AIR SPACE

Welcome Home! The slogan of the travel platform suggests being able to leave without having to arrive. Navigating without friction, without otherness, without uncertainty. It’s January, 2021. A wooden cabin nestled deep in the snowy Nordic mountains, set by the water of an idyllic narrow fjord. She arrives late at night, after a daylong journey by plane, boat, bus, and last but not least, on foot—trudging through knee-high snow. The small but perfectly formed structure, designed by young architects and constructed from local wood, makes the most of its hillside location. It represents a new generation of cabins with modern architectural designs featuring floor-to-ceiling windows that allow the framed views and nature to take center stage.

She enters the access code of the smart lock and checks herself in. It works friction-free. Convenient in its function and minimalist in feel, the cabin has lots to offer; ever more so, in the current pandemic, when connecting to nature becomes more important than ever. The space is clean and bright and modern. She finds it pleasing. Yet would she be able to work, to contemplate? She once read that the existence of resistance defines the place of intelligence in creative production. Without internal tension, there would be a fluid rush to a straightaway mark—nothing that could be called process, development, and fulfillment. As in art, isn’t it so in life: resistance prompts us to think? Has she arrived in a place precisely without the qualities that current critical discourses have emphasized as particularly significant? Don’t we need action and thinking that do not fit within dominant capitalist cultures? New practices of imagination, resistance, revolt, repair, and mourning and living and dying well?

HERSTORY

She is what they call an independent researcher with no institutional affiliation. She has an adjunct gig at a university, but it is in the visual arts department. Her academic colleagues find her vaguely disreputable. Artistic practice as a creative and critical form of human engagement that can be conceptualized as research? For them it is defined by indeterminancy—constantly in flux, lacking coherence and identity. On her reading, however, it is a potent pedagogical method of resistance within a university landscape.

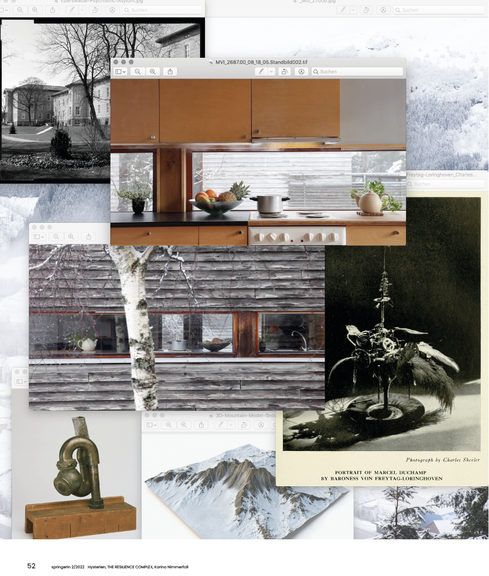

She came to make some progress on her script for a new work. A project that explores the relationship of subjectivity, psycho-social health, and creative work in our crises-shaped world. Her plan was to develop a narrative based on a past that is remembered not as it was or as it could have been, but as a virtual history. An experiment where the historical past is not a discrete moment in time, but rather an actively engaged part of the present moment. She knows that her present has a foot in the past and another in the future. Hence, she seeks to discover and make connections between events, characters, and objects that join together in memory. The protagonist: a barely recognized artist who has long been shelved in cultural history under the rubric of eccentricity and madness. A key figure of New York’s Dada scene. From today’s view, however, her art is far from being evidence of madness, craziness, or marginality. Her dislocation of conventional femininity intersects with post-modern notions of radicality. Madness was the chosen state of her art. She was New York’s first punk persona sixty years before their time. A pioneer of gender play, acting out in the contemporary art world as though she were a very distant great-aunt of feminist performance art. She can’t remember who told her first. Sometimes it feels like she had always known about her. She was one of her contemporaries. She was her medium. A revenant, walking from one story into another.

CREATIVE LABOR ANXIETY

Can the past serve as a hiding place from the present? She is writing not only to tell. She is writing to discover. Fragments of lives and dramas that she only has glimpses of, but that serve as testimony to the fleeting presence of women as subjects across a vast landscape of the past. Yet, why is it so difficult to switch between subjective experiences and objective findings? The signs are everywhere, in a place, in a book, in a moment in time. They share the same birthday, one-hundred years apart. She wants to understand how she and her were connected. Create relations of the past, present, and future, as an experience of non-serial immediacy. Following this lead, wouldn’t that also mean to turn around and rupture the continuum of homogeneous empty time, that is—as it was once stated—rooted in capitalism?

What prompted her endeavor was concern about the state of the world. She was seeing the progress that one thought had been made, being reversed. We were told that we live in a time of great promise. That we have evolved economic and social systems that tap human creativity and make use of it as never before. Human creativity as the ultimate economic resource. Capitalism, however, seems to has had a complex effect on our understanding of 'equality'. Did the desires of the twentieth-century women's liberation achieve their fulfilment in the shopper's paradise? She was confounded by the neoliberal credo of self-optimization, meritocracy, and willingness. Does being an artist necessitate a certain kind of withdrawal from the world, and from the circuits of capitalism, in so far as this is possible? The contemporary art world hardly seems to indicate that this is desirable. Remember the characterless (but in return equally flexible in work, private life, and morals) human being who can bend like a tree in the wind, but then returns to their original shape? Isn’t the artist the new face of flexible labor for many?

Perhaps, for the sake of honesty, it should be added here that her research is not only for her work. She has been living what feels like a double life. All artists do for sure, but the female artist has an implicit double-job to undertake. Consequently, she is hoping for a side effect that would be useful to her personally as well—to find suggestions on how to remedy her own state of exhaustion, which is already quite manifest. Too much work, with little security and concrete future perspectives in academia—the general and widespread process of precarization, with its paradox, that one is promised freedom while also being subjugated to this normalization of risk and uncertainty. Dimensions of creative labor anxiety, a spiral into despair?

ARTIST / WARRIOR / WOMAN

Where have all the interesting women gone? She wakes up at seven o’ clock, washes her face and goes straight to her desk. Morning fog is lifting from the fjord below. She sits in a chair for hours, connected to a laptop, command and information flowing through her body. A hybrid creature, composed of organism and machine, seeking to identify ‘a world’ of female subjects that capitalism had to destroy in order to proceed: the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the Obeah woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired slaves to revolt. She turns her eyes towards the door, and watches it open. A woman enters the room. As always, she is late, working on her costume. She is wearing a trailing blue-green dress and a peacock fan. One side of her face is decorated with a canceled postage stamp. Her lips are painted black, her face powder is yellow. She wears the top of a coal scuttle for a hat, strapped under her chin like a helmet. Two mustard spoons at the side give the effect of feathers. The year is 1921. The setting: an avant-garde literary magazine office in New York, its walls painted black. The principal performer: an artist in her late forties, known in Greenwich Village as the Baroness.

Was she wild and untethered, urging toward forever new and unexpected forms? Isn’t it surprising and telling at once that this interpretation is orientated toward the unconscious and the animal-like? It has been said that we polish an animal mirror to look for ourselves. Her style is aggressive and excessive, yet is there really a disorder when a person has created a state of consciousness, which is madness, and adjusts (designs and executes) every form and aspect of her life to fit this state? Aren’t artists who take up the matter, the material world, the mess of things, reminding us that one never thinks in a vacuum, and one never can? Thus, isn’t the grotesqueness reflecting the trauma created by the Great War something that had to be countered by assaults on current belief systems? So she shaves her head. Next she lacquers it a high vermillion. Then she steals the crêpe from the door of a house of mourning and makes a dress out of it.

CLOSE TO THE EDGE

Disturbance disrupts: patterns, assumptions, habits, business as usual, normative modes of body and mind. It’s February, 2021. Early in the afternoon. There is something uneasy in the air, some unnatural stillness, some tension. The weather is expected to take a dramatic turn, bringing unusually warm air from the Atlantic. What it means is that a wind will begin to blow, a hot wind, dropping off most of its moisture when it descends the mountains, resulting in heavy snowfall. She knows it because she feels it. The wind shows us how close to the edge we are. It brings the nerves to the flash point.

She had suffered from migraines since childhood and has long been curious about her own aching head. Three, four, sometimes five times a month, she spends the day in bed, insensible to the world around her. “What is the matter with you?” “I am not sick, I am in pain”. She is not searching for meaning, because it doesn’t mean anything. When the pain comes, she concentrates only on that. Throbbing, flickering, quivering, pulsing, beating: temporal dimension. She had to relax her brain instead of flex it. When the pain recedes, everything goes with it, all hidden resentments, all the vain anxieties. There is a pleasant convalescent euphoria. The migraine has acted as a circuit breaker, and the fuses have emerged intact. There seems to be, however, another player in the matrix. As a study once suggested, torture and creativity appear related: the rewired network might lead to the recontextualization of the situation in which the confused and conflicted subject finds itself. A little pain as a good thing?

HAUNTING LIKE A GHOST

Are we living in hysterical times? Traveling from the interior of our nervous systems to global media networks. It has been said that the hysteric, who was a well-represented poster child in European artistic and scientific studies at the fin de siècle, is celebrating a surprisingly popular comeback. Hysteria today, however, seems more contagious than in the past. Its cultural narrative spread by stories circulating through our networked realities—multiplying rapidly and uncontrollably. Yet, doesn’t nearly every time when the word hysteria is used now, the writer points out that the root comes from the Greek ‘womb?’ Its origin as a purely female problem connected to the reproductive organs serves to warn readers that the word itself is an ancient bias against women, haunting like a ghost. But isn’t its history far more complicated than misogyny?

To imagine the future, we should perhaps start from the more or less recent past. She had herself suffered a hysterical fit. Child-free and now in her fifties, she was living a life of her own. Unable to escape the icy grip of poverty, she was always on the move. As a woman, she had no country and wanted no country. Her country was the whole world. Always compelled to operate in a frenzy of networking and self-promotion amidst an almost total lack of remuneration, stability, and certainty. She had the urge to become cynical and the desire to withdraw completely—someone who prefers not to (work, have kids, keep capitalism rolling). But aren’t there always other ways of living, real or imaginary?

It's December 1924. The location: Potsdam. She reports a robbery, a disastrous event. It intensifies her sense of anxiety and crisis. She fears bed, for a specter shape enters her—there it has leisure to torture—tweek—pommel her—weaken her heart—pounding on it. The desperate crisis, however, prompts her into action. She sits down to compose the preface of a projected book. As a citizen of terror, a contemporary without a country, her hope is that a country will inherit her life, offering in return peace and decency and time. Two months later, so it is recorded, she breaks down in the streets and is admitted to a shelter and working house. The physical work, however, leaves her intellectually empty. Since they can’t further carry the personal and economic burden, she is dismissed. Shortly after, she is writing from a psychiatric asylum set in a nature oasis in a town just northwest of Berlin. She says she is sure to not be one tick insane—but only poor and déplacé. Art is her world and she needs her freedom. Her culture is where the artist is. The artist is always ahead. She is in the wrong place. One story leads to another story. One story becomes another story, and many stories are somehow the same story.

POWER POSE

Her resources are exhausted, her batteries are empty—wouldn’t it be perfectly okay to unpack the charger now and connect to the system? Or should she rather revamp her homepage? Expand her network, make herself indispensable? They all say that the world is changing at a dizzy¬ing pace and that, if we are not to risk ruin or death (for them it comes to the same thing), we must adapt to this change or, in the world as it is, be but a mere shadow of ourselves. Seen this way it is perhaps of little surprise that since the 1970s the word ‘resilience’ has become the figure of hope for entrepreneurs, policy makers, and environmentalists alike. Described as the capacity of a system itself to change in periods of intense external perturbation as a mode of persistence, it is defined in relationship to crisis and states of exception. They say that it prepares us for a present that is uncertain and inscrutable, hence in principle threatening, while giving us the means to cope. Resilience is not just a buzzword, but a key concept of the 21st century: a transformative paradigm

that propagates the flexible adaptability of subjects and systems to our crisis-shaped environment.

It has, however, a peculiar logic. It is not about a future that is better, but rather about an ecology that can absorb constant shocks while maintaining its functionality. Isn’t it in this sense a state of permanent management without ideas of progress, change, or improvement? Be mindful, reflexive, sensitive—yet not subversive. Fight only against something that can be changed, or only as long as it can be changed. Remember Wonder Woman? Strike a power pose, instead of arguing. Or let us change. But change what, in fact?

THE THIRD WINDOW

Tracking down and marketing unrecognized assets, in this case: the house and the living experience. Depending on one's perspective, this can be understood as both a threat and an opportunity. She is setting the scene. For a spacious and inviting look, she makes sure that the interior is clean and free of clutter. She opens the blinds and turns on the lights to brighten the space. Since it had been said that guests love to stay in spaces with ‘character’, she calls attention to details, showing them off. She sets up the camera in landscape format, since vertical photos in search results won’t showcase the space as well. But what is an edge and what is a center? Where does the image end and the frame begin?

Consider a window. Is it simply a void traversed by a line of sight? No. In any case, the question would remain: what line of sight—and whose? As a transitional object it has two senses, two orientations: from inside to outside, and from outside to inside. The window is communication. A gateway that opens up and allows passage to some place beyond. Imagine the house is a frame for a view. Then the view enters the house—convoluting the relation between inside and outside, imaginary and real, immediate and mediated, connection and separation. Snow falls slightly. Steam builds up. The weather changes. Now think of the window as a lens and the house itself as a camera pointed towards nature. Wouldn’t it provide us with one more flat image? It has been said that knowledge falls into a trap when it makes representations of space the basis for the study of 'life'. No matter what one uses to photograph an object, the image remains a grainy approximation. Like the translation of human life into columns and rows. Hence can the body, with its capacity for action, and its various energies, be said to create space? She places herself into the clinical construct of the living surface. Her body is fragmented, framed not only by the camera but by the house itself. Enclosed by a space whose limits are defined by a gaze. The strategy of physical separation and visual connection, of framing, is enhancing the stage-like effect. Planes and axes, duplication and reflection, repetition and differentiation. She once read that mirrors appear to be openings, and openings can be mistaken for mirrors. She sees nothing. She is an attachment to a wall that is no longer simply there. Tracing the shift from the spatialized image of the Creative Suite to the immaterializing image of the Creative Cloud: from apartment to cloud. The house is in the air. There is no front, no back, no side to the house. The house can be in any place. The house is immaterial.

READYMADE

Consider a temporary architectural display fabricated from common materials like wood and aluminum, filled with a diverse array of screens, images and texts, devoted to a radical artist, writer, or philosopher. She is trying to remember the details. It’s January 1917. An unheated loft on 14th Street. It is crowded and reeking with the strange relics that she has purloined over a period of years from the New York gutters. Old bits of ironware, automobile tires, gilded vegetables, a dozen starved dogs, celluloid paintings, ash cans, every conceivable horror, which to her tortured, yet highly sensitized perception, become objects of formal beauty.

Her best-known sculptures look like cocktails and the underside of toilets. Remember the iconoclastic sculpture that first became canonized under the name of another artist? A piece of plumbing strangely humanized in a twist of cast-iron bowels mounted on a miter box and pointing to heaven. Focusing on bodily wastes, there emerges the question if she also had a hand in the scandalous pièce de resistance that was submitted to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. Sitting on a pedestal, upside down and signed with a fake artist’s name: R. Mutt—Armut—Mutt R.—Mutter? Its provenance remains shrouded in intriguing mystery. She is not convinced that it belongs to him, although they always put his name first. Marcel, Marcel, I love you like hell, Marcel. He said she is not a futurist, she is the future. What if she had always been known as the brain behind?

EPILOGUE

She seeks to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present. To this end, she elaborates on the found image, object, and text, and favors the installation format as she does so. Artists like her are primarily interested not in producing new content, but in submitting existing content to various conditions in order to see how they behave. So it goes without saying that the best lines in this script are appropriated. Or rather, they are détourned. Because détournement is the opposite of quotation: it takes past creation as always and already held in common, allowing to combine it into a new meaningful ensemble. Let’s consider this text a hybrid space that perhaps can produce other visions of our present. Not really part of a book, not yet a new project. Isn’t there something about an unfinished piece of work, where perfection is still possible? She returns over and again to the same troublesome passages. Its meaning gets lost in a tumble of fragmented words and spliced sentences. A critic once wrote: her idea was admirable, but the form that she used to express it was too formulaic, almost procedural. Nonetheless, even though she is physically and emotionally exhausted, she is confident that she will triumph. In misery often unexpected alliances arise. Taking a step in a new direction. The artwork is not complete until she has exhausted what we mean by work. Let’s wish her the best of luck.

BASED ON WRITINGS BY:

Christian Berkes, Ellie Stathaki, Hari Kunzru, John Dewey, Richard Sennett, Donna Haraway, Graeme Sullivan, Hito Steyerl, Natalie Loveless, Stefanie Graefe, Gilles Deleuze, Marcel Proust, Timothy Barker, Henri Bergson, Mark Godfrey, Irene Gammel, Jane Heap, Robert Hughes, Margaret Anderson, Liam Gillick, Gisela Freytag von Loringhoven, Siri Hustvedt, Antoinette Burton, Walter Benjamin, Catherine Bateson, Richard Florida, Nina Power, Isabell Lorey, Angela McRobbie, Silvia Federici, SPUR, Tom Holert, Lisa Olstein, Joan Didion, Janet McCabe, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Orit Halpern, Gregory Bateson, Johanna Braun, Elaine Showalter, Alexander Galloway, Marcel Duchamp, Ulrich Beck, Virginia Woolf, Herman Melville, Amy Cuddy, Anke Stelling, Alain Badiou, Crawford S. Holling, Ulrich Bröckling, Bruce Braun and Stephanie Wakefield, Jutta Heller, Paul Virilio, Airbnb.com, Henri Lefebvre, Le Corbusier, Kenneth Frampton, Xiaowei Wang, Beatriz Colomina, Hal Foster, Alan Moore, Francis M. Naumann, Joseph Tabbi, David Joselit, Ali Dur and McKenzie Wark, William Gaddis, Charles Henry.

Supported by Nordic Artists’ Center Dale. Thanks to Arild H Eriksen.