Self-reflection generally makes things difficult for flatbed scanners. Visual confusion arises if there is something transparent or even a mirror on the glass surface under which the device’s illumination and scanning unit moves. That is because the light that the scanner emits, which is reflected by the object and which the scanner's moving sensor tries to capture line by line, dazzles the machine while it is systematically measuring the object. Navel-gazing simply does not succeed with that kind of play of light.

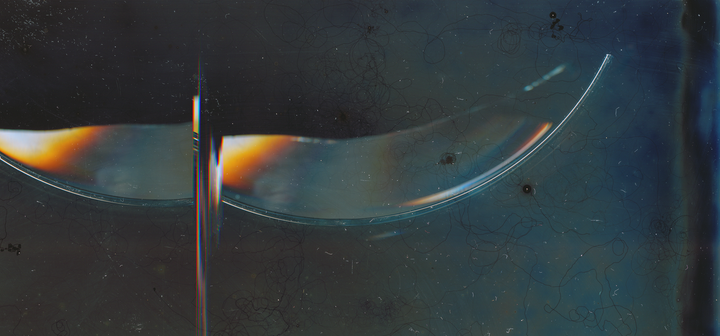

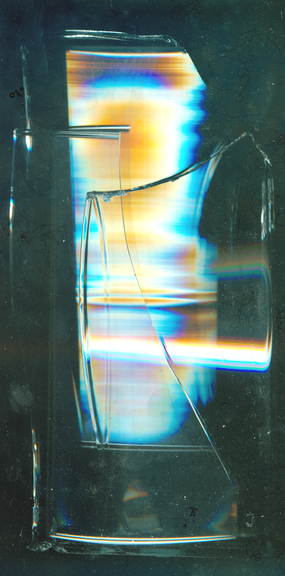

Mladen Bizumic's research and eponymous installation, MoMA's Baby (2019), take as the point of departure this disruption of self-perception - the moment when the process of digitalization fails due to the characteristics of the analogue original. Using his commercially available HP Scanjet G4050 scanner, which is however rather outdated and creates imprecise images due to an infestation of mould, the artist has produced a series of works that are lens- based and can thus be classed as photographic. ALBUM (Ikea Cylinder Scan Day), ALBUM (Ikea Cylinder Scan Night) and ALBUM (Chipped Glass Vase) are three large-format photographic prints that display a high degree of abstractionon, although on closer inspection the glass objects Bizumic scanned and moved during the digitization process are at the same time still recognizable. Like the scanner that no longer functions properly, the objects used are also damaged. The glass of the originally cylindrical vases, iconic Ikea home accessories, is broken. The images depict shards of glass positioned next to or on top of each other, with their reflection of the scanner's light manifested as an iridescent glow and a prismatic colour gradient on the photographic paper. While ALBUM (Ikea Cylinder Scan Day) focuses on the interplay of light and backlight and the effect resulting from this interplay on the scanned objects, ALBUM (Ikea Cylinder Scan Night) shows the scanner's glass plate in detail. Here dust is literally depicted and fungal spores, barely perceptible to the naked eye, ripple over the surface of the technological device. Scanning becomes a microscopic process, with the digital image as the outcome of this process.

As the titles of the works suggest, Mladen Bizumic shot one of the two works in daylight, the other by night. Unlike the scanning process for flat documents such as photographs, the lid of the scanner cannot be completely closed when recording three-dimensional objects, which means that light penetrates into the housing of the apparatus. This additional incident light is just as constitutive for the result of the imaging procedure developed by Bizumic as the technological device's obsolescence. The intensity of the incident light depends for its part on the time of day when the artist works in his studio.

Bizumic's workplace also appears as part of the installation because it is one of the conditions determining the creation of MoMA's Baby. Three photographs show various views of the artist's studio: views looking into the rooms where the scans of the ALBUM series of works were created and where all the instruments and tools that the artist used to create this series are to be found too. The studio photographs, for example, include a model of the entire installation, as well as broken glass, test prints and cameras, along with older works by the artist that contributed to developing the final exhibition situation. What becomes visible in the case of the scanned pieces of glass, namely the scanner's apparatus and the technological system that is generally concealed behind the work, manifests itself in the work STUDIO (A Conversation with Joan Levin Kirsch) as an art-historically charged gaze into the studio and at the same time as a self-reflective moment in photographic production.

The tag-line of these works A Conversation with Joan Levin Kirsch refers to another visual level in the photographs, underpinned by research conducted by Bizumic. The studio photos include excerpts from an interview the artist conducted with Russell Kirsch's spouse. Russell Kirsch, a former engineer at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards, developed the first digital image scanner in 1957, thus laying the groundwork for other technologies such as satellite imagery, the omnipresent barcode, and, last but not least, digital photography. Reproductions of the first scan in the history of technology are also integrated into the workspace images. It is a digitized photo of Walden Kirsch, Joan and Russell’s son, who was only a few months old at the time.

It was due to her visual expertise that art historian Joan Levin Kirsch, who worked inter alia at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., played such an important role in her husband Russel Kirsch’s technological developments. Taking questions of style as their starting point and drawing on the work of Richard Diebenkorn, an American painter close to Abstract Expressionism, the couple jointly developed compositional rules that are omnipresent in algorithmic thinking today. "Russell went to various museums and said, 'Look what you can do with algorithms'. But the museums weren't interested. He was way ahead of his time," says Joan Levin Kirsch, who is now active as an artist and seeks in her collaboration with her husband to embed technology within art and culture: "Today we know that many artists use algorithms for their images. There is no question that computers have influenced people's tastes and preferences. Russell is not responsible for this. It just happened. Whether you like it or not, it's definitely important as an art phenomenon. What a revolution it was when oil paint was developed! Changes to the material change art."1

With MoMA's Baby, Mladen Bizumic continues his (visual) research on the conditions shaping photography, on the photographic in times of mutual interpenetration of the digital and analogue, as illustrated by Kodak's corporate history in his book Photo Boom Photo Bust, published in 2018. "Like air and water, the digital will only be noticed by its absence and not by its presence," Nicholas Negroponte, professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, noted already more than 20 years ago: "Computers as we know them today will a) be boring, and b) disappear into things that are first and foremost something else: smart nails, self-cleaning shirts, driverless cars, therapeutic Barbie dolls [...] Computers will be a sweeping yet invisible part of our everyday lives: We'll live in them, wear them, even eat them. [...] Face it - the Digital Revolution is over."2

With MoMA's Baby, Bizumic begins with the post-digital, with that state in analogue-digital space in which interaction and the mix of manifestations are in the foreground. The way in which he repeatedly falls back on historical moments to direct his gaze to the present suggests that for Bizumic the driving force is self-reflection, which causes such problems for flatbed scanners.

Translated by Helen Ferguson

[1] From Mladen Bizumic's unpublished conversation with Joan Levin Kirsch for the project MoMA's Baby (2019).

[2] Nicholas Negroponte, Beyond Digital, in: Wired, January 12, 1998; http://www.wired.com/1998/12/negroponte-55.

MoMA's Baby is part of the exhibition Uncanny Values - Artificial Intelligence & You, MAK Vienna, 29th May to 6th October 2019; http://www.viennabiennale.org/