Issue 3/2019 - Freedom Africa

Changing Imbalances

Anette Baldauf in Conversation with Elizabeth W. Giorgis

When this issue was first prepared, one of the original title ideas was “Out of Africa,” pointing (metaphorically) towards new frameworks of thinking about the continent beyond well-known discursive confines. On a literal level, “Out of Africa” refers to the eponymous memoir written by Karen Blixen in which the author looks back upon her years spent on a coffee plantation in colonial Kenya in the 1920s. In 1985, Meryl Streep and Robert Redford introduced this narrative to a mass audience, where the epic film drama fostered what the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o called “the greatest myth at the heart of the Western bourgeois civilization”1. With its captivating imagery of nature, wildlife and – following this colonial chain of equivalency – those rendered as natives, the portrait of Kenya reproduces a white savior trope that is devoid of any references to colonial violence. Taking this as a kind of (biased) background for the following encounter, the question was how to get out of the “Out of Africa” frame. How to start a conversation in which “Africa” is not first and foremost the narcissistic projection of a female bourgeois European subject?

Anette Baldauf: Can we start our conversation with talking about your most recent publication, “Modernist Art in Ethiopia” (2019)? It is an incisive account of twentieth and twenty-first century art in Ethiopia from the perspective of visual culture, literary and performance studies.2 The books assembles a wide range of cultural artifacts and practices, including for example church paintings, fashion items and healing ceremonies, and relates them to local cultural and political currents as well as larger global movements registered under the rubric of modernism. It seems to me a negotiation of two dominant approaches, one framed by the colonial gaze projected onto Ethiopia by the West, and one unfolding upon Ethiopia’s claim to exceptionalism rooted in the defeat of the Italian colonial submission in the legendary battle of Adwa in 1896. Can you talk about the relationship between these two narratives, and how your book positions them?

Elizabeth W. Giorgis: I argue that it is impossible to fully appreciate the conditions of African modernism and by extension Ethiopian modernism in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries without considering the political and cultural implications of colonialism and the politics of decolonization. But how the central issues of coloniality were translated, transformed, and adapted in the making of Ethiopian modernism is paradoxical. Scholars and artists of non-colonized Ethiopia have unapologetically expressed deeply ingrained feelings of exclusivity from the colonial encounter. They continue to abstract any sense of commonality with the colonial experience. The silence and void around the historical, cultural, and political configuration of the imperial-colonial matrix of power and its condition in the Ethiopian intellectual space is still deafening.

Developmentalist projects are more important, and the ideological orientation of scholars and artists has submitted to new forms of donor-oriented ideological and discursive themes, discounting the urgent interventions of colonial studies and its relationship to Ethiopian aesthetic imaginings. Such studies have generally not been acknowledged in Ethiopian academic and artistic inquiry. And the larger contexts of African or non-Western modernism have rarely been deciphered. This lack of academic and artistic inquiry has in turn contributed to the sidelining of Ethiopian artists from the international art platforms where in the past two decades artists from Africa and the wider African diaspora have participated. Today the well-known African curators like the late Okwui Enwezor are interested in critical artists, who can engage the different forms of new colonialities.

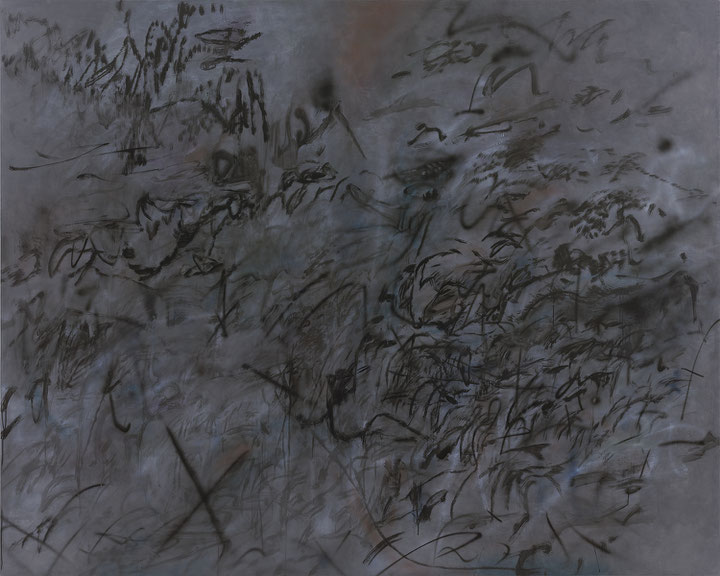

Baldauf: In the West, most cultural artifacts addressing “Africa” are in fact expressions of people who do not live on the continent. My first, and maybe too obvious, association here is the discussion around Ryan Coogler’s “Black Panther.” The Kenyan journalist Larry Madowo called it an African „utopia of sorts;“ as an African, he stressed, he did not feel represented since there was only one African artists (Babes Wodumo) involved in the major production.3 This disjuncture also marks many constellations in the art world: Exhibitions framed around “African” art often show the work of artists living in the diaspora or visitors from the West. It seems to me that your work as a writer, curator and educator is a consolidated effort to challenge this unevenness: The Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes in Addis that you organized in spring 2019 addressed first and foremost artists from the African continent, and at the Gebre Kristos Desta Center you make space for local art – last year, for example the incredible show of Bekele Mekonnen explored the associative powers of the textile patterns referencing the terror of both, the regime of the military and that of the orthodox church, and in consequence also the political landscape of censorship – and try to foster its dialogue with art produced in the diaspora. The Addis Show of Julie Mehretu was a telling example of such an orientation. What are some of the challenges you face in supporting Ethiopian art and artists; and, maybe more appropriately to the point of this issue, how do you frame the relationship between so-called African and Ethiopian art?

Giorgis: Although one can create a clear connection between traditional African art and traditional Ethiopian art, the study of Ethiopian art, which is really Orthodox Christian paintings, has historically focused on its relationship to Byzantium art with no focus on its African connection. The assumption is that Ethiopia was one of the few early Christian kingdoms. And Ethiopia’s Christian empire had nothing to do with the rest of the continent. But some of the symbolism that constitutes Orthodox Christian art does not constitute a Byzantium repertoire and can be easily related to West African symbols and iconographies. But the scholarship of Ethiopian Christian art, which is dominated by European writers, completely discounts that. The irony is that these same writers refer to Ethiopia’s Christian art as art that came from Byzantium but did not have the same finesse as Byzantine art. On the one hand, they remove the art from its African context because of Ethiopia’s Christian standing. But on the other hand, they denigrate its skill since it could never compare to the fine art of Byzantium paintings.

Baldauf: In her book, “Lose Your Mother,” the US-American scholar Saidiya Hartman recalls her research trip to Ghana, where she was hoping to find material to counter the “non-history” of slavery prevalent in the archives of US-America. In a parallel and interwoven story, she reflects on how her search to reconnect with kin and country was countered with continuous alienation; the persistent differentiation between Africans and Blacks from US, placing her, the author, inevitably as a stranger to the continent. In one of her final remarks she concludes: “In Gwolu, it finally dawned on me that those who stayed behind,” (the survivors of the slave trade) “told different stories than the children of the captives dragged across the sea.”4 And, it seems, those who stayed behind tell these stories differently depending, among others, on their particular history of colonization. How do you in your work approach and negotiate the relationship between concepts like Ethiopian, African, black and African-American?

Giorgis: This relationship is kind of ambiguous. My experience is different from many Ethiopians. I left Ethiopia when I was young and went to an all black school (historically black college) – Morgan State University – in Baltimore, Maryland. You can say my formation was related to African American causes. I have, nevertheless, talked to several non-African American scholars in the US who are ambivalent in connecting their causes to African American causes. They refer to themselves as Caribbean scholars if they are from that area or African scholars if they are from Africa. They say their experiences of marginality are totally different from African Americans and have to be articulated differently than African American problems.

My nephews and nieces who were born and raised in the US consider themselves Ethiopian Americans who are black people in America and have nothing to do with the African American experience. The Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, for example, refers to this in her book “Americanah” insisting that she was a black person in America and not African American.5 So this idea of blackness does not have a universal meaning. Each group has its own interpretation although all agree of the marginalities they encounter because they are black.

[1] Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Moving the Center. James Currey 1993, p. 135.

[2] Elizabeth Giorgis, Modernist Art in Ethiopia. Ohio University Press 2019.

[3] Larry Madowo and Karen Attiah, ‘Black Panther’: Why the relationship between Africans and black Americans is so messed up, in: The Washington Post, February 16 2018; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2018/02/16/black-panther-why-the-relationship-between-africans-and-african-americans-is-so-messed-up/

[4] Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. Farrar, Straus & Giroux 2005.

[5] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah. Alfred A. Knopf 2013.

Elizabeth W. Giorgis is professor of theory and criticism at College of Performing and Visual Art, and Director of the Modern Art Museum Gebre Kristos Desta Center at Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. She previously served as Director of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies and Dean of the College of Performing and Visual Art at Addis Ababa University. She is the editor and author of several publications; most recently she published “Modernist Art in Ethiopia” in the New African History series at Ohio University Press (2019). She has curated innumerous exhibitions including “Julie Mehretu. The Addis Show” (2019), “Time Sensitive Activity”, an exhibition of Olafur Eliasson’s work (2015), and “The Enigma of the New and Modern” (2013).

Anette Baldauf is a sociologist and educator. Her work focuses on the intersection of art, research and pedagogy, with a special interest on the politics of space, place and land. She is professor of Methodology and Epistemology at the Academy of fine Arts Vienna, where she co-directs the PhD-in-Practice Program. Baldauf and Giorgis have been collaborating on different projects since 2014.