Issue 1/2014 - Net section

Working on Paper, Working with Paper

The mechanical logic of Ignacio Uriarte's artistic practice

Reproducing and varying, folding and stacking, arranging, allocating and rearranging, testing and rejecting, leaving things to chance and reproducing again: everyday working life in an office barely differs from that in a artist's studio – in both cases, material is brought into shape. The Spanish-German artist Ignacio Uriarte is familiar with both situations. As an economics graduate, he spent several years in international concerns and knows the corporate mechanisms that determine the daily routine between stacked copies, ballpoint pens, Excel lists and the curse of time. As an artist, too, he uses materials, media and formats such as the 297 x 210 millimetre DIN A4 sheet, whose dimensions may not be generally known, but which is employed ubiquitously. He works with printing cartridges that always leave behind their traces somewhere, with the blue, red, green and black of the BIC Cristal or the precise grids of calculation tables and graph paper.

“After I left my last office job and decided to take up art as my main profession, I realised that the newly-won freedom entails a great responsibility,” Uriarte writes in his online portfolio, which is arranged in numbered folders in bureaucratic manner: “Under no circumstances did I want to misuse art to bring about a personal liberation that would make me conform to a reactionary and marginal cliché artist. Quite the contrary: I decided not to leave my own petit bourgeois reality at all so I could engage with it from the inside with the necessary specialist knowledge.”1 Ignacio Uriarte produces his art with analogue means, but in his method he follows a mechanical logic that is defined by 0 and 1 and that is coming more than ever to shape not only everyday 21st-century office life but also daily studio routine. The artist experiments with the tools that he knows from his past professional life by confronting the sequences of actions that are linked with these tools. According to the artist, these are “laughably trivial” gestures and routines such as folding a letter before placing it in an envelope or scribbling on paper during a telephone call. The result that Uriarte achieves by repeating one and the same movement pattern gives rise to art works that draw on the formal language of minimal and concept art and bring viewers face to face with generative methods of art production in a digital era. The endless loop – both in artistic and in economic-business contexts – becomes a principle and a theme.

The video Infinity (2010) typifies Uriarte's artistic strategies. On the screen, we see a lemniscate drawn on paper: a loop-like curve that, however, completely lacks the perfection that it normally possesses as a symbol of infinity. The lying figure-of-eight is neither symmetrical nor closed. It has a beginning and an end, which results from the movement of the drawing utensil when the artist puts the shape on paper. Nonetheless – or precisely for this reason – the video corresponds with the concept of infinity, for Uriarte, setting out from the first handwritten lemniscate, has traced drawing after drawing and strung together and animated the separate sheets until the opening in the video – the mistake – moves along the curve, encapsulating infinity using the means of video technology. “The absence of a goal and a reason guarantees the absence of instrumental thought,”2 writes Diedrich Diederichsen about the loop as a contemporary principle. The constant transformation of the original form and the mobile element of the flawed lemniscate in Infinity are what allow the artist to free his activity from every purposive rationality.

A number of other works show how Uriarte explores socio-political complexes such as work, the production of art, the availability of resources and the elapsing of lifetimes and working time in a manner that is not just systematic, but also based on the use of means that are intrinsic equally to the systems “office” and “art”. In the 60-second video Accumulative Clock (2006), we see all Arabic digits from 0 to 9, which the artist scribbles onto graph paper at ten-second intervals using a pencil. During the space of a minute, so many digits are superimposed on one another that an artistic form arises that again reminds one of the symbol for infinity. For the installation 60 seconds (2005), Uriarte arranged digital watches to form a circle. Each watch is one second ahead of the one before it, making the absurdity of the mostly eight-hour working day countable with the speed of one circle per minute. This element becomes even more obvious when the automatic signal tone of the watches begins to sound every full hour, continuing on from one watch to the other second after second and creating a spatial-aural experience.

In the video Fluorescent Animation (2009), in which three horizontal coloured strips continually rearrange themselves in a downwards movement, the artist focuses on the potential of the resources that often lie idle in the office. The possible combinations of the standard colours of the Stabilo Boss highlighter undergo a rigorous exploration here and are linked almost too literally with the colour field painting methods of artists such as Mark Rothko. The eight colours available to highlight content – yellow, orange, three shades of red, green, petrol and blue – are also at the centre of Fluorescent Monochromes (2008). The order of the eight monochrome pictures drawn line for line with a ruler matches the order of the pens in their original packaging. Nothing is left to chance.

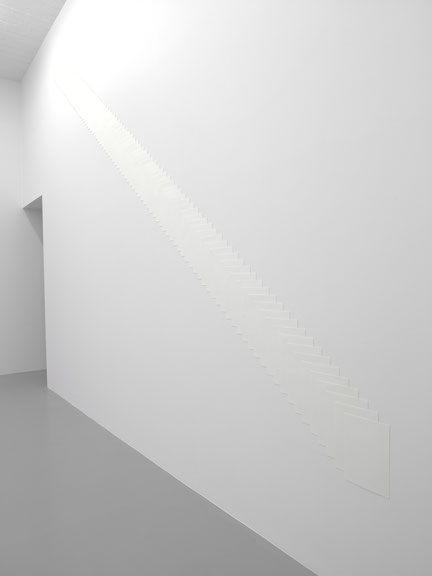

The omnipresence of the digital in all settings of our lives is evident in the installation Copied Document (2010). People who open several documents in programs such as Word, Excel of Photoshop to work with different content at the same time know the windows that are superimposed on one other down on the right so that one can keep track. With a series of DIN A4 sheets on the wall that also continue down towards the lower right-hand corner, the artist not only brings a digital phenomenon back to the physical world from which it comes, but also visualises the never-ending loops of daily multi-tasking and compulsory production. “Noticing that one has gone round in a circle,” says Diedrich Diederichsen about the phenomenon of the loop in present-day artistic production, “normally indicates that one has lost one's way. But many people also find that quite pleasant.”3 In the case of Ignacio Uriarte, there is no more that needs to be said.

Translated by Timothy Jones

1 Ignacio Uriarte; www.ignaciouriarte.com

2 Diedrich Diederichsen, Eigenblutdoping. Selbstverwertung, Künstlerromantik, Partizipation, Cologne 2008, p. 19.

3 ibid, p. 29.