Issue 2/2015 - 20 Jahre – Zukunft

Bifurcation and Autonomy in Experimental Cultural Production

[A Remembrance for Springerin’s 20th Anniversary]

At this point in the twenty-first century, few observers of experimental arts would object to the notion that there are currently two distinct and functionally autonomous models. The elder of the two is characterized by expertise in a given specialization that manifests as mastery over a fixed set of materials and advanced technical competence. The task for makers is to radically push or reconfigure aesthetic conventions within the specialization without breaching the specialization itself. As the older of the competing models, its bonds with the institutions of distribution and funding lines are much stronger, so much so that it dominates resources. The junior model is characterized by a nomadic tendency to wander through various specializations to acquire and repurpose materials and processes in order to reconfigure culture into alternative forms of perceiving, thinking, and living. These two models could exist in relative peace (with perhaps a skirmish here and there over common resources) were it not for the insistence of the younger on systemic reorganization of the status quo. In other words, while nomadism can be generally tolerated, one interrelation that cannot be accepted by the dominant model is the one between culture and politics. These two must be maintained as separate at all costs, for failure to do so would reveal the true status of those who serve only to challenge convention as high-end manufacturers (although often well paid) for the luxury/investment market as opposed to heroes of free expression.

The Call

The idea of what needed to be done, if there was to be a sector of cultural experimentalists capable of contributing to resistance against the powers of domination emanating from capitalist political economy, came well before the practice. By the mid-twentieth century, a few key ideas had surfaced. First, the avant-garde as it had been—as a specialization within the specializations of art, literature, theater, and music—had become counterproductive in regard to systemic change. As Roland Barthes famously quipped in Mythologies, “What the avant-garde does not tolerate about the bourgeoisie is its language, not its status.” It’s happy to leave the system intact if it can push the possibilities of expression within the system. The companion “revolutionary” form that did object to the system was particularly embraced by those enveloped in various communist and socialist parties who negated their status as experimentalists in any sense by becoming visualizers of less than critical utopian ideology.

A second key idea that enjoyed relative popularity among those who rejected capitalist society was that culture and politics had to be in harmony for systemic changes to occur. Political critique, strategies, and tactics were not enough; there had to be intentional experiments in how to live everyday life with different systems of exchange and behavior. The problem at that time was that these spheres of activity remained separate. In 1967, the Situationist call for unification made an appearance: “The critique of culture presents itself as a unified critique in that it dominates the whole of culture, its knowledge as well as its poetry, and in that it no longer separates itself from the critique of the social totality. The unified theoretical critique goes alone to meet unified social practice.”

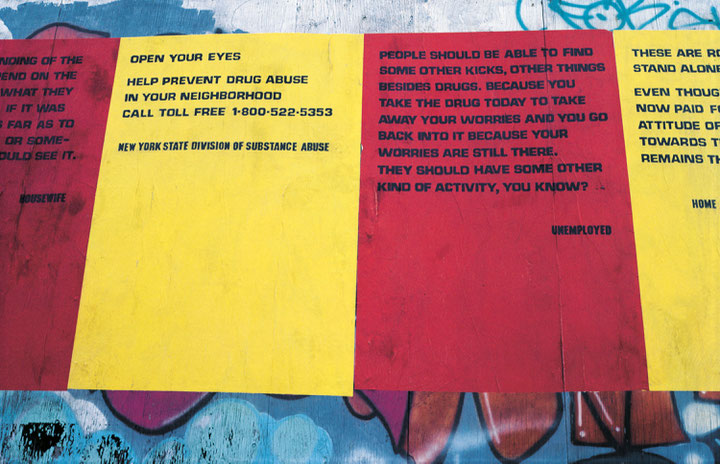

In 1982, this call was echoed by artist collective Group Material in an underappreciated, pivotal work, entitled DA ZI BAOS. One reason this work is so important is that it was unreadable as a specialized product (a subject we will soon return to). This intervention, or perhaps provocation, was installed at the S. Klein building at Union Square in New York City, and consisted of a series of billboard-sized posters with quotes from mostly local people about their perceptions of culture and social relations. Among the quotes is one from Group Material, “Even though it’s easy and fun, we’re sick of being the audience. We want to do something, we want to create our culture instead of just buying it.” While Group Material would go on to create projects that constituted a tour de force in the organization of cultural objects for political ends, they could never escape the confines of art distribution and passive participation. They were not alone, as so many politically active artists struggled with the ongoing contradictions of the avant-garde. While the knowledge concerning the necessity of a new model and thoughts about how this model might look had evolved considerably over two decades, the material conditions to support its manifestation had not.

The Turning Point

In the 1990s, conditions began to change. Notably, the first generation raised with the benefits of the educational reforms won in the 1960s and early 1970s had matured and was entering the cultural field. Within these more progressive curricula and models of pedagogy, a sufficient number came to understand the crisis in knowledge. One central problem was that the Enlightenment model of managing the exponential growth of knowledge through ever-increasing specialization within the division of labor was inherently alienating. People were left floating within their hyperspecialized bubbles, unable to connect with other spheres that could advance their area of knowledge or with those who would be consequential recipients. An additional set of intellectual and creative classes needed to be created that worked across disciplines in order to function as bridges between them. By the late 1980s, the first interdisciplinary generation was beginning to establish a beachhead in the universities and the less profitable or prestigious cultural institutions. What these makers brought to the table was a new sense of what experimentation could be. They identified a new box from which they needed to escape—the boundaries of specialization.

Robert Wilson, one of the great avant-gardists, provides an excellent point of contrast between old and new models of experimentalism in regard to specialization. Wilson claims that his practice began and continues with one simple question, “What is it?” (aesthetic indeterminacy). Anyone who has witnessed a Wilson production knows that he does live by this question. Wilson’s productions are semiotic riots bursting with wave after relentless wave of unstructured meaning open for endless possibilities of interpretation—and, for Wilson, all the interpretive variations are valid and desirable. He actively invites audience members to collaborate with him by completing the meaning of the visual field (a technique very popular with many avant-gardists). For some, this type of theater can be boring or incomprehensible, or simply not worth the labor, but for those who have developed a taste for co-writing, it’s the most satisfying form of art. However, Wilson abandons his question completely in one place—the macro frame of the work is completely stable. Everyone knows they are at Robert Wilson theater production. The specialization of theater is not challenged, even though its conventions are pushed to breaking points.

In the 1990s, the avant-garde model inverted with the interdisciplinarians—they used common conventions for purposes of readability, but removed the frame. For those who desired to move beyond the limits of specialization in order to interconnect nodes of knowledge and invention, the key signifiers of a given specialization became the point of disruption.

Marcel Duchamp had made the discovery of how to undermine specialized discourse in the second decade of the twentieth century with the invention of readymades and reciprocal readymades. An object could be elevated from the mundane to the privileged by connecting it to the appropriate signifiers that are key to a given specialization. In the case of art, the signifiers included a specific architecture, conventional art object presentation (for example, sculpture should be on a pedestal), and an artist’s signature. Even more significant was the theory of the reciprocal readymade, in which a privileged object could be stripped of its key signifiers and thereby reduced to a mundane object (i.e., the use of a Rembrandt as an ironing board). Group Material’s DA ZI BAOS, used this latter tactic to invert the model of the “readerly” strategy of the avant-garde. While the messages contained within the posters were clearly and reliably readable (conventional), the project itself was unreadable. What is it? A political campaign ad, a billboard, a design project, or just a fragment of the pastiche of wheatpasted trash that litters the walls and fences of every urban center? Within this chaotic anti-frame, with all the key signifiers of “art” removed, art and politics could work together without drawing the usual charges of “impurity” or “compromise” that would make the work easily dismissible. This lesson is true not only for art and politics, but also for any other multi-disciplinary constellation. The audience can frame such projects in ways that are meaningful to them, and perhaps even more importantly, in ways that the work becomes significant to them. For the interdisciplinary generation, the question “What is art?” is pointless. They have no castle to defend, and are running away from enclosures into open fields.

The Digital Turn

The proponents of interdisciplinary method, resting in a weak network of cultural institutions, in and of itself did not constitute enough support for a complete split. A technical apparatus was needed that could accelerate the evolution of the model and the movement. The digital revolution in information and communications technologies (ICT) was a co-development that dovetailed perfectly with the refusal of specialization. In the beginning, this new technical foundation was primarily logistical, having two major consequences. The first, and perhaps most important, was that the new ICT supported the creation of a critical mass of objectors. While finding like-minded people on a local or regional basis could be extremely difficult for a movement in its infancy, having a multi-continental pool of people made networks possible that were impossible before. Through the use of listservs, bulletin boards, websites, and email, ideas could be exchanged at a very healthy rate, and virtual scenes and coalitions were formed. The second factor was that most of this could be done for free or at an acceptable cost.

This development also changed funding. While no one location had the financial resources for continuous politically charged experimental research, project development and deployment, or peer exchange, many could find a small bit of investment. When networked, new experimentalists could move to where the resources were. Costs could be distributed so that in addition to the established beachhead, there was a nomadic territory in which the movement could grow stronger. Whether an artist was working in Moscow, Budapest, Rotterdam, Barcelona, Montreal, Seattle, or in the middle of nowhere didn’t matter. There were no more cultural capitals within this sphere of cultural production. This development was liberating in the sense that while traditional cultural capitals and the institutions they contained could still be used and be useful, they were no longer necessary. Everywhere was a site of and for cultural intervention. Legitimation through association with geographic territory began to horizontalize.

As ICT continued to rapidly develop in the twenty-first century, the news only got better in terms of supporting the autonomy of this second model. (The bad news, of course, was that ICT mapped even more efficiently onto the most predatory and oppressive forms of imperial global capitalism.) Greater access to archives and databases, better tools for organization, relative freedom from censorship, cheaper and more powerful software, hardware, and bandwidth, all contributed to freedom from the constraints of traditional limitations. In turn, this supported independent research and amateur explorations into any field. Alternative voices and those that contrast with the mainstream could perhaps be drowned out, but couldn’t be shut out, or stopped. Ubiquitous computing begat ubiquitous research, and this allowed the new experimentalists to move into content areas that were once forbidden by specialization (such as science, social science, and engineering), and to speak to and about these disciplines with some authority.

When describing such bifurcations, an author always runs the risk of presenting a dichotomy that aligns with a purity of value that insists one expression is good and the other expression is bad in some inherent or transcendental sense. What CAE is trying to offer is a grounded context for the value assertions contained in this essay. In terms of pushing the parameters of expression, we applaud the avant-garde and other associated specialists. Who is not happy that there are Gunther Grass novels, Richter paintings, Stockhausen compositions, or Herzog films? We appreciate them as much as the next art lover; however, if one’s focus is the production of culture in order to resists the imperatives of neoliberalism and to develop some alternative to it, then the newly emergent transdisciplinary model is superior in that it has the anarchistic capacity and potential for more contrast, diversity, and independence than ever before (which is not to say it will fully realize all of these possibilities). In addition, any optimism about this development also has specific limits. While we are quite amazed that this model exists at all, that it has some institutional (strategic) support, that it is resistant to elimination via technological means, and that culture and politics can explicitly mix in minoritarian forms, we do not believe we have the tool that will generate the defeat of global capitalism. This model and its varied applications are a small star cluster in the vast black void of corrupt empire. Sadly, we will not be surrendering our pessimistic sensibility concerning the general condition of political economy in the world, but will happily take the small victory that those who stand against the current system have a robust start for productive explorations in another area of social relations that we didn’t have before.