archives which could offer a way out of this dilemma. The principal archives, preserved in the countries that hosted the festivals, as well as more fragmented collections of records, which are often not well-known, mainly contain administrative documents. These relate to formal organisational details. The fonds of the World Black Arts Festival deposited in Senegal’s National Archives was classified and indexed in 2001. However it cannot hold a candle to the document collection set up immediately after MFESTAC (Lagos). The Nigerian authorities decided to establish a cultural heritage institution with a remit to conserve the festival’s archives and to draw on this to create a museum of African art and civilisation. In 1979 this led to the establishment of the Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilisation (CBAAC), housed in the national theatre built specially for the festival. A true monument to FESTAC’s glory, it has however never really been exploited to the full by researchers, who are presumably intimidated by the sheer volume of documents held here.1

Most documents held to be archivable are linked to activities undertaken by the organising state and the partner organisations. This mode of collecting documentation highlights a national narrative, reflecting the original function of all archives. However, it overlooks the international impact of the Algiers Panafrican Festival, generated by the media-friendly presence of Black Panther Party members in exile in the Algerian capital. Furthermore, their presence tended to overshadow the contributions of other liberation movements. This approach to collecting documentation also overlooks FESTAC’s crucial role in the first wave of awareness-raising among the diaspora in the USA, the very diaspora that is now largely taking the lead in producing festival-related products and celebrations. In this sense the festivals are as much a part of independent Africa’s cultural and political history as of the history of the Cold War and the non-aligned movement, not to mention their contribution to the African-American diaspora’s élan.

Efforts to construct institutional archives, which form a kind of national monument, may well conflict with efforts to collect and archive records based on official requests for information, and stand in opposition to the multi-faceted «popular archive» produced both by the festival itself and outside the framework of the official programme. Discussions are shaped by these archives not only as sources of documentary information but also as sites of historical struggles relating to the writing, collection, archiving, destruction and interpretation of various records.

This means that it becomes important to intervene in existing archives, transforming them or indeed producing new archives, moving beyond archiving of administrative documents, which tend to be given pride of place and seen by many as the quintessence of knowledge, and instead extending the archival focus to encompass photos, literature, art, or performance. On this point, Diana Taylor has identified the tension that may exist between the «archive» and the «repertoire».2 She asserts that there is a dynamic relationship between these forms, for each sheds light on and nourishes the other. For Taylor, the term «archive» refers to cultural events that are preserved in a permanent fashion in media such as writing or photography, and that are consequently perceived as stable and eternal. In contrast, she uses the term «repertoire» with reference to practices such as dances, performances, political meetings, which follow a particular underlying «script» yet are nonetheless perceived as temporary and fragile, and are readily forgotten.

Taking this distinction as our point of departure would make it possible to convey the dimensions of the festival, for the discursive, visual, set design, and architectural productions generated by each festival, directly or indirectly, means that the festival makes its mark in a specific manner, with its own particular scale, extension, and modes of diffusion. The challenge that now faces us lies in recording, describing and filling in the contours of these imprints as fully as possible. There is nothing ephemeral about the impact of a festival, even if the festival itself lasts only a week or two. A multitude of traces remain, even long after a festival has ended. In addition to producing a significant quantity of printed documentation for participants and audiences (merchandising, stamps, commemorative catalogues, postcards …), this type of event also generates a flow of information (announcements, communications, rumours, minutes), its substance and quantity varying over time.

Take the example of the First Pan-African Festival in Algiers. Studying a festival of this kind immediately poses the question of sources. This is, firstly, because a specific section dedicated to documentation of the festival was not created in the national archives, in contrast with the Dakar and Lagos festivals. By their very nature, the various performances at the festival were fleeting; forty years on, our understanding of this collective experience remains in that ephemeral realm too. Of course, the various accounts of the festival in the Algerian, French or American press are still accessible. However, in seeking to really understand the festival, it can help to take other channels into account, even if these are more circuitous and less obvious.

For example, researchers can look into the world of jazz culture, for Algiers 1969 is a milestone in jazz history. The French record label BYG Actuel has produced several recordings of the musical performances. One of these, Clifford Thornton’s album «Ketchaoua» (1969), was developed specifically from his encounter with Archie Shepp’s quintet at the Algiers festival. In addition, this album also reveals Thornton’s pan-African awareness growing more solid, and demonstrates his support for the nationalist revolutionary politics of the era.

A number of important documents have been disseminated, fairly spontaneously, to mark the fortieth anniversary of the festival. Some photographers have digitised their photographs and put these images online.3 It is thanks to such initiatives that 35 photographs by Robert Wade are now available. It was also around the time of the festival’s fortieth anniversary that William Klein’s film was reissued as a DVD. Another – non-official – film also re-emerged during this period: a Direct Cinema short made by underground filmmaker Théo Robichet, showing an improvised concert by Shepp’s band in an Algiers street. It turns out that this film contains a plethora of additional information, above all because Klein’s team can be seen filming in the background.

Records like this allow researchers today to some extent to experience the festival as audiences did at the time. The documents produced in the course of the festival's two symposia have been published, though some of the festival's presentations, by the Organization for African Unity, are archived at the Royal Anthropological Institute in London.4 These documents reveal the exact language used in the symposium and are thus an invaluable resource to understand the debates on Négritude and how the symposia were structured.

One might object that some of these components are not (yet) archives in the strict sense of the term. Archiving involves a step of codification. In contrast, however, these sources draw our attention to the underlying question of the form an archive of this type of event should take, and turns the spotlight on historical and epistemological construction of archives established on the basis of the « gesture of putting to one side, collecting, transforming thus into «documents» certain objects that would otherwise be entirely dispersed and fragmented».5 These questions serve as a warning about the type of archive that is defined a priori : the archive as a depository of materials filed under broad general categories, material whose status is still indeterminate, situated somewhere between rubbish and relevance; material that has not been read or reviewed. It is clear that the archivist’s gaze depends on perception, on a discriminating gaze that makes it possible to extract an idea of an event from a mass of details and the importance accorded to them. In this context it is also important to consider the changes that shape and transform documentary materials, along with the routes and processes in which the major issues in commemorative, biographical, historical and academic terms are linked to a particular idea of the archive, for example the tendency to view the archive as a localised, fixed entity, not to mention the question of how to offer scope in an archive for stories that constitute an alternative to institutional narratives.

In addition, it is also necessary to consider the materiality of archives in all its different inflections — ranging from various types of graphic formalisation to the wide variety of formats in which documentation exists, the question of material manipulations and of a document’s emotional dimension — and address the ways in which this materiality offers scope to put to one side, even if only temporarily, the purely documentary dimension of archives in order to gain a clearer view of the artefact (as opposed to the document), manipulation (as opposed to reading), and the dimension of the senses (as opposed to that of rationality). This displacement of the gaze, emphasising the extra-textual dimension of archive documents, seeks to consider the archive empirically in terms of its practices, in other words, in terms of the operations, mechanisms and manoeuvres that enable various documents or materials to serve as evidence at a particular point in time, by mobilising these to bear witness to the past, to a specific history.

The festivals in question form part of several intersecting and contradictory histories.

Instead of conceptualising the archive as a place where time is arrested, archives may become a project or an aspiration, a site for the production of anticipated memories by intentionally engaging in imaginative and creative work to form new collective memories, which are distinct from official memories. An archive of this kind might be viewed as an active aspiration, a tool for reworking desires and memories.The metaphor of the archive enables us to rethink the past through its very materiality and to act upon it creatively in order to imagine new futures.

* Négritude is a literary and ideological movement, developed by francophone black intellectuals, writers, and politicians in France in the 1930s. The Négritude writers found solidarity in a common black identity as a rejection of perceived French colonial racism.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

1 American anthropologist Andrew Apter witnessed the transformation of this archive into a national monument, which therefore also introduced very precise rules on consulting the archive. Cf. Andrew Apter, The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture in Nigeria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

2 Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, Durham: Duke UP, 2003.

3 Documents: Doctrines, Fine Arts, Ethnography, Variety Archie Shepp - Live At the Pan-African Festival Cf. http://surrealdocuments.blogspot.com.

Robert Wade, Pan-African Cultural Festival Algiers 1969.

Cf. http://rw.photoshelter.com/gallery/Pan-African-Cultural-Festival-Algiers-1969/G00009FIzUoMuNQ.

The first link is to a blog, containing links and other resources related to the festival. The second links to the homepage of Robert Wade, a professional photographer who attended the festival. Information gleaned from personal websites needs to be handled with caution, but these examples provide access to legitimate sources that would otherwise be impossible to consult.

4 Royal Anthropological Institute, Pan-African Cultural Festival, First (MS 412). http://www.therai.org.uk/archives-and-manuscripts/manuscript-contents/0412-pan-african-cultural-festival-first-ms-412/. The papers come from William Fagg.

5 Michel de Certeau, L’écriture de l’histoire. Paris [1975] 2002, S. 100.