Renate: I realized that many art practices in my field are not engaged with a transformation, a crisis or a catastrophe, but in fact with the "time after", the time "after the transformation", with long-lasting and persisting situations (the persistence of medical or bodily conditions, of daily routines, of living in a Palestinian refugee camp for decades, of living in the time after a war, the endurance of homophobia...). I wondered if the temporality of "the chronic", that you, Elizabeth, explicated in your lecture at our common event in Venice in 2011 , might be an adequate way not only to describe some less spectacular, often overlooked, political conditions around us, but also to intervene into normative temporal time patterns of progress.

The chronic is taken from the realm of medicine or sickness, it is a condition or situation, which is exactly not acute. It might not be dramatic, or threaten our lives but it is engraved in the course of our daily routines, it might be quite present with pain or other types of suffering. It even might be or become constitutive of our bodies. Thus, it might not change or endanger live but rather constitute live. In this way the chronic could be seen as a state of excess, that – in Judith Butler's sense – we "are given over" to the other and to conditions outside ourselves, which are "undoing ourselves", that we are, in fact, "ec/static" or "queer". On the other hand, the fact that we are not sure about the past and the future of the chronic (where it comes from and where it might lead us), might open it up especially for neoliberal types of self-government: its indeterminacy might not be liberating, but produce an agonizing and haunting type of (sexual) labor , a way to question oneself continuously: Are we guilty of bad self-care in the past? How might we take effect on a future that is insecure?

Elizabeth, you mentioned in your lecture that the chronic seems to be a "promising temporality" for you...?

Elizabeth: I think that in the ways you describe, the chronic absolutely has the capacity to intervene in the rhetoric of crisis, to describe conditions of being ground down, worn out, or merely making do rather than the states of emergency that are connected to calls for political action (and I should say that I owe a lot to Lauren Berlant’s conception of slow death here. What I love about the way she formulates the concept is her framing of it as something that can intervene on the „novelistic“ question of what counts as agency – the idea that we are the heroes of our own lives and they should constitute a series of triumphs or setbacks). The chronic is associated, too, with the habitual, with incremental or accretive movements that might not even go forward (Kathryn Bond Stockton’s account of „sideways growth“ is also useful here, though I am not sure that everything that accretes should be counted as „growth“ in the progressive sense.) Yet as you point out, it feels impossible to live in the time of the chronic without casting backward to faulty behavior or forward to the promise that if we do well, we might live in the time of, at least, remission. So I think we have to dwell in the chronic in which we are, in many ways, simply forced to live. That’s why in the piece you cite, I turn to a subcultural use of „the chronic,“ a slang term for very potent marijuana. Whatever else can be said of pot, it enlarges the present, changes relations of scale, and makes pleasures out of the mundane (who, being stoned, has not gotten lost in contemplating, say, a paisley pattern or the interesting movement of a sponge doing dishes?). That version of the chronic suggests that, absent a secure origin or future, there may be promise in dilating the present – perhaps in occupying it hyperbolically, in the way that one has to do in moments that are technically not under our control, such as waiting for something, or being present to someone moving more slowly than we are.

Mathias: In my work on aesthetic practices that engage with unfinished histories of injustice, I find that the figure of the chronic raises important questions on the political effects of temporal diagnostics: What are the consequences of shifting the conceptual framework from crisis to the chronic, from the epidemic to the endemic, from progression to lateral gestures of “ongoingness”? From an analytical point of view, thinking through the chronic might be a way to challenge the dominant economies of political attention that privilege happenings that conform to registers of the eventual – with the intensities of ruptures and clashes and immediate sense of change. Tuning into the temporal rhythms of the chronic might in short provide a possibility to hear other stories or other sides of stories that risk being overlooked, forgotten or displaced within critical strategies oriented towards dramaturgies of sudden transformation or movement. Like Elizabeth, I have been drawn to versions of the chronic that aim to challenge chrono-normative frameworks of political agency, historical progression, and economic growth. And Lauren Berlant’s work has also been central to my interest in giving texture to living and feeling politically in relation to the “crisis ordinariness“ of endemic and interlocking problems such as HIV/AIDS, population racism, structural sexism and homo-, bi-, transphobia, global capitalist exploitation, material dispossession (and I could go on, as no „etc.“ could stand in for the proliferating scenes of injustice towering up around us).

While the chronic can enable us to mine the presence of pasts that are not passé, dilating the present in Beth’s formulation, I’m reluctant to posit the chronic as a queer figure per se. The chronic can surely be used in queer ways to open up alternative ways to inhabit the present, and close-circuit binaries of life/death, activity/passivity, capacity/debility, and transgression/status quo. But as Eric Cazdyn points out in his analyses of how forms of “chronic time“ operate in different cultural-political realms in the book The Already Dead (2012), the chronic can also be taken up and used in ways that risk to naturalize and eternalize brutal logics of the present. From current chronic modes in medicine, that shifts focus on curing to forms of management and stabilization, to the chronic crisis in the economic systems of capitalism, that keeps producing endless series of preemptive rescue missions, Cazdyn’s criticism of „the new chronic“ stands as an important reminder of the ways in which the chronic might colonize ideas of alternative futures. I’m thus quite interested in Cazdyn’s argument that this new chronic order suggests the importance of working on removing the distinction between life and death (which enables us to queer bio- and necropolitical structures and ideologies), while simultaneously working to retain a relative autonomy between life and death, to keep an opening for imagining radical change.

Renate: Do you think that these modes of the chronic, that you describe with reference to Cazdyn, could be addressed as "chronic crises" or as "crisis ordinariness"? It seems to me that rather the repetition of crisis, that attracts and chronically binds our attention, colonizes ideas of a different future than the exposing of chronically bad conditions of life. In the introduction to her last book "Economies of Abandonment", Elizabeth Povinelli refers to the novel "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" by Ursula Le Guin. The novel speaks about a city, Omelas, the "city of happiness", where a child is trapped in a broom closet. The happiness and well-being of all inhabitants of Omelas depend from the suffering of this one child. The inhabitants react in different ways to this "chronic" connection: Some remain with their very vague knowledge about this condition, some visit the child from time to time, some think that the child is already too damaged to even think about uncaging and freeing it. Only few inhabitants leave Omelas, but there is no knowledge or imagination about the place they go. Povinelli’s point is, that chronic abjection, despair, impoverishment, and boredom are a much quieter form of misery, not very spectacular and not useful to produce an ethical impulse towards change. She differentiates between, as she calls it, "quasi-events" and events: "If events are things that we can say happened such that they have a certain objective being, then quasi-events never quite achieve the status of having occurred or taken place. They neither happen nor not happen. ... Crises and catastrophes are kinds of events that seem to demand, as if authored from outside human agency, an ethical response. Not surprisingly then, these kinds of events become what inform the social science of suffering and thriving,..." (13f) This means that the chronic might be useful as a means of describing events that are not even events and as well as a politicization of quasi-events - such as the endurance of suffering from Aids "after the crisis" (which usually only addresses a specific time of resistance in the late 80ties and early 90ties New York).

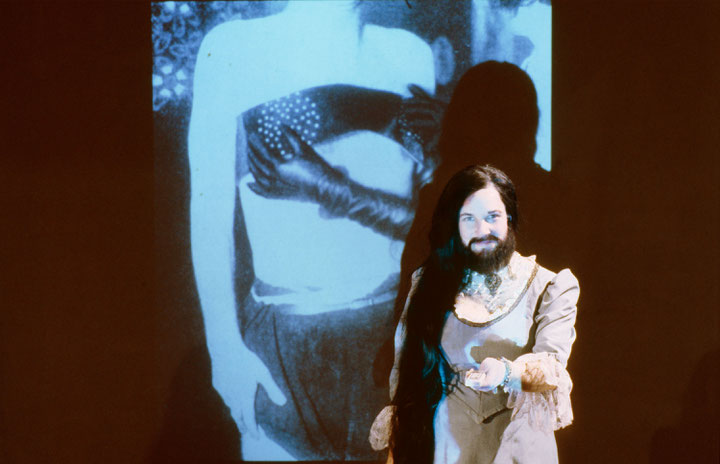

In our film installations Pauline Boudry and I usually work with loops, this means, short films, that are edited in a way that they have no proper beginning and ending but that they start again in a subtle way that you might not even realize. I often had the impression that these loops–without any direct intention–address in an uncanny way artistic and activist political maintenance work. Sometimes it seems as if those figures in the film come back day and night and unrestingly perform their labor of working on change. In our film "N.O. Body" (2008) for instance, a drag performer works himself through the history of othering or pathologizing images of cross-dressers, lesbians, fetishists or bearded ladies. In our last film "To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of Their Desperation" (2013) a bunch of musicians meet to perform a strange score, and after a few minutes they repeat their task. If I come back to the same exhibit after a few weeks, they are still, unfailingly, doing it... Mathias, in your book you speak about artistic practices, that refer to the "durational 'now'" in political protest, works that sidestep "a progressive concept of presentism that only values what is "useful" in the here and now", about art works that take their starting points at "unmemorable "nonevents", shaped around the habitual rehearsal of political agency. How do you see, despite your skepticism, the potential of artistic practices to make use of the chronic as a method or a perspective?

M: When I am reluctant toward claiming the chronic as an intrinsically queer figure, it is because I want to avoid fetishizing a temporal form that despite its usefulness to queer criticism of chrono-normativities, also can be used in conservative and conservating ways. It might therefore be important to try to distinguish between different ways of working with the figure of the chronic, not to differentiate between „good“ from „bad“ „chronicities“, but rather to get a better sense of the different forms of work this figure perform in our cultural debates. Here it might be helpful, as you imply Renate, to distinguish between ways to use chronic as a method, and the use of the „chronic“ as a diagnostic for particular states of existence.

In my project Touching History, I engage with feminist and queer artistic visual art and performance that strategically deploy temporal forms and gestures––including figures of anachronism, simultaneity, and the more chronic-oriented figures of duration and repetition––to interrupt, confuse, or disturb historical narratives of progress in relation to unfinished histories of injustice. The project is in many ways fueled by a kind of chronopolitical separation anxiety, a stubborn refusal to automatically accept the mechanisms that distributes status and relevance––pastness and presentness––in historical and political engagements with ongoing structural problems that often stand at risk of being prematurely historicized, and thus disarticulated, from the present.

I have been drawn to work that deploys chronic strategies, such as looping or other forms of endless repetitions, like the ones deployed by Pauline Boudry and Renate’s seamless editing of the lecture performance in N.O. Body, or the use of carousel slide projectors in Sharon Hayes’ work In the Near Future (2005-8). In this work that invokes different unfinished histories of political activism and demonstrations, the carousel slide projectors makes the photographs of the lonely activist standing on the street appear again and again and again in an endless cycle––a use of repetition or insistence (to invoke Beth’s reading of Gertrude Stein’s chronicity) that among other things highlight the temporal labor of repetition so central to activist work, where political claims must be raised over and over again in ways that can feel quite stuplime, as Sianne Ngai has described the sense of being overwhelmingly excited and bored at the same time.

In these brief examples of artistic engagements with strategies or looping and repetition, the chronic seems to be used to examine, give attention to, or expose what you Renate described earlier as „chronically bad situations of life.“ Chronic artistic „methods“ can in short be productively used to disrupt or intervene in dominant economies of attention that prioritize political scenarios that trade on the eventual and spectacular. The chronic can in other words be used artistically to describe or intervene into the already chronic scenes of the „crisis ordinariness“ (Berlant) of the „quasi-eventual“ (Povinelli) unlivable lives. Here artistic work can use chronic methods to work against chronic states of dispossession. Chronic methods can in short inspire us to refuse our growing ability to bear the unbearable––as in states of „crisis ordinariness“––as they can make us see that the challenge might rather be to make the „bearable unbearable,“ as Cazdyn puts it. Some artists can thus be seen to use chronic methods to alter those chronic states that we do want to change. After all, progress in itself isn’t always bad, not if it refers to working to terminate structural endemics such as HIV/AIDS. Artistic engagements with what I call „durational nows“ in relation to repetitive violent scenes of inequality that unfold not only „now“ but „now“ and „now“ and „now“ unendingly, often gesture toward ending this durational „slow death“ (Berlant). When chronic methods are used in these artistic contexts, they seem to balance between a desire for making scenes of inequality history and an anxiety for premature historicization of these unfinished problems. Using loops and repetitions can in this sense force us to address important questions such as: when is history history? And who decides when a problem has been solved?

These ways of using the chronic as a method to try describe and/or alter chronically bad political states surely differ from the uses of the chronic that Beth talks about in relation to drug culture. Here the chronic seems to work as a strategy that slows down or seemingly stops flows of activity––a „dilating“ of the present whose effects can be manifold but that might include a distortion of capitalist machineries of efficacy (or not). I’m in short interested in the different work that uses of the chronic can perform, and here it seems necessary to following the figure around in different contexts.

Elizabeth: I think Mathias has laid out some crucial distinctions here: between the chronic as diagnostic and as method, and between the chronic as manifested by repetition and looping on the one hand, and by dilating on the other. I’ll turn to the latter one only because he’s done such a splendid job with the former! But there is a version of the chronic that is not about repetition, that does not seem to be about movement either backward or forward; rather, it’s about not having any kind of „break“ within which to begin again, detour something, or mark openings and closures. The chronic can also name the state of being what we call in the United States a „frog in boiling water,“ where the intensity of something increases so gradually that you do not notice, whereas if it began at that level you would call it a trauma or a crisis. There is something horrifying about the adage that one can get used to anything, and I wonder what kind of artistic practice can foreground that process, whether to disrupt it or simply to call attention to the way we live now.

An article we published in GLQ recently, in Jennifer Doyle’s special issue, „The Athletic Issue,“ gets at something of what I am after here. In „‚The Horse in My Flesh’: Transpecies Performance and Affective Athleticism,“ (GLQ 19.4, 2013: 487-514), Leon J. Hilton takes up Marion Leval-Jeante and Benôit Magnin’s piece que le cheval vive en moi (May the Horse Live in Me). This performance piece involved Leval-Jeante receiving transfusions of horse plasma, having first received a series of injections of horse immunoglobulin to prepare her body and to keep it from rejecting the proteins in the horse blood. Hilton’s is a brilliant analysis of this performance, and I don’t want to steal his thunder–everyone should read this piece! But what strikes me about que le cheval and this genre of art—I’d claims it as endurance art, extending that concept outward to the arena of sport as Hilton asks us to do in this piece and Doyle asks us to do in her special issue—is that it recaptures and hyperbolizes this process of getting used to things, of literally incorporating what is unbearable to our well-being.

So rather than turning every time to avant-garde art, to get at this version of the chronic I might turn toward a very American spectacle: „extreme“ feats of endurance such as weight-lifting, tree-sitting, or even pie-eating. Most of these require long, slow regimes of preparation, processes of strengthening or stretching or modifying the body and its responses, and in this sense they seem just disciplinary in a not very interesting way. But when they spectacularize as a burst of intensity or a moment of sensory overload what has actually taken months or years to produce, they get at something of the chronic state I am trying to describe, in which we are shown as „crisis“ or „event“ something we have actually lived with for a very long time, have even naturalized as just life itself.

Like Mathias, I am loath to claim the chronic in and of itself as queer, but I do want to mark what seems queer about the version of chronic method that I see going on in endurance art. One aspect is temporal; when an endurance piece incorporates the slowness of preparation or performance into the event itself, it brings us back to labor, to the work necessary to make a body or a commodity, and in that sense reminds us that where we are now has a history; whereas when an endurance piece showcases a burst of intensity it can illuminate just exactly how painful are the ordinary conditions of our existence. The other aspect is corporeal: endurance art is not just about the prowess of bodies, but about the ways bodies sometimes endure even when we don’t want them to, when it would be easier to just jettison them. This is the aspect of „insistence“ that makes the chronic, I’d argue, somewhat different than the repetitive.