Issue 4/2008 - My Religion

On the Ruins of the Soviet Past

Some Thoughts on Religion, Nationalism and Artistic Avant-Gardes in Armenia

[b]The Spaces of Nation: Erasing Erasures[/b]

Very recently in the central part of the capital city of the ex-Soviet Republic of Armenia, Yerevan, the building of the Institute of Linguistics, dating back to Soviet times, was demolished in order to provide visibility for the medieval church once hidden behind it. This retroactive revision marks a paradigmatic tendency in today’s Armenia – to realize itself as a modern nation-state through (and not in opposition to) the post-modern processes of globalization. This curious alliance of global capitalism and nationalist restoration of the Christian past is constructed around their common resentment of the Soviet enlightenment project of modernization. Just as the Soviet authorities radically smashed the deep-rooted religious culture in Armenia, now the Armenian neo-nationalist authorities erase the traces of this very erasure and reload the colonial image of Armenia as an old Christian culture both for promotional and nationalist ends. One of the fruits of this strategy of self-exoticization, testifying to the pronounced demand for the exotic Other still to be found in European museological representations, was a large Orientalist show of medieval Armenian art in the Louvre in 2007, entitled »Sacred Armenia«.

For centuries Armenia had no political sovereignty, and the Armenian Apostolic Church also functioned as a political power. This is why the church in Armenia means more than simply an institution of faith; it symbolizes the nation’s unity. There is, however, the other side of the coin: through supplementing the state, the church simultaneously represents its loss. It is in this sense that the church can be considered an institution of mourning. In this sense, the physical space of the church functions as a symbolic model of the national territory yet to be claimed in reality. In Armenia, therefore, the church has been a driving force behind the nationalist »topographic desire«.1 And it is not by chance that Armenian nationalism emerged from within the church and is associated with the name of the Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian, whose activities coincided with the formation of European nation-states and Europe’s new wave of colonial expansion to the East in the second half of the 19th century. It was a European traveler that Khrimian is said to have told that he had a much older and more precious Christian artifact than what the traveler was looking for in Armenia. By this, he meant the Armenian nation.2 In this statement, Khrimian not only exoticized the nation in the face of the colonial gaze, but also equated the nation with an artifact, an art object, thus constructing the nativist discourse of the nation which now lies at the foundation of the ideology of the ruling Republican Party of Armenia.

Within this ideology, art functions as a locus of nation; art embodies the nation, and as such it comes to replace the ideological function the church performed in pre-modern Armenia.3 Thus, art’s role within this nationalist discourse is, on the one hand, to symbolically construct the absent nation, whilst on the other hand, in doing so, it is expected to trigger actual actions, »national liberation wars«, so that the real site – the national territory – will be conquered. According to Marc Nichanian, in the first move art positively remains within the philological paradigm of mourning but in the second, by being engaged in nativist »Blut und Boden« rhetoric, it overlaps with the process of national suicide and catastrophe.4 However, mourning and catastrophe mutually construct each other, and their dialectic shapes a certain logic of »cultural nationalism«, which gives art a decisive role of responsibility for constructing the nation, as well as triggering and supporting the catastrophic process of gaining it in reality. As a whole, art is in the vanguard of cultural nationalism that deeply affects Armenia. What is then the fate of avant-garde art practices in a context in which art is by definition avant-garde for the dominant power discourse?

[b]Artistic Avant-gardes and the Power Discourse: Meeting Points[/b]

In 1996 a Festival of Arts was held at the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (NPAK is the Armenian acronym) where the national-religious discourse and contemporary art intersected. I would like to avoid generalizing this case, but it reveals some paradigms still functioning in the contemporary art scene of Armenia. The festival was dedicated to the fifth anniversary of Armenia’s independence and was organized by Sonia Balassanian, who is an American-Armenian artist and the initiator of NPAK. In the managerial style classically found among upper-class Diaspora Armenians, Balassanian invited the highest-level authorities of both political and religious elites to attend the show: the head of the Constitutional Court of Armenia and the Catholicos of all Armenians. Alongside the works of contemporary art, Armenian religious songs were performed live in the center. This was an unprecedented event: the power discourse that late-Soviet and post-Soviet Armenian artistic avant-gardes had been positioning themselves against ended up penetrating precisely those avantgardist discourses.

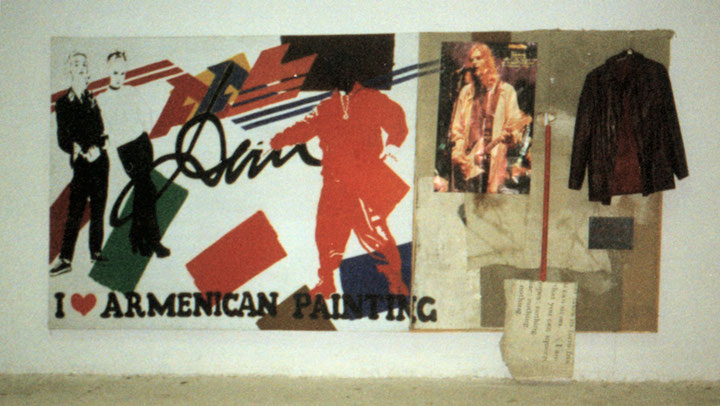

Arman Grigoryan, one of the leaders of the Perestroika artistic-cultural movement »3rd Floor« (1987-1992/1994), took part in the Festival. The work he showed there was an assemblage entitled »I Love Armenican Painting« (1996). This post-3rd Floor project of what the artist called »Armenian Pop Art« was conceived as a queer combination of American Pop Art of 1960s and the stylistic features of the early Fauvist style adopted by Armenian painter Martiros Saryan, who is credited as an architect of the specific genre of »Armenian painting«. Interestingly, Armenian Pop Art conceives of artistic style in terms of nationality, and thus it can be seen as continuing the tradition of 1960s Soviet Armenian modernist painting. Against the backdrop of Khrushchev’s »Thaw« (1956-1964), the young generation of Armenian painters wanted to revive Saryan’s early period, together with some themes and stylistic features of medieval Armenian miniature painting, in order to establish »Nationalist Modernism« as a reaction against Socialist Realism. Significantly, one of the important representatives of these post-Saryanist painters was Grigoryan’s father, Alexander Grigoryan. Politically this discourse, to an extent, informs the liberal nationalism of Levon Ter-Petrosyan (1991-1998), the Republic of Armenia’s first President, who was also shaped by the late-1960s movement, as well as being a medievalist. Thus Grigoryan expressed his full support for Balassanian’s initiative, and indeed even published a text entitled »The Catholicos Blessed the Armenian Avant-Garde« in which he enthusiastically declared that by this blessing »a thousand-year cultural emptiness is filled with freedom« and that finally »the dilemma between cultural progressivism and national identity is resolved.«5

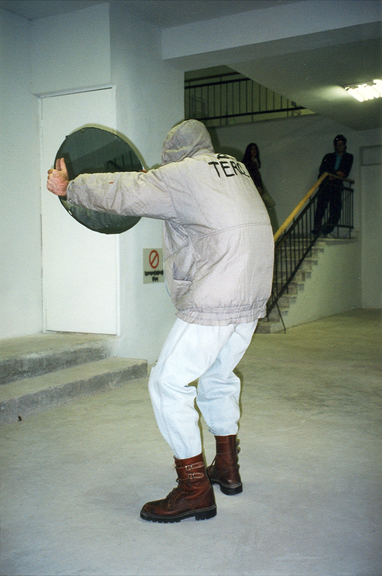

However, Grigoryan’s position was not the only one. Another artist, Azat Sargsyan, intended to do a performance called »Art Terror« against the presence of the Catholicos in the Center. He proposed to reenact the religious rite of foot washing and spray the water on the attendees, including the Catholicos himself. This subversive performance had some strong echoes of Russian Conceptualism, which itself constituted a large portion of Sargsyan’s artistic background. However, Balassanian did not allow the performance to happen the way the artist had planned, as she postponed it to the next day. Sargsyan went along with Balassanian’s decision and the performance took place without the Catholicos, thus losing any claims to subversion.

Apparently various positions held by Grigoryan and Sargsyan actually remain within a broader cultural phenomenon: an old national liberation legend of Armenians, which is constructed by the dialectic between Western and Russian leanings, a dialectic subverted only once – and indeed only temporarily – by the October Revolution.6 At the same time, both positions are constructed in opposition to official Soviet discourse, which in this specific but important aspect situates them structurally on the side of the dominant power discourse and explains the stances they assumed at the Festival. Both the avant-garde and dominant power discourses in Armenia leave Soviet history intact and un-reconsidered. Today NPAK and its policies are an integral part of the alliance between the Armenian Diaspora elite and the neo-nationalist government of Armenia. In addition, it is no coincidence that NPAK has been striving to be incorporated into the museum network established by New-York-based Armenian multimillionaire Gerald Cafesjian. Cafesjian’s initiative again enjoyed the sponsorship of the highest authorities of both the political and religious elites. That means that politically NPAK is closely allied to the dominant ideology of conservative religious nationalism. As mentioned above, Grigoryan’s positions stem from 1960s Soviet-Armenian dissidence and constitute another form of opposition to official Soviet discourse. Politically this is represented by today’s official opposition led by Ter-Petrosyan whose fateful supporter is Grigoryan himself. As to Sargsyan, his positions stem from Russian-style anarchism, which, to cite Lenin, is in danger of converting its supporters to »passive participation in one bourgeois policy or another.«7 In this light, is it by chance that the 6th International Gyumri Biennale, organized this year thanks to Sargsyan’s efforts, enjoys official financial support from the Ministry of Culture for the first time?

Having said this, I hold that the artistic avant-gardes in Armenia need to revisit and rethink their old arch-enemy – official Soviet discourse. And it is praiseworthy that in his recent videos a younger artist, Tigran Khachatryan, is interested in addressing the Soviet revolutionary discourse vis-à-vis the contemporary socio-political and cultural problems he explores. One of his recent videos is dedicated to the 90th anniversary of the October Revolution and is based on another film, »The Beginning« (1967) by Armenian director Artavazd Peleshyan, in turn dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the same event. Khachatryan inserted into Peleshyan’s film the images of boyish activities, left-wing subcultures, sexual relations, street fights, etc. Most importantly however, he appropriated a poem by Kara Dervish, a recently rediscovered early 20th-century Armenian futurist poet. Almost all the images are taken from the Internet, and the work aims at »updating« both Peleshyan and the October Revolution. However, the signs/images used in the video are almost completely decontextualized; it is a space in which everything can meet everything. This practice of »decontextual appropriation« is itself a hangover from the late-Soviet artistic avant-garde, including the Armenian avant-garde of the perestroika era: to appropriate the maximum number of signs betokening the »non-Soviet«, as Boris Groys formulated it.8 Therefore, it is at least problematic to »update« certain contexts without »updating« the very means of »updating«.

[b]Instead of a Conclusion: Using Disused Myths[/b]

In this context, the most pressing issue for Armenian cultural discourses today is the need to revisit the history of the Soviet Republic of Armenia, and most importantly, perhaps, the local revolutionary context of the early years of Soviet Armenia. There was a remarkable generation of Marxist revolutionary intellectuals such as Ashot Hovhannisyan, Tadevos Avdalbegyan, etc. The revolutionary context and the radical democratic views underlying this tradition are now ferociously, almost maniacally criticized by Armenian nationalist academics, paving the way for the »national ideology« they construct.9 The revolutionary discourse these Marxist historians represented was erased, first by Stalinists (they were all either executed or exiled) and now by nationalists; it is a doubly erased discourse, equally unbearable for both.

Interestingly, Hovhannisyan, in his monumental »Episodes in the History of Armenian Liberation Thought« (see n. 7), which he wrote after he returned from exile, argues that the history of Armenians is itself constructed by the continuous acts of erasures and censorships. At the very least this idea can give us an important insight into the understanding and rethinking of the function and effectiveness of avant-garde practices in Armenia. Paradoxically, the radical avant-garde strategy of erasing the traces of the past has a long tradition in Armenian history. Moreover the very myth of the national liberation of Armenians has been shaped by them. What I see as a possible way out is to strategically reanimate what I call »disused myths« instead of attempting to radically subvert the myths in use. For it is perhaps the biggest myth of the avant-gardes to believe in the non-mythical character of their own strategies.

I am grateful to Angela Harutyunyan and Tsovinar Rostomyan for reading and commenting on the earlier drafts of this article.

1 For the term and its discussion, see Stathis Gourgouris, Dream Nation: Enlightenment, Colonization and the Institution of Modern Greece (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), p. 40ff.

2 Khrimian Hairik, Works (Yerevan: Yerevan University Press, 1992), pp. 11-12 (in Armenian).

3 Interestingly, Armenian art was first conceived and interpreted in this way by German art historians in the first half of the 19th century. As Thomas DaKosta Kaufmann puts it: »This is a common theme in German cultural history: since the nation did not exist as a unified state, it existed in German culture. Art provided German thinkers with a form of identity that did not exist in political reality.« Thomas DaKosta Kaufmann, Towards A Geography of Art (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2004), p. 49

4 Marc Nichanian, Catastrophic Mourning, in D. L. Eng and D. Kazanjian, eds., Loss: Politics of Mourning (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2003), pp. 99-124

5 Arman Grigoryan, The Catholicos Blessed the Armenian Avant-Garde, Garoun, No.1, 1997, p. 93 (in Armenian).

6 For the history of the Armenian liberation legend, see Ashot Hovhannisyan, Episodes in the History of Armenian Liberation Thought, 2 vols. (Yerevan: Academy of Sciences Press, 1957, 1959) (in Armenian).

7 Vladimir Lenin, Socialism and Anarchism (1905) in Lenin, Collected Works, vol. 10 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1965), p. 74

8 Boris Groys, A Style and a Half: Socialist Realism between Modernism and Postmodernism, in T. Lahusen and E. Dobrenko, eds., Socialist Realism Without Shores (Durham, London: Duke University Press, 1997), p. 82. I discuss this practice in relation to the 3rd Floor in my »Hole in the Sky«, The Internationaler, No. 1, 2006, p. 8

9 Cf. Sergey Sarinyan, The National Ideology of Armenians. Yerevan 2005, p. 90–91, 93 (in Armenian). As part of his performance »Sweet Repression of Ideology« David Kareyan cooked the first edition of this book in 2000. I analyze this performance in »Hole in the Sky« (c.f. footnote 8), p. 9