Issue 3/2017 - Das Imperium schlägt zurück?

Defragmenting Omnipresence

The Struggle for Preservation of Soviet Standard Estates

The Cream of Soviet Modernism

For a few years already late-Soviet architecture is the order of the day. After Constructivism, which has inspired some contemporary star architects since they were young, and Stalinist Empire style, introduced to the Western discourse by Boris Groys during the 1980s, today we see the focus shifting to the architectural heritage of the second half of the USSR’s existence. Spanning the period from 1955 to 1991, it is known as post-war Soviet Modernism.

What is notable about the new wave is the interest in unique buildings. Of course, nothing can be captured all at once. Therefore having started with primary monuments, further quests can descend the hierarchy from the main to the secondary, from the centre to the periphery. In the last few years, the architecture of the former national republics is under close scrutiny1. Deeper infiltration into the bulk of the heritage might sound sensible, but this approach goes down a blind alley - the ‘cream’ that can be skimmed off the architecture of the period is very thin. There are only scantily placed masterpieces against the jungle of standard housing and anonymous construction.

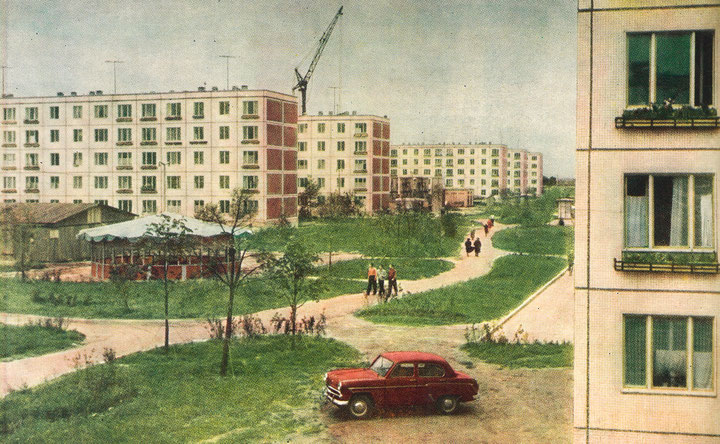

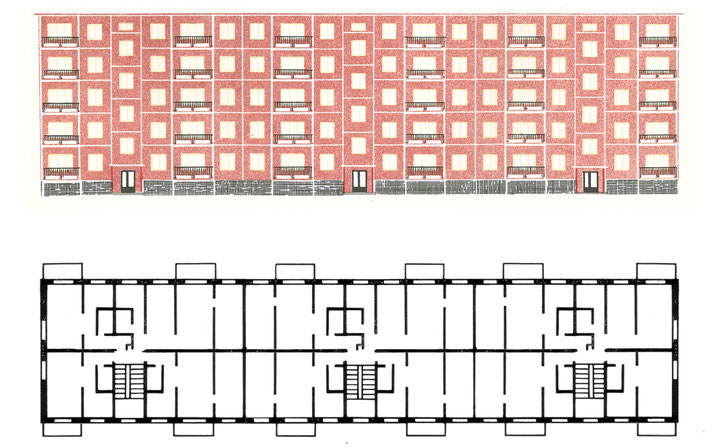

The less architecture there is, the more impressive is the scale of this bulk. Whole cities seem to stem from the same design table. This is especially true of construction during the first half of the 1960s, when the infatuation with standardisation neared its climax. In 1963, 95% of all residential construction proceeded to standard designs. This was not very different for public buildings - schools, grocery stores, cinemas. Even if in rare cases unique schemes were used, they still followed one of the carefully predefined models. Completely obsessed with effective use, devoid of decoration, these structures represented the Functionalist period of Soviet architecture.

The situation started to change after 1969, when the Communist party and the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued a decree, in which they insisted upon transition from quantity to quality in construction. For mass housing, these arrangements implied the pursuit of any means to introduce variation in the layout of standard estates. Architectural design became keen on monumentality. Much attention was paid to the reconstruction of city centres, resulting in impressive ensembles. Large streets regained importance as showcases of Soviet life. Thus conditions were created for the unique architecture that we call Soviet Modernism.

Against the background of this Monumentalism, architectural production pre-1970 faded. And the late-Soviet critics were quick to lay bare its deficiencies. The official reading of the Functionalist period from 1987 held that “The tendency to create simple, laconic structures, in which form follows function, had led to the fact that even those objects, which were built to individual designs, obtained features of a standardised, impersonal architecture. Nevertheless, expressivity of the architectural form in the best works of the time was at a high level”2. But to find itself among the ‘best works’ was indeed a hard task for a building to accomplish. Those that failed were defiled and deemed outdated ‘even before completion’.

Such was the case with the glass box (a popular template during the 1960s) of the VDNKh in Minsk, completed in 1968. Yet, when the city made the decision to demolish the building at the end of 2016, the progressive community expressed alarm. Suddenly, it turned out that the VDNKh is not only great architecture, but a true symbol of the era, whose heritage is so fragile that it can easily be damaged or even lost. And here the paucity of exceptional Functionalist architecture reached out a helping hand. Architect Galina Levina, a daughter of one of the authors of the building, claimed: “The memory is a chain. If some links fall out, misunderstanding of the history and conjectures arise. If such architecture is cleansed from the visual perception of Minsk, we will think of the 1960s as of prefabricated concrete slabs, standardised architecture. And this is not so”3. Eventually, attempts to save the building proved futile. In just two weeks in April 2017 it was turned into a pile of debris. But those who care learned a lesson: today there is a movement on the rise to prevent other modernist buildings facing a similar dismal end. Thus architectural elitism goes into masses in order to become a tool for protecting the urban heritage from the virus of ideological and aesthetic hostility towards Modernism, and its Functionalist decade in particular.

Standard Housing in Revolt

Standard housing in its turn seems to have nothing to hope for. Its architectural qualities are admittedly low; nobody is going to stand up for it. And the only trite argument, namely that the Khrushchev’s policy was the only possible way of solving the exigent housing problem in the country, does not look salutary. Instead, it stresses the temporality of the policy, whose advantages are obviously a matter of the past.

However, as practical evidence has shown, standard residential estates do get support as soon as they appear under threat of injury or demolition. Suddenly it becomes clear that the Modernist habitat has its own distinct qualities - human scale, greenery, decent social infrastructure, location. Since 1991, urban infill has become a scourge of that idyll. Countless cases arise in former Soviet cities, when the unbuilt space of the estates is filled with new high-rise development. This provokes the indignation of local inhabitants, who are concerned about contraction of green areas, increase of noise, rubbish, and the load upon infrastructure, such as social amenities and transport networks.

Even more eloquent is the situation around the reconstruction of mass housing of the late 1950s – early 1960s in Moscow. The program for a gradual substitution of shabby 5-storey residential buildings with new standard blocks in the Russian capital was conceived before the collapse of the USSR, but fell mainly upon the 2000s4. A triple increase in density of construction due to a larger number of stories allowed developers to both resettle tenants from the old slabs into new buildings and gain profit from selling remaining flats. This program, which due to the crisis of 2010s has dragged on until today, assumed demolition of only those slabs that had been defined as unsuitable for modernisation. In the spring of 2017, however, the Mayor of Moscow, Sergey Sobyanin decided to greatly expand the reconstruction program to cover all 5-storey development of the Functionalist period in the city5. Since the remaining housing stock of the kind is about 4 times larger than what has been already demolished6, the realisation of the proposal cannot but stretch for several decades. With this in mind it is tempting to surmise that a different logic is hidden behind the initiative than the official claim to provide Muscovites with better dwellings. A likely scenario is that the reclamation of the estates will proceed in the order suggested by developers, although the authorities have always denied that agenda. Still the policy caused mass protests in the streets, gathering displeased citizens from all sides. The protests showed that social interests are greater than enmity towards deficiencies of the standard environment. Despite the monotonousness, deprivation and low-quality housing, it is more valuable than what may come to substitute it.

The appeal to social and cultural aspects while considering the preservation of modernist estates of the 1960s is a trick in Kuba Snopek’s book Belyayevo Forever7, a speculative attempt to find intangible qualities in a standard environment that drastically lacks architecture. Extrapolating qualities from a single standard building to whole residential estates, the author convinces us of their spatial qualities. Yet he is compelled to use ‘anti-architectural’ keys to open the secret door.

Lifesaving Reality

Consequently, the heritage of the Functionalist period in Soviet cities is embraced from two sides. On the one hand, architects are trying to defend unique objects neglecting standard development. On the other hand, this very standard development gets protected by social discontent. How effective the measures are will be clear later, since the awareness of the problems is too fresh to judge. But for the time being there is not much to be proud of.

Anyway, the architectural heritage stands out here as a quality in itself. More important, however, is that two conditions indicate structural conflicts across the former USSR, both between regions inland and between former republics. The common Soviet past is processed slowly with immense efforts. The most obvious example is Ukraine, where the de-Sovietisation Law leads to extirpation of Soviet symbols, carrying off architecture as well. Clearly this is a reaction to the present war with Russia. But neither it is calm in Russia itself. The afore-mentioned reconstruction program in Moscow does not have analogies in other cities of the country. In most regions, especially in those with a rough climate, the deterioration of mass housing blocks is definitely higher. And if it is true that their condition in the capital is problematic, then elsewhere it should be bordering on a catastrophe. When dilapidated buildings start indeed to fall apart, social unrest will be of such an order that the current protests by ever-displeased Muscovites will seem just a prattle.

The situation seems daunting. The gap between architectural interests and problems of standard environment reflects the chasm in grasping the true problems. Bridging that gap may help see deeper into them and even offer the conditions to start acting. That necessary bridge – predictably enough – is mass housing. Yet it may prove successful only if it draws architects’ attention. Of course, mass housing of the early 1960s is not attractive: its scale was overwhelming, unification reached its limits. National interests were out of the question; the differences in composition of estates were caused by climatic peculiarities only. The most rapacious was large-panel housing: since 1959, hundreds of factories for production of the I-4648 construction system spread across the Soviet Union: from pro-European Estonia to rather neutral Belarus to Kazakhstan and the Far East. These factories manufactured identical buildings. Architects had some freedom in arranging housing estates from these standard blocks, but components of the residential environment and methods of construction were always the same. As a result, most former Soviet cities, representing various ideological worlds today, include identical fragments of urban fabric.

And still, standard estates are intriguing and preserve an amazing potential, rooted exactly in their omnipresence. Nobody is capable of disposing of this environment. The Ukrainian de-Sovietization Law may exterminate symbols of the era, its unique architecture, but cannot really interfere with Soviet mass housing estates. Even in Moscow with its enormous capital, the eradication of the standard environment of the early 1960s is approached with scepticism, and will probably last forever. There is no need to state that the same heritage in the rest of the former USSR – in fact tens of times larger than in the capital – is living its own life.

Given its ubiquity, mass housing – unlike the best architectural works of the time – is not the mirror of the epoch, but its immediate reality. It is an incubator of a 'Soviet man'. This man created the environment, and the environment shaped him in response. It is there that he is reproduced until the present day, fifty years later, no matter what impulses there are to renounce any affiliations with the past. Thus, the fragments of the identical urban fabric do and will remain the most unifying elements in an increasingly more fragmented space of the former USSR. It is those fragments that we will have to find and focus on in order to remain in control of the situation. And without the architect’s attention, this is impossible to achieve.