Issue 3/2021 - Net section

„Can you imagine solidarity?“

In Barbara Kapusta’s oeuvre, leaking bodies and social surfaces are the protagonists of a future world inspired by techno-feminism and science fiction

Her work is “comforting”,1 one viewer commented on the screening of The Leaking Bodies – an animation by Barbara Kapusta shown as part of an online event in February 2021 on the occasion of her exhibition at Galerie Gianni Manhattan in Vienna. In the light of its images, depicting a “leaking” pipeline from which oil drips greasily onto an arid, post-apocalyptic desert landscape, encountered by a sweating (or already burning) metallic arm, the forest fires that swept southern Europe in summer 2021, sparked by the climate crisis, spring to mind – at first glance anything but comforting.

However The Leaking Bodies is not about commenting on the acute environmental crisis, but much more fundamentally about addressing and overcoming traditional conceptions of the human that are responsible for the problem in the first place: “What caused the damage?” asks a voice from this world determined by fluidity, in which the male/female narrator is at the same time an I and a we, a multitude: “We travel in contaminated lands. Yellow, dusty regions, orange shadows, and dry skies. I feel like a global fluid. You penetrate all boundaries”.

In the text accompanying the animated images, which is unusually poetic for a political work, Kapusta opens up an associative field structured around traces of “flows” – capital flows, transportation of crude oil, drinking water, but also bodily fluids – that establishes direct links between themes of migration, exploitation of resources, the narrative of the desert as an inhospitable place, water privatisation, human penetration into the remotest areas, and even Covid-19: “A slimy, slippery mixture on dry, yellow grass and corroding iron. Slowly contaminating every part and cell of our wet and fragile existence”.

Combining language and text with objects, sculptural and animated bodies, letters with numbers, hard and soft materials is a hallmark of the artist’s work, which addresses the materiality and linguistic constitution of bodies in installations, animations and lecture performances.

This is supplemented in The Leaking Bodies, the latest animation by the 2021 Otto Mauer Prize winner, by an understanding of corporeality as a permeable membrane because, in the artist’s view, we all leak: sweat, blood, urine, tears, but also hormones, traces of antidepressants or Covid-19 mutations that can be detected in sewage.

“What caused the damage?” the voice enquires again and the answer includes all of us: “The loose ends of our dripping culture. Our leakiness”.

The meanings of the word “leaks” leverage dual thought processes: after all, leaks do not simply have environmentally destructive potential, but also serve the public interest when leaked data exposes the machinations of governments, corporations, etc. It had already become apparent in her two earlier works Empathic Creatures (2018) and Dangerous Bodies (2019) how the artist entangles the seemingly pristine digital dimension in contradictory and ambivalent narratives by transforming smooth, shiny surfaces into sticky, haptic silhouettes and figures that defy identification: “Bodies had been modes of perceiving conventions and proportions for so long”, asserts the Dangerous Bodies collection of texts that accompanies the work and continues: “The new bodies wanted to be superfluous, unnecessary, unfit”.

In her exhibitions, her reflections on a better life in a community supported by empathy and solidarity can often be seen in the form of acrylic glass speech bubbles set alongside object-like prostheses and body fragments: “Can you imagine solidarity, solidarity with the other ones, a group, a society, a mass of people and their identities?” enquired the exhibition The Giant (2018) at Galerie Gianni Manhattan, addressing viewers directly.

In the Dangerous Bodies animation, accompanied by the dystopian-futuristic sound of young Viennese musician Rana Faharani, encounters unfold between corporeal creatures able to change physical state, open up fluidly to their surroundings, and then to view the world from afar again as self-contained entities. Their bodies seem battered and vulnerable, evoking not only aliens but also refugees in camps across Europe: “We linger and inhabit shelters […] Our bodies are hard and real, we breathe and we weep”.

People however apparently do not spark solidarity in Europe by breathing and weeping. How would the bodies have to be constituted, the artist asks, how many could there be for people to still declare solidarity, and what happens if they – like the (minority) bodies in Dangerous Bodies – afford scarcely any potential for identification? In raising these questions, Barbara Kapusta strikes at the heart of the inflammatory anti-migration narratives that colour the current political situation in Europe under the influence of centre-right governments, as she endeavours to develop a utopia based on techno-feminist theories in which bodies can flourish with equal rights, irrespective of their origin, gender, economic status, education, etc.

Her blueprints, which she views not as utopian but as critical approaches to current circumstances, draw inspiration from Donna Haraway’s cyber-feminist theories, the post-apocalyptic short stories of American science fiction author Octavia E. Butler, Paul B. Preciado’s story of his transition, as well as the radical reflections on overcoming family structures formulated by Sophie Lewis in 2019 in Full Surrogacy Now. Feminism Against Family. Kapusta builds on the emancipatory promises that these feminist approaches (some 30 years old) associate with biotechnological progress, while also taking up their critique of the racialised and sexualised charge imbuing technology.

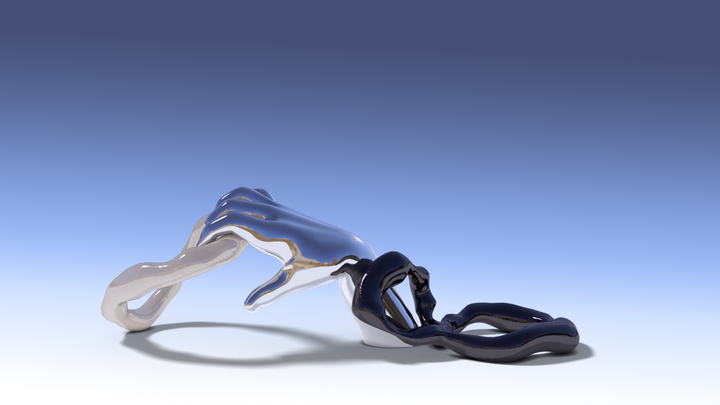

Empathic Creatures, an animation that brings together object-like elements from earlier works – a hand, an “8” and an “O” –, is (also) about technical imperfection. In the Enjoy (2021) exhibition of works from mumok’s collection, the material representatives of these “figures” are made of smooth, fragile porcelain. In the animation, their shiny metallic surfaces and curves touch gently, resting side by side and interlocking. At some point, the hand clenches into a fist, the “8” tenses up: “When we feel, we feel so deeply. We rack and shatter into pieces and parts, this is the vulnerability of our society of empathy”.

At some point the structure fragments into a thousand pieces, pushing the viewer to realise that empathy does not exist “naturally” in a society, but must be worked on or – as Barbara Kapusta suggests – trained and practiced. “The end of the world is so easy to picture, much easier than its continuity”, the voiceover asserts. Kapusta’s images point to a possible aftermath and encourage the development of concepts and ideas concerning solidarity-oriented, inclusive, transhuman, more environmentally sustainable future communities. That comment from a viewer proves to be right: that is very comforting nowadays.

Bibliography:

Octavia E. Butler, “Speech Sounds”, in: Bloodchild and other Stories, Seven Stories Press, 1996/2005.

Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet. University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Sophie Lewis, “Amniotechnics”, in: Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now, Verso Books, 2019.

Elisabeth Povinelli. Geontologies. A Requiem to Late Liberalism, Duke University Press, 2016.

Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie. Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, The Feminist Press, 2013.

Sylvia Wynter. On Being Human as Praxis, Duke University Press, 2014.

Translated by Helen Ferguson