Issue 1/2019 - Post-Jugoslawien

On Solidarity in Time

In Front of an Empty Wall, Looking at a Lost Image

To be contemporary means to live with time and in time, to live within one’s present; but it also means sharing the particular moments of time of both the past and the future. It assumes certain solidarity in time.

Living in the present moment, in which the “parental” promise of historical progress and a better future waned, we are provided with an illusion that we live in the era of an absolute chrono-democracy, in which all the historical moments seem reachable and easily accessible, ready to be performed, experienced, consumed, and recreated. Our memories are simulated and mediated, assembled from various pasts that are spectacularly presented in reality-show-like digests on dedicated History Channels™. Everything, including the World Wars, now runs again—and “this time, in color.” The past has become the new horizon of hope, a playground for political fantasies—recreated, rewritten, re-envisioned. Since the 1990s, this terrain of playful imagination has expanded into a fashion of historical revisionisms, evolving into the contemporary era of production of alt-facts and post-truths.

Is it possible to express solidarity in time beyond mere commemoration?

The historical moment of solidarity of the people of Yugoslavia with the people of Latin America that Darinka Pop-Mitić and myself are dealing with has the status of a “lost object.” Not only is the material evidence of this “precarious moment” scarce and spread around scattered archives, but also the solidarity itself has slowly paled and disappeared, both as project and affect.1 The story of the solidarity of the Yugoslav people with the people of Latin America could be easily forgotten if not supported by a certain affect; the story itself is non-sustainable in crude historiographic readings and the mandatory categorization of institutional archives—the name of the muralist brigade was constantly changing, its participants came and went, murals disappeared over time and were refreshed, the political and institutional context paled and was refreshed… But, refreshing the memories of the event and adding to it commentary from a historical distance makes this story truly contemporary—contemporary in the sense that it is a struggle in and with time, the struggle that is inscribed in the very meaning of the word (contemporary: con—with, tempora—time). The very term “politics of historicization” in the contemporary context assumes such struggle in time, it is the struggle for a politic that deserves the future—and therefore deserves “to be included” in the past, to be remembered historically. Solidarity in time cannot be achieved simply through a counter-positioning vis-à-vis the reproduction of the contemporary, ventilation of the present or falling into the black hole of supernow, but through the historical approach to contemporaneity2 in which both the past and the future are becoming sites of struggle.

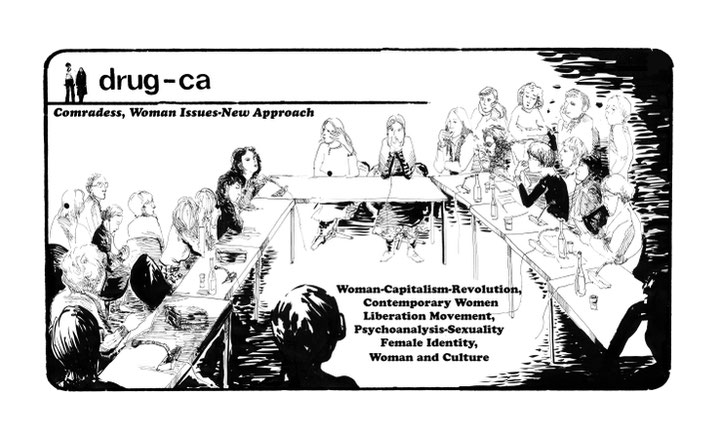

The project of the solidarity of the Yugoslav people with the people of Latin America was part of the Tribune Program of the Student Cultural Center (SKC) in Belgrade, which was dedicated to political theory and social movements. In the words of its editor, Milo Petrović, the tribune “offered a site of free-minded public speech, intellectual debate, and social activism.” Between the mid-1970s and the mid-1980s, the Tribune presented several conferences and events: Nedelja Španije (Week of Spain) in 1976, coinciding with the end of Franco’s dictatorship; the Week of Latin America in 1977, examining the anti-colonial struggle of various militant guerrilla movements in the era of corporate neocolonialism, and explicitly posited via its subtitle as an event of “Solidarity of the Yugoslav people with the people of Latin America.” Further, the first “women’s questions” outside the Western context were posed during the conference Drug-ca žena (Comrade(ss) Women) in 1978; and an event dedicated to militant revolutionary Chilean cinema—Druga nedelja Latinske Amerike (Second Week of Latin America)—was held at the beginning of the 1980s. New movements in psychiatry (or, more precisely, the positions and attitudes of anti-psychiatry) were discussed in 1983, while events in 1984 were dedicated to the critique of recent Yugoslav politics that would slowly lead to the dissolution of the federation.

It is important to mention that the SKC was operating at the time as an alternative institution that opened up its space to experimental art and exhibition practices, to social activism, and to critical intellectual developments. It was self-produced as an institution-in-movement, or institution-movement, growing out of the student and workers’ protests of 1968 and continuing that movement from the inside as a critical wave, supported by the international flux of artists, intellectuals, and activists.3 Many people participated in the SKC’s activities without being part of its formal institutional structure, working instead in the same space within self-organized communities, and often influencing the regular program through editorial boards, councils, and ad hoc groups formed for the various initiatives. Further, it was a place where people actually lived: young artists and intellectuals spent time together in proximity and exchange, and this togetherness resembled the functioning of an “alternative university,” or of certain self-organized teaching-learning practices.

From the perspective of exactly three decades later, Petrović reflects upon his perspective on con-tempora-ry in the context of his engagement in the Tribune Program: “We wanted to be in touch with the problems of the world, the problems of our times—to discuss the developments in intellectual thought, in artistic practice and socially engaged work. We wanted to host programs and people who reflected our epoch […] We thought that it is good to live with our times.”4

This event of solidarity of Yugoslav people with the people of Latin America was one crest of the wave of the world’s solidarity with Chile, after the fall of the government of Salvador Allende and the beginning of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. The decade of the 1970s was the era of the worst military dictatorships in Latin American countries—the time of the fall of the first democratically elected Marxist president in Latin America (Allende), and the time when the generals of Argentina were waging the infamous Guerra Sucia (Dirty War) against its population, exterminating political enemies by committing such acts as throwing people out of airplanes. This was the time when many political refugees fled to Europe and, along with assistance in the wider sense of social care and security, within certain circles also received solidary help in promoting, and agitating for, their political cause.

Since his early youth, Petrović was interested in anti-colonial revolutions. As a young high-school student in the small Bosnian city of Bijeljina, he read books about Algeria’s Front de liberation national (National Liberation Front), among them La Question by the journalist Henry Alleg, describing the methods of torture used by French paratroopers on revolutionaries, which made a significant impression on Petrović, and influenced his later political and intellectual interests. After the shameful killing of the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Petrović organized a program of solidarity with Congo and participated in street demonstrations in Bjeljina.5 His individual political consciousness and social engagement were part of the larger cognitive-political infrastructure that Yugoslav socialism and non-alignment provided, and that was conveyed into the fields of political education and practice throughout the country, not only in the metropolitan centers and capitals of the various Yugoslav republics.

Two years before the Week of Latin America took place, the book Historical Roots of Non-Alignment,6 by Edvard Kardelj, the prominent Yugoslav politician, revolutionary, and theorist, was published. In the Yugoslav context, often articulated in Kardelj’s writings, non-alignment was not understood as a completed project, but rather as a long-lasting political process through which each country, as well as the movement as whole, would overcome all the residual effects of the colonial epoch and internal social conservatisms, and progress towars developed socialist and communist societies (as outlined by the first Non-Aligned Movement Summit held in Belgrade in 1961 following the Afro-Asian conference in Bandung 1955). Although non-alignment, in its linguistic-political substance, assumed an overall rejection of any alliance with either of the political blocs that maintained the Cold War division of the world, an important aspect of such positioning is summarized precisely in Kardelj’s thesis, according to which the bi-directional negation of the power blocs does not imply reaching a point of ideal “equidistance” from the existing centers of power, but is actively countering the power politics as such.7 Although the official politics of non-alignment was not explicitly central to the event of solidarity of the people of Yugoslavia with the people of Latin America, it was precisely that socialist context, and the alternative critical institutionalism developed within such a context, that enabled the large gathering during the Week of Latin America. In other words, non-alignment was creating a framework upon which such a “picture of the world” could be mounted.

The Non-Aligned Movement at that time was slowly confirming its political role in the international “hegemonic commons” embodied in the institution of the UN, through practicing realpolitik and maintaining the global balance of forces. In this sense, it differed greatly from what the young guerrillas in Latin American countries were demanding and were striving for. The heyday of the revolutionary impetus of the Non-Aligned Movement in the Yugoslav context was slowly vanishing. Although Josip Broz Tito was one of the first international politicians to support Allende’s government, according to Petrović: “at this time, the Yugoslav government was shifting toward pragmatic solutions. Tito had consolidated himself as an international politician who changed his position in the direction of defense of what was being achieved instead of the revolutionary critique of the existent. Tito’s position became the defense of the existent. And this will later lead to the clashes within the [Non-Aligned] Movement between Tito and Castro. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia was no longer being led by the young people for whom the field of the possible was opened, but by the people who conformed to realpolitik.”8

Unlike the trajectories of realpolitik of Yugoslavia and non-alignment in the mid-1970s, the SKC Tribune Program regularly collaborated with liberation movements from Latin America, Vietnam and many other places. The Week of Latin America did not proceed without its real-political frictions, and Petrović remembers that the tribune received complaints from the Peruvian and Argentine embassies for bringing to Belgrade, and giving space and attention to, the political enemies of then-current regimes.

Petrović emphasizes that the meeting in Belgrade, within the “extra-territorial” space of Yugoslavia, was important for the (self-)building of community and the exchange of the intelligentsia in exile, and that many participants of the event claimed that for them and their struggle, this was the most important meeting of that year:

“I remember the opening of the Week of Latin America—more than five hundred people were in the auditorium, and when the singer and author Chango Cejes was about to start singing the song Hasta Siempre, he said that he would like to sing it without a microphone and invited Roberto—the brother of Che Guevara—and other participants and the audience to join. […] And I remember this excitement of the people throughout the big hall of SKC being almost palpable.”9

Cultural programs were discussed through the focus on the notions of engaged art practice and tight connections between artistic and revolutionary acts.

The Brigada Salvador Allende painted three large-scale murals10 with solidary support of students of Belgrade’s Faculty of Political Science and Academy of Fine Arts. Such exchange through the processes of working and discussion was characteristic of the SKC as an “alternative university”—the metaphor to which many program organizers, including Petrović, would later refer, emphasizing that their programs were not merely based on exchange and mutual informing, but on collective political Bildung.

We can trace the activities of the brigadistas through archival television footage recorded on the painting11 locations during the Week of Latin America events. Interestingly, in the context of “engaged art,” militant practice, and guerrilla “war by other means,” we hear only the first names (or perhaps their guerrilla nicknames) rather than the full names of the artists; the latter would be characteristic of artistic (self-)representation and individual authorship, for all that is officially recognized as art today.

Alfredo explains that the Brigada Salvador Allende was founded in Milan in 1975: “It was founded by the members of the Socialist Party in exile who have recognized the need to express their solidarity through culture. We have chosen murals as a form of support to Chilean people. There are eight comrades in the brigade. All are members of [the] Socialist party. Five of us are here. We came from different professions—this comrade here is a student, and has a scholarship stipend. The other one is a social worker. The third one, she is a worker. I am teaching Spanish at the Pavia University in Italy. My colleague here is teaching guitar.”

Gabriela—another muralist and member of the group—emphasizes the material and political support for Chilean resistance that the group takes as one of its primary goals: “We are mostly financed by political organizations that invite us. The whole sum goes to the Party and resistance forces. We do not take anything. Sometimes, we give political contributions, like now in Yugoslavia.” Woman X, who remained nameless, continues: “The mural itself consists of four elements. The first one is people’s rule and is depicted through the joyful memories and happiness, through flowers and factories. The second one is repression, torture, prisons, and death. It is done by military junta and agents of American imperialism. Then we have a fist as the representation of solidarity. It holds [a] Yugoslav flag. And then we have the struggle that is depicted by a man with a rifle. Then our flag, and a fist holding and waving the red flag. Only after this struggle can the future exist, the socialist, glorious future projecting beyond our revolution in Latin America towards global unity of people.”

As is generally the case with street art, its existence is temporary, and it is often connected to a specific moment and a particular situation. None of the brigadistas’ murals were preserved—over time, they paled then vanished, in parallel with the fading of the official ideology of socialism, non-alignment and revolutionary struggle—and its replacement by the currently prevailing blend of a neoliberal capitalist economy with global “alt-right” ideology. The story of the Brigada Salvador Allende in Belgrade and the Week of Latin America was remembered in the 2005 project On Solidarity, initiated by artist Darinka Pop-Mitić. For it, she refreshed the colors on the remnants of the mural on the wall of the SKC, expressing by this act her solidarity in time with the events of people’s struggle for decolonization and liberation, with a particular historico-political moment in Latin America, Chile, and Yugoslavia in the 1970s.

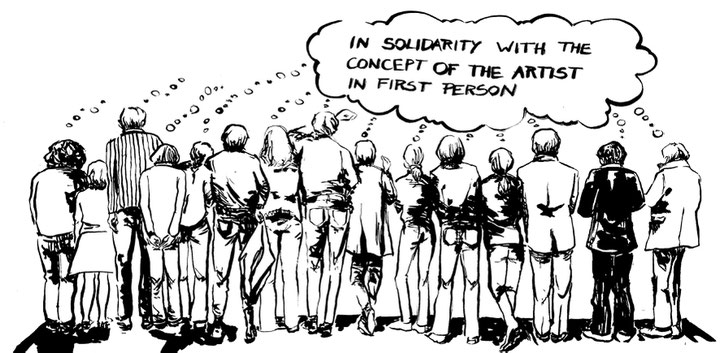

What is interesting in a deeper examination of solidarity—and what offers a more complex picture of it—is the fact that SKC had at that time developed rich artistic programs, cultural politics/attitudes, and communities who worked together to develop the language of New Art as part of the gallery program—but in 1977, none of the usual SKC artists joined the program or the execution of the murals. In other words, contemporary artistic solidarity had not been achieved in the then-present moment as the labor of present-ism, but in time and through time, through the labor of history. This also shows that solidarity in time does not have to be immediate, or even immediately recognizable, but might also take time—it can be durational and reach other, unexpected addressees who can reidentify and newly ally with the historical contemporary.12

In her artistic statement, Pop-Mitić comments on this labor of (art) history—on what is singled out as valuable and received new (precious) object status in the international memory, becoming part of respected archives and collections; and what is left to historical-political oblivion to become the “lost object” (eventually “restored” by contemporary artists or curious art historian).

The inside of this institution, the SKC, is a conceptual art scene, while its outside is a “Third-World” mural made in collaboration between an artistic brigade and the students of the FLU [Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade], an obvious propaganda artwork. The framework, the “frame” of the entire conceptual art scene in the SKC, is in a way precisely this mural, but on the other hand it is exactly this mural that was both badly documented and left at the mercy of the ravages of time, which fragmented it until the only thing left were the giant heads that always frightened me when I was passing by the SKC building as a child. Chesterton has the following aphorism: “Art consists of limitation. The most beautiful part of every picture is the frame.” The mural Solidarity is the “frame” for our conceptual art scene.13

During my research of the politics of historicization of the SKC, as well as exhibition history within and beyond its alt-institutional walls, I pointed to the notions of heterogeneity, cohabitation, and lamination of different but mutually interconnected cultural-political positions and voices.14 As Pop-Mitić underlined, the project concerning Latin America and the works of the Brigada Salvador Allende are examples of a certain politics of art addressing a different poetics in comparison to what was happening in the gallery program of the SKC, which at the time assumed a variety of artistic and political positions but mainly dismissed “explicit political activism” and “traditional pictorial expression.”

The New Art Practice has put the emphasis on language, the language of art, expressing itself through negative, non-representational gestures, different uses of the gallery space through showing and not showing, through non-representational exhibiting. For them the “traditional pictorial” belonged to a system of universal artistic values that would always preserve the reproduction of the bourgeois institution of art that they were trying to surpass and destroy. Thinking of art and politics, or rather about the politics of art, for the representatives of the New Art Practice meant revolutionizing the language of art—a shift from the mimetic function of art and its obsession with the questions of representation, to ideological apparatuses that establish criteria for the production and evaluation of art.15

Pop-Mitić’s refreshing of the colors of the Solidarity of the People of Yugoslavia with the People of Latin America mural offers a perspective from which we can think of what has happened since its execution—on one hand showing the forgotten artistic act of political agitation against colonialism, and on the other showing implicitly (or delegating the conclusion to the viewer) what became of value in the contemporary and of interest to collectors and to the art world of today (“our Conceptual art scene”) … Exhibiting the mural again, against all the odds of contemporary alt-right politics, meant showing constellations in time and of time that go beyond the mere commemoration of “glorious times of revolution and international solidarity.”

Reexhibiting the mural by the Brigada Salvador Allende also shows that the SKC’s form of institution-movement is reflected precisely in its unwillingness to settle itself on the one side of a binary opposition or division of cultural space into official art and alternative art—a partition line that has often been used as the principal epistemological tool in the more recent cultural histories of the countries of real socialism.16 Representational and non-representational approaches, popular and experimental attitudes, political propaganda art, art in the form of thinking, and formal interventions within the language—all these different, sometimes contradictory positions coexisted in the same space. The space of the SKC was self-produced precisely through “surpassing,” but also embracing and embodying various contradictions of being movement-institution, self-organization-institution, or critique-institution. And it is precisely those dualisms and contradictions that appeared as the very “substance” that eroded the firmness of the walls, the enclosure, isolation, and self-sufficiency of a classic institutional venue with regard to everyday life and building sociality “from below.”

[1] For Rasha Salti “solidarity appears/operates as the emotional side, affective side of the common.” Salti, Glossary of Common Knowledge, Ljubljana; European museum confederation L’Internationale, June 27–29, 2016, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, http://glossary.mg-lj.si/narrators/rasha-salti/56/.

[2] Contemporaneity seen historically counts on the fact that we are always building the past and the future from the present moment, from the position of today.

[3] The SKC was a result of the political activities of a group of young intellectuals who led the protest and the student union. Control over the building of the State Security service (UDBA), which was undergoing reconstruction and was located in the center of Belgrade, was given over to the student union at the very end of the 1960s; of significance is that this happened after the student protests, which ended with the symbolic, ambiguous, and equally assimilative words of Comrade Tito: “The students are right!,” signaling, in fact, that the rebellion of 1968 was over.

[4] From interviews with Petrović used in the television special “Alternative University” (recorded 2007, including the original archival footage from 1977), courtesy of Bojana Andrić, editor of the Trezor series, Radio Television Serbia.

[5] From my conversation with Petrović, May 2, 2017, Amsterdam.

[6] Edvard Kardelj, Istorijski koreni nesvrstavanja [Historical roots of Non-Alignment] (Belgrade: Komunist, 1975).

[7] More about the concepts of political peace, active neutrality and countering the power politics in Jelena Vesić, Rachel O’Reilly and Vladimir Jerić Vlidi, On Neutrality (Belgrade: MOCAB, 2016).

[8] From my conversation with Petrović, May 1, 2017, Amsterdam.

[9] From interviews with Petrović, “Alternative University.”

[10] One mural was on the external wall of the SKC, overlooking the inner courtyard that was used for informal gatherings and as the meeting point of young people visiting the center’s programs; another was on the plaster tiles inside the SKC; and a third on the wall of the cafeteria of the Faculty of Political Sciences.

[11] From interviews with the Brigada Salvador Allende, “Alternative University.”

[12] My colleagues and friends Ivana Bago and Antonia Majača discuss this expanded understanding of solidarity, of solidarity in time, under the term “delayed audience”—a term that opens an inverse perspective to the neoliberal institutional pressures of audience-targeting, counting the numbers and conforming to the allegedly immediate response of the inhabitants of the present. Ivana Bago and Antonia Majača, “Prvi broj (The First issue) / Acting Without Publicising / Delayed Audience,” in Parallel Slalom: A lexicon of non-aligned poetics, Bojana Cvejić and Goran Sergej Pristaš eds. (Belgrade, Zagreb: Walking Theory – TkH and CDU – Centre for Drama Art, 2013), 252.

[13] Quoted from Darinka Pop-Mitić’s artist statement, “On Solidarity (Interview with Darinka Pop-Mitić)”, in Jelena Vesić and Zorana Dojić, eds., Political Practices of (post) Yugoslav Art: Retrospective 01 (Belgrade: Prelom kolektiv, 2010), 263.

[14] Research “The Case of Students’ Cultural Centre—Belgrade in the 1970s” (with Prelom Kolektiv), 2007–2009, https://www.prelomkolektiv.org/eng/PPYUart.htm ; see also “Parallel Chronologies: An Archive of Eastern European Exhibitions” (with tranzit.hu), 2014–2015, http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/essays/jelena-vesic

[15] The cultural-political project of the New Art Practice was most manifestly presented by the counter-exhibition October 75 discussing art and politics from the viewpoint of New Art. See Jelena Vesić, “Oktobar 75—An Example of Counter-Exhibition (Statements on Artistic Autonomy, Self-Management and Self-Critique),” 2015, http://tranzit.org/exhibitionarchive/oktobar-1975/.

[16] In various overviews of art in Europe before the fall of the Berlin Wall, we find the epistemological division reflected in two binomials or binary oppositions that consistently appear in studies on Eastern Europe and in new art histories observing the art from the countries of the former “socialist bloc.” The first binomial consists of the concept of totalitarian art, which groups together Socialist Realism, Nazi-Kunst and Fascist art and opposing them to the concept of free art, which encompasses various avant-gardes and modernisms, as well as contemporary art. The second binomial opposes the concept of official art, which evolves in accordance with the dictates of the authoritarian state, with that of alternative art, which stands in formal opposition to the state, “hiding” on the margins of public life in the “dark spaces” of alternative scene, in the (semi-) privacy of artists’ apartments, or somewhere in the remote wilderness of nature.