“The creative act is not performed by the artist alone,” stated Marcel Duchamp at a convention in Texas in 1957, thereby calling into question the modern conception of art based on the myth of artistic genius1 and acknowledging the key role of the spectator instead. The spectator's key role is even more in evidence today: contemporary art's very functioning is based on the premise that art objects presented in exhibitions are to be interpreted from the spectator's point of view – to the point where the latter seems to take precedence over everything else. As Suhail Malik writes: “The artworks and the discursive formulation of contemporary art – objects, events, performances, images, press releases, reviews, magazine essays, auction catalogues – stylize and configure a correlationism in how art is to be taken by its audience. Contemporary art appeals to its addressees to determine the art in their own terms, including the disagreement between viewers that is the best ideal ‘democratic’ result. Artists have an ‘interest’ in this or that; the artwork or exhibition ‘explores,’ ‘plays with,’…. such and such topic. No more definitive or precise an account can be permitted at the cost of reducing viewers' own capacities to make their call on the art”.2

In this essay, I want to look at how art can be envisaged not in terms of reflecting human agency and subjectivity but as a means of gaining access to nonhuman subjectivities. More broadly, I will show how artists, philosophers and theorists are increasingly exploring the question of how to grasp and define agency, sentience and subjectivity non-anthropocentrically, that is, by exploring these terms in relation to objects, plants, animals or machines.

We might start by considering the work of the philosopher Quentin Meillassoux. Meillassoux contests what he calls correlationism, defined as ‘the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from the other’,3 or in other words, the assumption that we cannot know anything that would be beyond our relation to the world. Meillassoux refers to ancestrality, meaning any reality anterior to the emergence of the human species, and asks how correlationists can interpret the ancestral statements advanced by science.4 Building on Meillassoux’s reasoning, Steven Shaviro explores the idea of non-correlational thought, a nonphenomenological thought or sentience, which is nonintentional and noncognitive and does not recognize or interpret anything, thereby eliminating the ‘human element’ in thought.5 Object-oriented ontologist Graham Harman, on the other hand, claims that everything is an object, that humans are but one type of object among others and that to understand the world we need to take into account not only human-to-human and human-to-object relations but object-to-object interactions as well. In his book Alien Phenomenology, or What It's Like to Be a Thing, another object-oriented-ontologist, Ian Bogost, expands on these ideas, noting that we can only talk about bats, for instance, by means of subjective and anthropomorphic analogies and metaphors.6 In other words, we can understand the effects of the high frequency vibrations voiced and heard by bats, but that has nothing to do with understanding what it is like to be a bat. Bogost also asks how we might understand object-object relations, for example between a bat and a branch, and suggests that we cannot eliminate the distortion of human perception. These are some of the ways in which speculative realism attempts to access the nonhuman.

New materialism also takes a non-anthropocentric stance. Whereas object-oriented ontology claims that everything is an object and that objects are ultimately unknowable, new materialism questions the hierarchy of human over nonhuman by viewing the world in terms of continuities between subject and object. Take philosopher and theoretical physicist Karen Barad whose theory of agential realism questions the very distinction between human and nonhuman by highlighting the entanglements between social and natural agencies. Barad writes: ‘It is important to note that the 'distinct' agencies are only distinct in a relational, not an absolute, sense, that is, agencies are only distinct in relation to their mutual entanglement; they don't exist as individual elements.”7

Theorists from other disciplines adopt similar standpoints. The anthropologist Tim Ingold’s view of agency echoes that of Barad when he writes: “Forms of things are not imposed from without upon an inert substrate of matter, but are continually generated and dissolved within the fluxes of materials across the interface between substances and the medium that surrounds them. Thus things are active not because they are imbued with agency but because of ways in which they are caught up in these currents of the lifeworld. The properties of materials, then, are not fixed attributes of matter but are processual and relational.”8 For Ingold, “making” can give us a grasp of matter – making in the sense not of realizing a pre-defined project nor of transposing one's own ideas on objects, but of attending to the growth and development of matter's potential and participating in processes that are already ongoing9 – in other words, adding or relating to these processes on their terms rather than ours.

If Ingold can be said to extricate things from the spectatorial framework by having us relate to them on their terms, other researchers have been thinking along analogous lines with respect to animals. Take the Swiss zoologist Adolf Portmann (1897–1982) who in the 1940s put forward the idea that the animal life is not determined only by the need to survive, but also by the need to manifest specificity visually. The colored motifs displayed by certain animals are thus organs for being seen, in the same way as the digestive system has organs. That said, appearance does not always imply a subject capable of perceiving it – certain creatures such as starfish or sponges lack a perceptual apparatus and yet have extravagant forms and colors.10 Portmann thus highlights the importance of unaddressed appearance, of sheer visual appearance even without the possibility of reciprocity that challenges the polarity of seer and seen.11 These unaddressed animal appearances that can exist without a perceiver have their place among the non-spectatorial approaches explored in this essay.

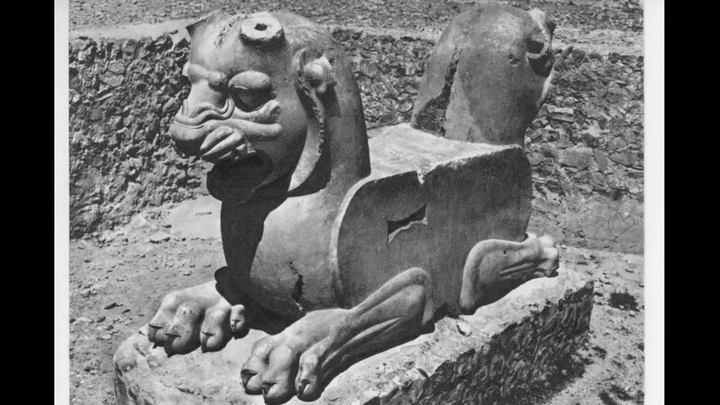

Artists are also redefining nonhuman subjectivities, by exploring the sentience of stones, metals, plants or machines. Take Verena Walzi’s installation Dialectic Libido (2015), a slide projection showing ancient ruins accompanied by a spoken text evoking speculative realist thought: “how does it feel to be a stone … nothing stranger, than those humans, who try to interpret us. We have been there long before and we will be there long after … To know about the thing itself, may be desirable, but it can't be reached.” The work conjures up a world that is indifferent to humans, evolving at its own pace and rhythm and characterized by unaddressed appearances that exist without needing to be seen.

Meanwhile Raphael Hefti’s Underlay Push Sticks (2016) (working title) is a set of massive steel bars that were exposed to the daily temperature changes of an industrial oven for hardening metals over the course of five years. This condition of a constant temperature change from 20°C to 1200°C and back to 20°C has the effect of speeding up the ageing process, simulating an acceleration in time of about 1000 years in outside weather conditions. The work addresses nonhuman timescales, as implied by Meillassoux’s notion of ancestrality: it makes these timescales perceptible and more accessible to human understanding.

In Jean-Luc Bichaud’s Carcasses (2017), living branches have been grafted onto the legs of Louis XV armchair frames. Here, the forced association of living and dead wood, of a functional and a non-functional object, of a man-made and a natural object, demonstrates object-to-object interactions taking place on multiple levels, all in the absence of humans.

My last example is not about an artwork, but about the emergence of digital images, which as Trevor Paglen points out, prioritize machine-readability: an image taken on a phone, for instance, needs a secondary application to be visible to the human eye.12 These images reverse the relation between seer and seen, for the question is no longer whether we are looking into the cameras but whether the cameras are looking at us. This reversal recalls Lacan, who referring to a sardine can floating at sea, insisted that he did not master it, but that it grasped and solicited him.

That said, the images produced by the machinic gaze of surveillance cameras and the like are usually unseen and ungrasped by us, but nonetheless call for a new perspective, if the paradigm they represent is to be understood. As Paglen writes: “If we want to understand the invisible world of machine-machine visual culture, we need to unlearn how to see like humans. We need to learn how to see a parallel universe composed of activations, key-points, eigenfaces, feature transforms, classifiers, training sets, and the like. But it’s not just as simple as learning a different vocabulary. Formal concepts contain epistemological assumptions, which in turn have ethical consequences. The theoretical concepts we use to analyze visual culture are profoundly misleading when applied to the machinic landscape, producing distortions, vast blind spots, and wild misinterpretations.”13

If we have difficulty in accessing nonhuman subjectivity, it may well be because humans are as yet unable to formulate the new theoretical concepts that would give nonhuman entities the place that is their due. Even just to speak of defining nonhuman agency and sentience is a typically human, anthropocentric enterprise, for as Tim Ingold suggests, agency as we know it may not even exist. We are starting to formulate answers to these questions, but there is still a long way to go.

An initial version of this essay was presented at “Nonhuman Agents in Art, Culture and Theory”, an interdisciplinary conference organized by Art Laboratory Berlin on 24-26 November 2017.

[1] Julian Jason Haladyn, 'On “The Creative Act”', toutfait.com, April 2015, http://www.toutfait.com/on-the-creative-act/

[2] Suhail Malik, 'Reason to Destroy Contemporary Art', in: C. Cox, J. Jaskey, S. Malik (eds.), Realism Materialism Art, Sternberg Press, 2015, p. 186.

[3] Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude, trans. Ray Brassier, Continuum, 2008, p. 5.

[4] Ibid., p. 10.

[5] Steven Shaviro, 'Non-Correlational Thought', in: C. Cox, J. Jaskey, S. Malik (eds.), Realism Materialism Art, Sternberg Press, 2015, p. 197.

[6] Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, or What It's Like to Be a Thing, University of Minnesota Press, 2012, pp. 73–74.

[7] Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, Duke University Press, 2007, p. 33.

[8] Tim Ingold, 'Materials against materiality', Archaeological Dialogues, 2007, http://home.zcu.cz/~dsosna/SASCI-papers/Ingold%202007-materiality.pdf

[9] Tim Ingold, 'Les matériaux de la vie', Multitudes, Winter 2016.

[10] 'Relire Adolf Portmann pour voir les animaux autrement', The Conversation, February 2017, https://theconversation.com/relire-adolf-portmann-pour-voir-les-animaux-autrement-71251

[11] Véronique Fóti, Tracing Expression in Merleau-Ponty, Northwestern University Press, 2013, p. 88.

[12] Trevor Paglen, ‘Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You)’, The New Inquiry, December 2016, https://thenewinquiry.com/invisible-images-your-pictures-are-looking-at-you/

[13] Ibid.