It surprises no one so far that religion has become so dominant in almost all the countries of the former Soviet Union. Russia is no exception. Moreover, Russia maintains the leading role in molding the function of the Church in complete accordance with the State. Does this mean that the number of believers in Russia has drastically increased since 1991? Probably not. The reason for a steady clerical expansion resides in the fact that the former Soviet (socialist and communist) ideology has been rejected. For good or bad, this ideology incorporated a set of universalist values which functioned as the justification of the Soviet Empire. At present the rhetoric for constructing a new empire is not valid without a relevant substitute in the form of another universalist set of values. But there is none so far except for the nationalist ideal and the Orthodox Church, which are said to be deeply rooted in the history of Russia.

As we all know, the Soviet economy was voluntarily rejected by the majority of the Communist Party elite in favor of capitalist production – free trade and a market economy. That the free market politics of the 1990s ended in a complete waste of resources and their illegal privatization by the oligarchic clans was already clear by the end of that decade. Such »free capitalist production« was voluntarily transformed by Putin’s team into an accumulation of resources and riches in the hands of those in charge of government administration; i.e., free market capitalism failed. And again the nationalization and governmentalization of capital doesn’t seem »capitalistic« enough. Dynamic investment and production take place in the Russian economy mainly in the natural resource area, but not at all in the fields of new technologies or infrastructure (whether industrial, educational, agricultural, or even military). Along with this, what can really be witnessed is the downshift of what earlier was considered to be mass culture (»cheap« glamour) in favor of the outburst of contemporary art, Orthodox religion and sports – as the »expensive« (refined) glamour. My colleagues in the field of contemporary art, ecstatic about the revival of the government’s interest in art, would vehemently deny that the drastic promotion of these two phenomena (of art and religion) since the beginning of the 21st century share the same origin. On the contrary, they would insist that contemporary art in Russia embodies the antagonism regarding both – mass media and confessional religion.

Nevertheless, it is an undeniable fact that the artistic elite didn’t support the participants in the »Beware Religion« show in 2004, condemned by the Orthodox Church community for »arousing inter-religious hostilities.« Nor do they show any support for Andrey Erofeev now that he is facing trial under the same charge and has already been dismissed as the head of the contemporary art department at the Tretyakov Gallery. In both cases the reluctance to support condemned colleagues is explained away, by citing the poor quality of the exhibition in the case of »Beware Religion« or, in Erofeev’s case, by the fact that he treated the artworks inappropriately as a curator and as a museum director. The argument put forward by the art community against criticizing the system is that the more one fights clericalism directly the more dominant clericalism may become. Such a thesis on the part of the artistic milieu might have been trusted, were it not for its undisguised co-opting by municipal and State policy. Such devotion to the State is not surprising in view of how the Kremlin’s political technologists, new art oligarchy and neo-imperial rhetoric all at once became very positive on the subject of contemporary art’s modernizing values (which somehow doesn’t hamper at all the project of »religious resurrection«). The art community can only be happy about that.

[b]Contemporary art and religion[/b]

The question is: What do church, religion, and autocratic policy have in common with the government’s »enlightening« path, leading to integration into the global culture and economy? And how are the rhetoric of religious and national renaissance related to the rhetoric of welfare, a »modernized« economy and »modernized« cultural production?

The answer could include several aspects. One of the principal ones (already mentioned earlier) is that a new empire has not emerged in place of the older one. The ideology of democracy (which in Russia is seen as a euphemism for the barbaric market economy of the 1990s) has collapsed. Now, the neo-imperial discourse tries to combine the grandeur of the Russian monarchy and its theocratic ties with the Orthodox Church with the Stalinist version of the Soviet Union. In such a perspective the communist project of the Soviets is considered to be merely the vehicle of territorial extension and not at all a radical revolutionary alternative to the homeostasis of »bourgeois« society and liberal democracy (which the communist project, as an anti-western ideology, used to be). Therefore, from the ideological point of view, the new imperial rhetoric of Putin’s administration contains a fatal error: it tries to keep the logic of territorial expansion but rejects the socialist (Marxist) ideology that motivated such an extension in the Soviet »empire.« On the other hand, it also rejects the ideology of democracy, one that could assist to diversify the economy. As a result, what is left as the gluing mechanism of the fake Empire is the set of representative procedures: glamorous architecture, sport victories, contemporary art events (since they legitimize Russia’s cultural and economic integration into the company of successful states) and religion – as long as it stands for the missing ideology.

Meanwhile the effort to keep the retarded model of resource capitalism within the post-industrial global capitalism results not only in gentrification of the bureaucracy but makes it ostensible that this gentrification has a quasi-feudal nature. The feudal economy as well as feudal organization of space is characterized by a scattered multiplicity of provinces headed by a monarch and organized in a strict, vertical hierarchy. Religion and nationalist quasi-ideology are the only means of integrating such split territory, very uneven economic distribution and ruptures in the social strata. But how can artists be part and parcel of such a policy if they do not directly share Orthodox dogmas and if they are not believers themselves?

The answer is simple. A couple of years ago Mikhail Remisov, a conspicuous member of the National Strategy Institute (headed by Stanislav Belkovsky), while presenting his theocratic project of the new »Russian Empire« at the Philosophy Institute, said that he was not a churchgoer, but that he would definitely become one in case he got into Parliament. This means that belief plays almost no role in theologizing policy. On the contrary, sincere Christian believers only hamper the governmentalization of the church and the theologizing of the government and its effort to endow the State’s economic monopoly with »spirituality.« This monopoly does not need any mutually resonating infrastructure, but prefers to be organized in a pyramidal way, legitimizing institutions and undertakings that are center-oriented, and expelling all other centrifugal endeavors. But let us repeat that such centrism does not presuppose any semantic, ideological continuity characteristic for Soviet ideology. It implies that unity and entity are valid only in the frame of grabbed allotments, controlled by the »feudal« »chieftain.« To obey such a disposition one has to acknowledge the sacrality of the chief force, rather than share any mutual belief in the idea. Therefore what really matters is not the fidelity to the Orthodox confession as such, but participation and inclusion in the pyramid – the spiritual clothing of which is that very »magic« transformation of the resource economy into the State’s glory – be it the religious glory of the church in domestic policy, or contemporary art’s cultural glory in foreign policy.

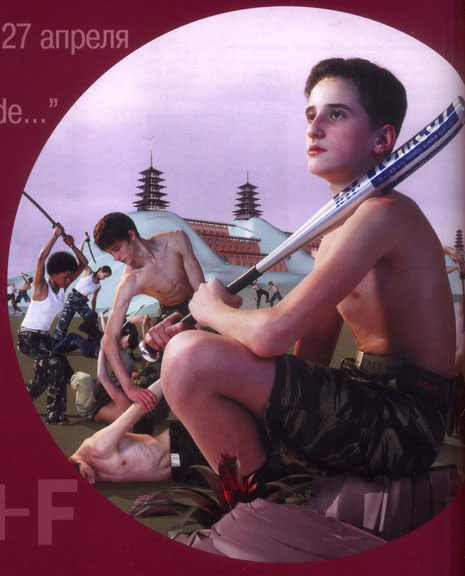

It is therefore not surprising that the main exhibition within the framework of the second Moscow Biennial in 2007, the »I Believe« show, curated by Oleg Kulik, was sponsored and produced by the Moscow mayor’s office and Zurab Tsereteli personally. The curator’s concept had nothing to do with the Orthodox Church, but was meant to manifest the religiousness of art and of creative practices. The art object consequently had to become almost a sacred, cult object, exceeding both artistic as well as market value. (This should definitely be seen as a tendency under the conditions of a neoliberal economy. Many Russian artists were delighted by the recent exhibition at the Centre Pompidou titled »The Traces of the Sacral,« which placed quite a number of modernist, avant-garde and contemporary artworks in the realm of sacrality).

[b]Sacralized art objects[/b]

It was Georges Bataille who said that power and authority detach themselves from the obscene and the criminal by means of religion (in its origin religion hides the utmost sacrilege, which is human sacrifice). They try to turn all that into the Sublime. Likewise, the artist, through shifting his artistic interest towards producing the quasi-cult object, ousts his co-option by the powers that be as well as his hunger for recognition. The contemporary art object, molded as a sacred and cult object, is not of course really a sacred object, as it used to be in archaic times; it is rather a formal (sometimes kitschy) manifestation of a commodity’s sublimation; it is a supercommodity that erases its own previous monetary motivation and does so through inflating its charismatic value and serving as atonement and redemption for the obscene monetary backstage. In other words, such a supercommodity represents an objectified excess value (which according to Lacan is actually the surplus enjoyment usually hidden from production but emerging in the places of representation).

Thus a sacralized art object is not only a supercommodity, but the universal spiritual equivalent, serving as an excuse for wealth and power – just as the Golden Fleece was nothing but a ram’s skin covered with golden sand but stood for the right to the utmost wealth, utmost power, and utmost divinity. We call such objects fetishes or idols.

If one looks at works by Anatoly Osmolovsky (golden tanks, icons or glossy casts of fruit and food), it may become clear that these works are the embodiments of contemporary Russian art as well as of contemporary Russian economy and glamour »ideology.« His works directly manifest the interrelatedness of monetary, authoritarian and religious aspects in today’s Russia. A work of art is destined to be a commodity, it doesn’t even fight to stop its being a commodity. Instead it should find some trick to guarantee an almost impossible effect – to remain desired as a commodity (although a commodity of top price), but at the same time to excel over art by becoming more than just art, to embody something »divine« and priceless but have a direct monetary equivalent.

One could apply such a description of a contemporary art object’s »sacredness« to the purport of the Church as well. In Paul Anderson’s recent movie »There Will Be Blood,« the indissoluble tie between monetary profit and the church as its alter-ego is vividly shown. The oil-industry pioneer (Daniel), before launching production, makes a deal with the young priest (Ilay), who will support the business only if Daniel builds a church and if he becomes the spiritual father of the population living in the area of oil production. Prosperity is promised by the oil business founder almost simultaneously with similar promises by the pioneer of the first church. Money and property should be baptized and blessed to acquire symbolic value and elevated status. The church in turn is the very embodiment of the marriage between the two – the profitable and the spiritual. The church’s spirituality in the film endures because it blackmails the obscenity of monetary power, but at the same time it exists to disguise power’s profitable interests and takes advantage of them. Contemporary art’s function in present-day Russia (and unfortunately not only in Russia) is quite similar to this scenario.

Some art critics, expecting that the »I Believe« show would be a direct apology for governmental policy and Orthodox religion, were disappointed to see that it was just an acid club trip into mysticism, which made them decline their initial critical reproaches. They failed to realize that, although there was no direct apology for government and the Orthodox church in the show, the very function of the Church – to spiritualize »economy,« adorning the backyard of huge incomes – was there. When there is money and charisma (something that art and artists nowadays hunt for), why do we need any art at all? It suffices for art then to be a mere technology.

[b]True faith[/b]

But what about faith, the real kind, if there can be such a thing? In Pavel Lungin’s movie »Island« (the Nika Film Prize winner in 2007) a man tries to repent his crime, committed during the Second World War, by staying in a monastery on the outskirts of the country. He feels quite detached from the official church hierarchy and its institutional bureaucracy, but tries to redeem his sin through prayers, exhausting labor and a magic cure that he renders for ill and suffering visitors. In this case belief is real but it doesn’t seem to be the incentive for social solidarity or a political spirit of change. Instead, it is the instrument for reducing all political potentialities, problems and hopes to the personal relationship between believer and God – something that neither society nor the state are expected to guarantee. Belief, as the individual outcome of all problems, promises swift relief in the situation of factual hopelessness. It guarantees compulsory reconciliation of everybody with everybody else and may as well unleash – if needed – a compulsory hate against enemies.

Thus belief – or rather its instrumentalization – becomes one more remedy for the colonization of the society by its own elite – be it political, financial, cultural or clerical. If such colonization is carried out successfully within the State, it may go far beyond the State’s borders and proceed further with the approval of the fellow citizens.

That such a politics of fictitious love and hatred exceeds the political dimension and leads to the theologizing of politics is evident. In connection with Russia’s latest military actions of »peace enforcement in Caucasus« a famous and very talented Russian writer, Alexander Prokhanov, said that the political aim of Russia in such operations is to prove that Russia is the nation of the divine revelation and that it can be acknowledged as an Empire again. Such a statement can also imply that it is not only money and wealth that can be considered as profit. The utmost profit is utmost power.

Carl Schmidt is right to say that the issuing of a law comes earlier than the act of establishing the government and that this is what makes the sovereign power capable of both – of terminating the law as well as of re-establishing it. What he doesn’t say is what stands behind such dignified power and its decisions. Might it be that the unconscious side producing such a sacred act of law and its termination contains a very hideous mercenary purpose?

When VALIE EXPORT presented her latest work at her solo show during the Moscow Biennial (March 2007) – the multilayered rifle tower over the basin of oil – some said this artistic statement was too political or even too straightforward. Probably it was. But first of all the work was the »simple machine« unraveling the reality usually underlying elevated discourses on the State and its sacred status. It was the pyramidal machine, hiding behind the glossy tower of a sovereign state – a machine for conquering, appropriation and subsequent sublimation of very predatory intentions. This was one of the rare cases when art happened to be true.