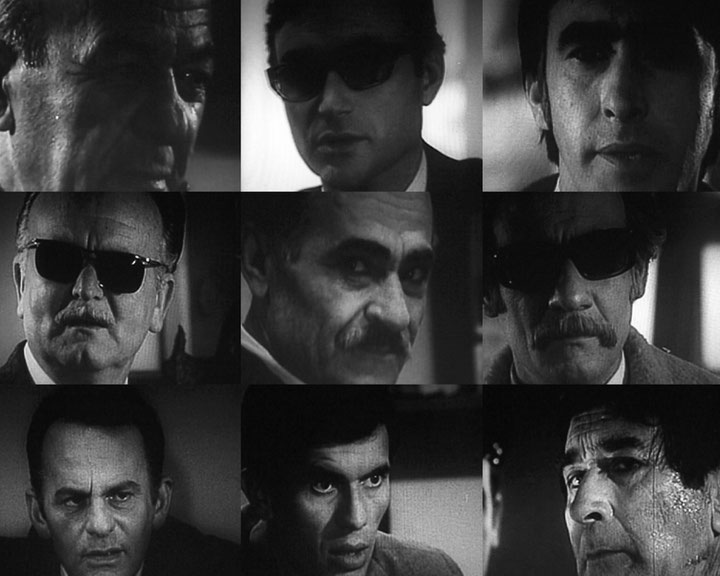

Fani Zguro’s Broken Threads (2007) juxtaposes black and white shots from an Albanian spy movie with the dark tune of a murder ballad by Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds.

In the film—Fijet që Priten (1973), which also translates as broken threads—foreign agents and their local infiltrators conspire to destabilize the new Albanian society and undermine its achievements on the socialist path.

Assembling all the scenes in the film depicting the foreign agents, Zguro produces a collage of hip looks and western airs, fur coats and dark shades, incarnating what was then publicly demonized, but privately longed for. Wedded to the dark voice of Nick Cave, the sequel evokes a recollection of hushed penchants and covert desires. Naturally, Cave’s demeanor bolsters the villains’ badass aura.

In their song “The Curse of Millhaven” (1996), Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds portray the gloomy atmosphere of a fictitious American small town, as told by Loretta, a homicidal 15-year-old girl. The song is a distant upshot of roots revival, a trend that grew global in the 60s and 70s as it instilled a particular political expression and urgency in rock songs by incorporating folk elements or gory stories into their structures. Yet, the demonic ambiance in “The Curse of Millhaven” incites more withdrawal than rebellion. And its narrative amusingly befits the communist propaganda about decrepit life and disaffection on the dark side of the capitalist moon.

In a loose adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s Demons, Jean-Luc Godard touches on what could be seen as a reversed context. In his film La Chinoise (1967), five disgruntled Parisian youngsters, distressed by the escalation of American imperialism and society’s surrender to consumerism, convene in a bourgeois apartment to bring about change by revolutionary means.

I see similarities between the revolutionary five and the imperialist spies, not only between their poseur airs and hip style (or their fetish for sunglasses), but also their zealous predilection to disrupt and overthrow. Despite their antagonist aspirations, there is an affinity between the glum setting of Fije qe Priten and “it’s small and it’s mean and it’s cold” Millhaven. Regardless of their apparent differences, the fiery Véronique (played by Anne Wiazemsky in La Chinoise), reciting from the Little Red Book, echoes the hurting Loretta enumerating her murders through Cave’s beguiling timbre. They both exude a mood of “To be on your own / With no direction home.” United in their versatility, the aforementioned juxtapositions expose en passant the revolving nature of the end of ideological eras, as well as the fallacies of their zeitgeists.

“Because the world is round it turns me on / Because the world is round …” (The Beatles, Because, 1969) … it takes blindfolded precision to slip through history’s cycles, without asking yourself Because.