Is it merely a historical coincidence that whenever a sort of “culture war” comes to dominate public discourse, this always overlaps with the rise of far-right movements? It did happen during Europe's interwar period, although the term “culture war” wasn't extensively used to describe the sociopolitical environment preceding the Second World War, which ultimately led to the war and the largest man-made catastrophe in human history. “Culture wars” also accompanied the rise of evangelical right-wing movements in Reagan's America during the 1980s, which aimed to undo the progressive changes in civil rights and racial justice during the late 60s and 70s. And it is happening now, again with the increasing popularity of extreme right-wing movements in Europe. Recognizing the historical correlation between “culture wars” and the ascent of extreme right-wing politics, one could reasonably suspect that the former is a manifestation of the latter, the manifestation of its very existence.

For “culture wars” could be conversely seen as the far right way of being in the political realm as an exclusionary force. This becomes apparent after one examines the diverse fronts on which far-right cultural warriors wage their battles, whether targeting LGBTQ+ communities, religious and ethnic minorities, women, refugees, or other marginalized groups. It seems evident that there is a common thread that ties all these fronts together. This thread, the exclusionary, misogynistic, xenophobic, racist political project of the far right, is driven by a nostalgic desire to reinstate white supremacy in opposition to gender, racial, ethnic, and religious diversity. Does this mean that “culture wars” are non-existent?

No, they certainly do exist, with their components being undeniably tangible. Yet, framing these various “cultural skirmishes” waged by far-right warriors solely as “cultural wars” overlooks the broader political dynamics at play. This approach fails to grasp the interconnected nature of these ostensibly disparate battles over supposedly cultural matters, thus naming the whole after one of its manifestations. Moreover, portraying the far-right war on the rights of women, LGBTQ+, refugees, Black individuals, and other marginalized groups as merely a cultural issue is problematic on another level, as such a stance reflects a troubling submission to the far right’s perspective.

Passively accepting the “cultural wars” framework without scrutiny, one contributes to the depoliticization of the neo-fascist surge by relegating it to mere cultural conservatism. This not only sanitizes the dangerous ideologies at play but also downplays the looming threat of a potential catastrophe: the resurgence of far-right power in Europe. By disguising this catastrophic possibility with euphemisms, we obscure the gravity of the situation, thereby giving a relatively ‘sweet’ name to a future catastrophe! However dangerous the “culture wars” may seem, they will always look less threatening than the actual wars, or the potential disaster of the far-right’s domination over our life. Hence, what may appear to be merely a linguistic argument around naming, is, first and foremost, a political one.

Without clear language that speaks to the complexity of the matter, there’s a risk of engaging in a phony war while missing the real one: forestalling the 2nd coming of the far right to power. The way we understand the challenge at stake predetermines our response to it. If we approach these wars, namely the “culture wars,” on their own terms without understanding the entire political project behind its far-right warriors, we are going to find ourselves dispersed into identitarian minorities of Blacks, women, refugees, LGBTQ+, taken separately one after the other. For, until we understand the political dimensions behind the “culture wars,” we remain unable to figure out how we could turn the abundance of targeted minority groups by the far right, as perceived within the context of the “culture wars,” into a political majority.

A political majority that could be materialized around a political project which encompasses all emancipatory desires in all their variations within a collective struggle against the whole system of exclusion.

An emancipatory political project, acknowledging the seriousness of the challenge posed by the rise of the far right, would staunchly oppose the politics of the liberal left. A left that has not only failed to address the issues but has actively contributed to the creation of the very environment in which the far right flourishes. It is in this neoliberal time of ours, a flat time of continuous successive instants devoid of any discernible horizon. A depoliticized time, made possible by both the abandonment of the grand political project of social justice by the liberal left and its high reliance on identity politics. It is a post-ideological left, promoting neoliberal policies while encouraging cultural controversies as a substitute for genuine debate over social and economic justice, a dystopian-left devoid of any vision for tomorrow, that lacks any sense of progress or a project for a better future. It is in this absence of any genuine aspirations for a brighter future, that one can see how a nostalgic yearning for a “better past,” despite its potential catastrophes, can come to dominate a significant portion of public sentiment.

Looking at the consistent European shift towards far-right polity over the past two decades, one could realize that this shift hasn’t been solely the result of the electoral successes of far-right parties. It also stems from mainstream parties, including the socialist left, center right, converting to and adopting policies, language, and perspectives that just a couple of decades ago, were deemed racist and xenophobic. This gradual conversion of mainstream parties to far-right ideology has significantly contributed to the rightward shift, surpassing even the impact of radical right’s electoral victories, and it has above all facilitated the rapid normalization of such ideologies.

Approaching the far-rightward trajectory of Europe in terms of speed and movement unveils a journey marked by dual velocities. Far-right parties propel forward with high velocity towards the extreme right. Meanwhile, mainstream parties lag behind, their pace may look more leisurely yet unmistakably advancing in the same direction. This could be clearly seen in many of the controversial policies and laws adopted by mainstream parties that were originally proposed and championed by far-right factions. Nowhere is this constant tailing of mainstream parties behind the extreme right ideology more evident than in the formulations and revisions of immigration laws across Europe over the past two decades, ending by the last, yet controversial law adopted by the European Union early this year, where approaches clearly drawn from far-right ideologies have influenced its content. Anti-immigrants’ rhetoric and the imposition of stringent border controls, the heavy reliance on police violence to solve political dissidence, the tendency to criminalize the difference of opinion, these authoritarian policies have become hallmarks of mainstream parties’ discourse, mirroring agendas once exclusive to the far right.

It seems that the journey toward the total dominance of the far right in Europe needs no new Hitler or Mussolini, since it is taking the shape of a gradual, yet consistent and relatively rapid conversion of the mainstream parties into far-right ideology. Isn’t this the case in France where the shift towards the extreme right has been until now, no more than the adoption of the latter’s policies and normalization of its xenophobic discourse by its apparent adversaries in the center and liberal left. Where perverted laicité has given xenophobic, racist and islamophobic policies a progressive face.

Some anti-immigrant policies on the center and the left have long managed to cloak themselves in pseudo-rational calculations based on economic durability. But then came the strikingly contrasting scenes at Poland's border that occurred within a few months' interval. In the first scene, we witness a border closed to refugees from the global south, who are left in the woods, deprived of humanitarian aid, savagely beaten by police whenever they attempt to cross, and literally abandoned to freeze and die in the cold month of December. The second scene unfolds two months later at the Poland border where a new wave of refugees arrived. However, this time, the response was a complete reversal from the previous cruelty. The scene shifted to one of unprecedented humanitarianism, embracing the refugees with a spirit of brotherhood, open borders, and hospitality. This glaring inconsistency leads us to raise the question: What caused this stark contrast between the two scenes? Conversely, what made possible this extreme difference in reaction to what appears to be the same issue: refugees? Is it really a refugee issue? Are we misnaming one thing after something else? If not, then why have refugees from the global south attempting to reach Europe through Poland's border triggered such xenophobic outrage across the continent? whereas when millions of Ukrainian refugees flooded Europe two months later, nobody seemed to speak about them in terms of the refugee crisis, let alone regard their existence as a problem?

Despite general claims of Europe transcending chauvinism and racism, the differential treatment and reaction to certain refugees versus others leave us no choice but to examine the identity of the refugees. For it is nowhere but in the identity of the refugees that one can find the reason behind such a stark difference concerning supposedly the same issue. This means that what we call uncritically the “migrant crisis” may not solely result from refugees themselves seeking asylum in Europe, but rather from their own identity. Ukrainians, in their millions, white Christians, despite being refugees, do not seem to cause a crisis, unlike one boat carrying hundreds of African refugees reaching Lampedusa, which as it happened last summer, triggered cries of “migrant crisis” all over Europe with some in the center and far right portraying it as an invasion. Considering the vastly different reactions based on the refugees' identity, one might argue that “migrant crisis” is nothing more than another euphemism for something awful: the rise of xenophobia in Europe.

The adoption of xenophobic stances of the far-right ideology by mainstream political parties in their approach to immigration laws was relatively easy to do, for immigration law, from a European perception, is, after all, targeting others. But it's this tolerance and indifference towards policies that are supposedly targeted at “others” that create a dangerous illusion. It is this illusion of an ability to be far-right toward the other and progressive toward oneself, to be barbaric in the colonies and civilized in the metropole, that always serves as the threshold. A threshold which once reached, allows for the normalization of far-right policies to permeate all aspects of life and political liberty. Isn’t this the case with the authoritarian drift that Europe has been witnessing in recent years?

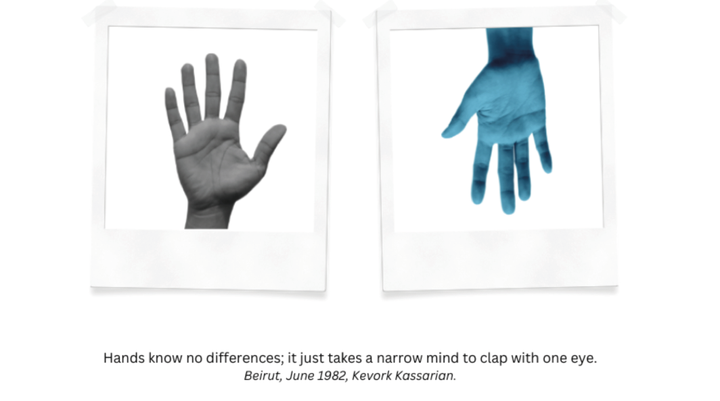

News of censorship, defunding, withdrawal of awards, cultural witch hunts, cancellations of conferences, police raids on cultural events, criminalization of political opposition, are no longer foreign to European countries. Instead, they have become daily occurrences in France, Germany, and many other European states. All this and the far right have not yet arrived to power in these states, and I have not even mentioned a single word concerning the Israeli atrocities in Gaza and the way civilians, particularly Palestinians, have been treated as less worthy and ungrievable by European political figures on the left and center alike. Among them is former French President François Hollande, who has gone so far in defending the war in Gaza as to pseudo-philosophize two distinct kinds of civilian deaths: one is acceptable, which is the death of Palestinians, numbering over 30,000, half of whom are children, dismissing them as nothing more than a collateral damage of a just war. The other kind, which is the only one deemed unacceptable and unjustifiable according to the former president, is the death of Israeli civilians. Similarly, Claudia Roth, Germany’s Minister of Culture, was caught clapping for both Palestinian director Basel Arida and his Israeli colleague Yuval Abraham at the Berlin Film Festival for their co-directed anti-apartheid film, which has won one of the major prizes in the festival. When criticized for applauding the Palestinian winner, the culture minister insisted that at that moment she was only clapping for the Israeli but not his Palestinian partner. Shocking? No? Quite surreal. How is it possible for a socialist president to go down this level, to go this far to the right, to take refuge in a colonial white supremacist perspective for the sake of legitimizing the killing of innocent civilian Palestinians by Israeli carpet bombing of Gaza, as the necessary evil? Seemingly, one would love to know how the German culture minister has managed to craft such an apartheid clap as to reach the Israeli Yuval and not the Palestinian Basel, despite the two being together on the stage at the same moment she was clapping. Again and again, all this and the far-right hasn’t arrived yet to power. And these are only a few examples that come from politicians supposedly on the progressive left of the “cultural wars.”

So, definitely not to the “culture wars,” for if anything needed to be waged now, it should definitely be a cultural and political resistance to the far-right ideology and its rapid normalization and adaptation across political adversaries of mainstream parties on both the left and the right in Europe. A cultural resistance to the destructive ideology of othering, of exclusion, of problematizing the mere coexistence with “others,” of turning their very existence into a fuel to channel hatred throughout society. A cultural and political resistance to the exclusionary racist ideology of the nation-state that is proliferating before our eyes, manifesting itself anew as it takes on a new subject of hatred, of discrimination, of dehumanizing the new other, of creating around their presence an existential threat akin to the fallacy of the “grand replacement” which echoes many of its old anti-Semitic propaganda around a world controlled by Jewish conspirators. A dangerous ideology that, if it comes to dominate in our globalized, multiracial society, will lead us nowhere far from a global civil war. Forestalling and resisting such a catastrophic scenario is the only political-cultural battle worth fighting in Europe nowadays.