Blockchain has recently become one of the most discussed technologies, despite its complexity. The promise to become the “next big thing,” is grounded on being the technology that underpins cryptocurrencies, including the famous Bitcoin. It is hard to exemplify Blockchain, as it has a few key technical complex and crucial aspects, but basically it allows digital information to be distributed, and not just “copied,” which means that each individual piece of information (data) can technically have only one owner. So it basically allows information to be distributed over the networks, maintaining “forever” its original form, allowing authenticity and reliability over time, which is probably the weakest point in the whole digital media infrastructure. The promise of transforming the reliability of digital in a reliability typical of the physical media has potential enormous consequences, especially economical ones. But as every technology that reaches the global and universal status, it has a so-called “Janus face,” as it structurally guarantees the integrity and so authenticity of information over time, which simultaneously means direct control over the information, being completely trackable. Ethically, these can be virtuous in some domains, not in others, as they might completely dismiss privacy in certain respects. And even if it is a prominent technological development, as for the first time it’d namely enable completely trustable and incorruptible financial transactions, it is not clear if it will benefit or potentially harm the arts.

Most of these aspects have been discussed in the seminal book Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain edited by Ruth Catlow, Marc Garrett, Nathan Jones & Sam Skinner. Especially Garret and Catlow (both founders of the Furtherfield online platform and directors of the Furtherfield Gallery & Commons space) have developed over the last years a significant knowledge on the relationships between the blockchain and the arts.

The book itself hosts an experiment called Finbook, which links the included essays to a financial trading portfolio. The readers are encouraged through a QR code to rate the chapters, assigning them “value tokens,” while some bots (“FinBots”) are assigning values themselves, trading the tokens in a “speculative pastiche.” This process reflects on one side the current “atomization” of content, with the consequence of creating publishing sub-products (the chapters) from which to profit. On the other side, it also exasperates the competitive level of publishing, down to the chapter size.

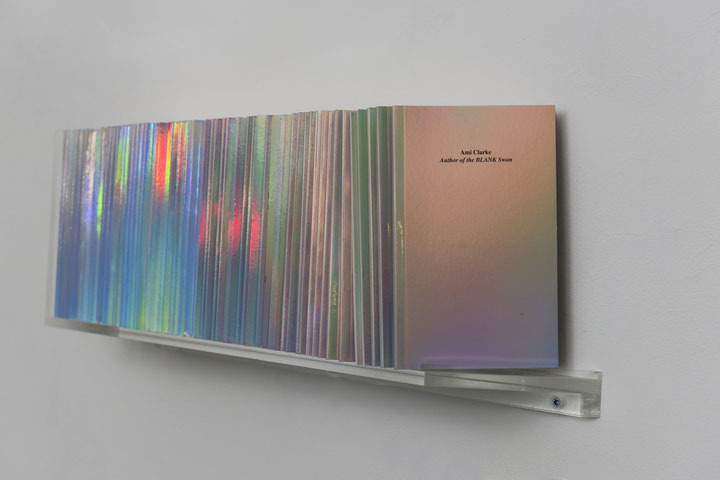

The experiments using blockchain in text production and publication can also refer more to concepts than to the current technology. A very conceptual approach has been taken by Ami Clarke, a curator and artist who has dedicated a lot of energies to enable a public discussion of the relationship between Blockchain and arts. She materializes a response to the book of the French Lebanese financier and philosopher Elie Ayache, titled The Blank Swan, where he suggests (in Chapter 4, “Writing and the Market”) that “writing” is like “pricing” in the market of derivatives, drawing on Jorge Luis Borges story of “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”, where he talks about a fictional writer and critic who spends his time writing chapters of Don Quixote, several centuries later, with exactly the same words. Then Clarke re-writes one word after the other the Chapter 4, publishing as Ami Clarke: Author of the Blank Swan. In a performative writing act which recursively refers to Borges, but also to a few conceptual artists “reworking” artworks by other artists, what she’s quietly and loudly at the same time stating is the crucial function of the “time-stamp” in the Blockchain technology that carves in stone the content become immutable. She describes then an “equivalence” in the capacity to write in the future.

To already implement writing practices in the blockchain technology is the Civil journalist platform, based on the Ethereum cryptocurrency, developing their bespoke one, the CVL token (and so currency). Their aim is to become a place where the writings are both funded and whose success funds in return the platform itself. The articles themselves are hosted on a blockchain, so their integrity is equally guaranteed. In their claims they mix the micropayments enabled by the crypto-economies with a response to the trust crisis generated by the waves of fake news in all the major social media platforms.

Here the “trust” emerges again in the blockchain discourse, then, as both a primary need to use a platform, a rare virtue in public writing, and a technological core point of the Blockchain itself. In this respect, we can easily relate it to the major efforts in the release of protected documents like the Wikileaks ones, and how we “trust” them mainly because we trust the infrastructure releasing them, instead of questioning the authenticity of their documents one by one.

Finally, the Blockchain experiments with text can include some bold claims, like PWR studio does for their Txtblock affirming that “the (blockchain) block is the successor to the book.” They enhance that the block-identifier, is “directly tied to the information it identifies”, so pointing uniquely to it, and being unmodifiable, so they solicit customers who wants to commit “to eternity” about their writing. Available only as pure text (no typography), and also based on the Ethereum platform, Txtblock calls, as most of the blockchain efforts, on decentralization as the most important value, fighting the current online giant pervasive invasion of our privacy and data.

The blockchain sounds extremely appropriate to our times. Its decentralization is luring despite the complex technological level and it is technologically advanced, but based on an always-on technological infrastructure, which is resource-expensive by design. It is placed at the verge of contemporaneity, showing how the search for equality through technology has a price to pay. But then we might wonder: aren’t we then ultimately delegating the trust to the machine? Do we really need immutable texts online, or we’re wasting a sensitive amount of resource just because we’re weakening our ability to develop trust? And do we need to empower a whole technological infrastructure for what has traditionally worked without disastrous faults till now, just on print with verifiable registers (the ISBN and ISSN numbers) and people legally responsible? These are still open questions.

Catlow, Ruth / Garrett, Marc / Jones, Nathan / Skinner, Sam (eds.), Artists Re: thinking the Blockchain. Liverpool University Press 2017.

Rasmus Svensson & Hanna Nilsson (PWR), The Block is the Successor to the Book: A publishing proposal (Nov 17, 2015), http://rhizome.org/editorial/2015/nov/17/the-block-is-the-successor-to-the-book-a-publishing-proposal/

Ami Clarke, https://www.amiclarke.com/author-of-the-blank-swan-2

Civil, https://civil.co/