Issue 1/2009 - Art on Demand

Breaking out of isolation

In Libya a cultural springtime will not be long in coming

The installation by Libyan artist Hadia Gana in the inner courtyard of the former French consulate in Tripoli’s old town is reminiscent of a Japanese Zen garden: on painstakingly raked white gravel lie hollow ceramic stones, with old photos and letters from the artist’s family silk-printed on them. Visitors step hesitantly onto the gravel, pick up the haptic ceramic works carefully, turn them around to look at the texts and photos: they hear a small stone in the interior rolling around as they move the stones back and forth, and then put the stones carefully back down again. Gana’s stones represent moments of remembering, they confront viewers with their own history and are intended to encourage reflection. Hadia Gana’s (interactive) installation stands out as an exception in the Libyan art scene with this. Works related to a specific space, a personal design language and the way in which viewers are expressly included in the work are rather rare in this relatively young art world that has only begun to emancipate itself from its marginalised position over the last few years.

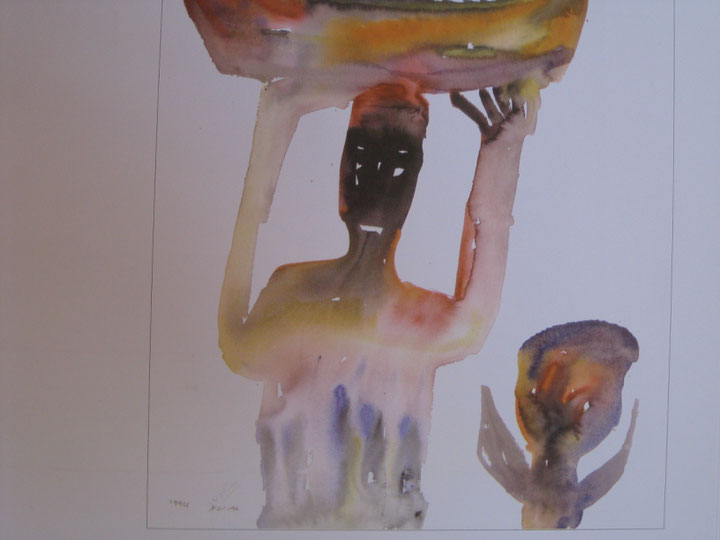

Society in the desert state is shaped by Bedouin culture, a lifestyle that is traditionally nomadic, meaning that it enjoyed a rich narrative tradition, whilst owning artworks simply proved cumbersome, given the need for mobility. As a result, the fine arts have developed as a fairly recent phenomenon in Libya as in other Arabic countries. In addition, during the many years when this alleged rogue state was isolated politically, there was little outside impetus for a lively art scene to develop. Furthermore, in the light of the traditional values defining Libyan society, in which the individual is part of the whole and membership of a tribe or family is more important than personal, artistic development, there is no scope either for the Western concept of individualism. Ali Ezouik’s bright watercolours of blurry fruit, fish and people, Ali Albani’s abstract landscapes and the meter-high geometric steel sculptures by Loay Burwais are particularly striking in this small art scene, precisely because they have their own artistic imprimatur.

In contrast, painting modelled on the work of others has particularly influenced the development of most artists in Libya. Many art students from Libya study at the academy in Rome. During their stay they primarily copy landscapes, portraits and sculptures by classical Italian artists. Similarly, at the Academy of the Arts in Tripoli it is standard practice to draw and paint from photos or (clothed) models. Reproducing reality as accurately as possible is held to be a sign of artistic quality in Libya. A striking number of works correspond to realistic notions of art: desert landscapes with nomads, views of harbours or impressions of the old city in Tripoli. Most sculptors produce abstract works, perhaps also because images of people and animals were proscribed in traditional Islamic culture. It was forbidden to produce an image of anything that breathes, in order to avert the risk of idolatry. The influence of this consideration can also be felt in Libyan contemporary art. Video art, installations or performances are alien concepts. There are no nudes in paintings, drawings or sculptures: not so much because this is actually forbidden in Libya but rather because it is not acceptable in terms of the rather strict social codes. It is striking that the sculpture of a naked girl with a deer that an unknown Italian artist set in the middle of a fountain in downtown Tripoli during the Italian occupation (1911–1943) has not been removed even today, as the inhabitants seem to appreciate it.

Exhibitions by local artists are shown regularly in the gallery Dar Al-Founoun (House of Art) in Tripoli’s 7th November Street. The gallery – established in 1993 by the artist Ali Ramadan and now directed by two entrepreneurs – is one of the few galleries in this port city that works commercially and professionally. Art supplies are for sale on the ground floor of the building, whilst the actual exhibitions are held in the basement area. Although some artists complain that gallery owners could be more committed, exhibition openings are regularly well-attended. Sales are still modest: purchasers are primarily expats with just a few Libyans. The real art collectors are above all foreigners together with a few local artists. In the evenings the artists often meet in the gallery, as well as in the former French consulate, which has been restored by Tripoli’s town council and regularly hosts exhibitions and well-attended poetry readings. A few hundred metres from the consulate the city rents out small studios to around ten artists – exclusively men, as social values and standards would not allow female artists to rent a studio outside their own home (Nonetheless it should be noted here that Libyan legislation is the most progressive in the region in respect of women.)

One looks in vain for museums of modern and contemporary art in Libya. None are planned as part of the capital’s urban renewal either. As artists are often labelled as individualists, they do not fit into the state theory of the »Libyan-Arabic Socialist People’s Jamahiriyah« (the state of the masses), in which the individual is subordinated to the good of the community. The only individual to stand out from this mass of the people is the Revolutionary Leader himself. Art in the public sphere is limited to meter-high portraits of Muammar al-Gaddafi –in an officer’s uniform, in Bedouin robes or in African costume to underscore his pro-African attitude. The portraits hang at central city intersections and decorate government buildings as well as large residential blocks at strategic transport nodes. This personality cult is one reason why no Libyan artist can assume a really outstanding position in the art scene. The exhibition »The desert lives«, which was shown in 2002 in several European cities and presented art from Libya, primarily showed the oeuvre of the architect (and self-proclaimed artist) Saif Il-Salam. Saif is one of Gaddafi’s sons and the exhibition thus confirmed the assumption that the Gaddafi clan does not simply determine the country’s political and economic fate but also influences the Libyan art scene.

If you approach this art scene with the customary prejudices, thinking that Libyan artists are obliged to criticise political structures in their works or if you assume that you will find art in the vein of social realism of the kind familiar from the former GDR or the Soviet Union, then you not only fall prey to a cliché but also ignore the context in which artists here work; in contrast to European colleges of art and academies, artistic training here is at a low level. The Libyan school system does not encourage creative and self-reflective thought. Instead priority is given to learning texts by heart and to copying from models. Looking for art students who seek to grapple critically with politics and society seems rather misplaced, when one sees that at the arts faculty in Zawia the students are busy doing handicrafts with toothpicks and matchboxes.

Critical voices are however to be found in the Libyan art scene. For example, the satirical drawings and caricatures by cartoonist Mohamed Al-Zawia. These are critical of the political scene and reflect on the hypocrisy and deplorable circumstances in Libyan society. However his expressive works also address the West’s pro-Israel policy, the UN’s sanctions over the Lockerbie question and how much power the US dollar has over Libya’s economy. The only taboo is criticising the Revolutionary Leader. Al-Zawia’s drawings are published in a number of books and local newspapers; he has an excellent reputation in the art scene and is also held in great esteem amongst the general populace, precisely because he knows just how to hold a mirror up to society with a pinch of humour and sarcasm.

[b]Expats and returnees[/b]

Since the embargo was lifted in 2003, Libya has opened up economically. Money is coming into the country and there is a lot of investment, not only by the government but also in the private sector. Libya seems to be being catapulted from Gaddafi’s notion of Socialist idealism towards market-economy liberalisation. The political headaches are a thing of the past: the Lockerbie trial has drawn to a close, alleged poison gas facilities are being disassembled and the Bulgarian nurses have been released. Now the West wants to do (oil) business with the desert state. Many Libyans who left the country in the 1980s expect to benefit from the economic upturn (with a growth rate of c. 9 % in 2007) in their home country and have been coming back. At the time when they emigrated, the government still kept the desert state in an iron grip politically and economically. The Libyan-British author Hisham Matar gives an impressive description of the mood of those days in his book »In The Country of Men«: public executions broadcast on television, queues outside state supermarkets and the authorities watching everything and everyone. The many Libyans now returning are a sign that the mood in the country is one of transformation and new developments. People are convinced that the changes will not be reversed once again. A growing number of local artists are also benefiting from the new developments, as they have begun to receive both private and public commissions.

Europeans’ persistent questions about censorship and state control are however at least as inappropriate as assumptions that artists in Libya are repressed and have no opportunities to develop their talent. To cite just one example, Hadia Gana – she studied ceramics at the Al-Fatha University in Tripoli and did her MA at Cardiff University in Wales – is currently painting a mural for the Libyan government’s new guesthouse. One would be jumping to conclusions if one simply assumed that this commission is related to Gana’s political convictions rather than to the quality of her work. As the economy has gradually opened up, political détente has slowly begun to unfold in its wake. Whilst there is still state censorship, this has hardly any influence on the fine art scene, as only a small elite and a group of expats take any interest in contemporary art in Libya. In contrast it is much harder for writers and poets – novels and poetry are very popular with most Libyans and as a consequence the state monitors every word that is written or spoken.

In domestic politics there is currently talk of a power struggle between the old camp around Mohamed Gadaffi and the new guard, which supports his son Saif Il-Salam, who many Libyans presume will be his father’s successor. Saif has succeeded in gaining loyal support from a group of reform-minded people with experience and an appreciation of quality. They have in the meantime taken up posts in ministries, administrations and other state bodies. When it comes to commissioning artists, nowadays the criterion for selecting an artist is not so much their personal loyalty to the political authorities, but instead the quality of their work. One example is the commission given to Hadia Gana. Her works often assume biomorphous forms, which no longer seem to be modelled on any kind of specific object. Gana experiments with various materials and succeeds anew over and over again in creating harmony between her art and each particular environment, whilst also according viewers their own place within this setting. The patience and persistence with which she urges her students to work independently and creatively becomes strikingly clear if one attends her classes at the academy.

Quite apart from the government’s activities, more and more firms are also deploying art as part of their marketing strategies. As a result Hadia Gana has recently received a number of private commissions. She has designed bathrooms in various private residences and was commissioned by a young Libyan businesswoman to design the ceiling painting in the café of the new Mango shop; the Spanish chain producing women’s clothing, which is soon to open its first outlet in Libya. Gana’s spiralling shapes harmonise perfectly with the modern design of the boutique in Gargaresh Street, » Tripoli’s Champs-Élysées«. It is now lined with shops such as Versace or Gucci, expensive restaurants with cool design and hip fashion stores. Designer and architect Loay Burwais created the façade and interior of one of these boutiques.

Burwais returned to Libya back in the 1990s. He had lived with his parents and sisters for over 20 years in Greece, Iraq and France, and had studied architecture and design in Paris. He first opened an atelier for metal sculptures in Benghasi. By now an international team of 36 produces his designs in a large factory building in Tripoli. His office designs private houses, shops and terraces, as well as furniture, banisters and garage doors. Most of these are produced in welded steel, with his hallmark curving lines and geometric shapes. His clients are entrepreneurs, doctors or private households that have discovered a passion for design. Currently Burwais is designing a café on Gargaresh beach, where he plans to organise temporary exhibitions to offer his guests an opportunity to encounter art. The magnitude of his idealism becomes clear if one considers that Libya has neither a gallery scene nor any form of art criticism. In addition, for the majority of Libyans simply making ends meet from day to day takes up most of their energy, for the economic recovery benefits only a small stratum of society: most men have several jobs to keep their family or to finance a forthcoming wedding. A few years ago, Burwais was one of the initiators of the first large exhibition of contemporary art in Libya – »Rivages 2005«. 34 artists from six different countries showed their works in his factory hall: paintings with abstract landscapes, nomads and figurative pieces, photos portraying everyday life in Libya, and glass and steel sculptures. It was surprisingly successful. Visitors flocked to the exhibition in much larger numbers than the organisers had envisaged, which meant they had not applied for permission, and that as a consequence Burwais was questioned by the authorities on a number of occasions. The government does indeed remain present everywhere.

[b]Art and urban planning[/b]

Libyan entrepreneurs have also discovered the contemporary art scene thanks to the economic resurgence. Advertising and marketing agencies in particular frequently organise selling exhibitions with works by young Libyan artists for image-boosting purposes. Artist Salah Ghith was commissioned by the advertising agency El-Najem to organise a group exhibition on the second floor of an office building in Ben Ashour Street. Najla Shifte’s work stands out among the realistic landscapes and townscapes. The young artist outlined the shapes of around 100 feet with black cord on a red surface. The work references the Hajj ritual in Mecca, in the course of which hundreds of people died a few years ago when there was suddenly a panic amongst the crowds of pilgrims. Shifte’s development of a personal style is not always appreciated in Libya. Artist colleagues advise her to let herself be guided more by historical models and to seek to reproduce reality.

Social values and standards still determine what is painted and how it is painted. As nudity may not be shown in exhibitions in Libya, Mohamed Abumeis created an abstract form of naked female bodies for his exhibition in Dar Al-Founoun. The works are reminiscent of informal painting and make frequent use of warm orange, red and yellow tones. The exhibition is the first presentation of his works in Libya since he returned from Europe. Like many Libyan artists he studied abroad with a grant: he was in Manchester for four years. That makes it surprising that his artistic role models are not really the Young British Artists, but that he is influenced instead by more classical figures such as Rembrandt, Antonio Tapies and Edward Munch. It is striking how few artists in Libya take an interest in the international art scene. Libyan artists often ask their European guests in surprise why they should seek direction in what other artists abroad are doing. Meriam Abani, for example, has little interest in art produced outside the confines of her own country, even though she studied in Rome and lectures at Tripoli’s faculty of art.

This is not an arrogant attitude. Many aspects however only begin to make sense when one recalls that the general public in Libya had almost no opportunity to have contact with other countries in the 1980s. Neither the Internet nor satellite television existed, and any kind of contact with foreigners was viewed with suspicion. Abumeis and Abani were teenagers back then and the repressive mood of those years has left a permanent mark on their thinking.

However, there are now initiatives where artists’ opinion is in demand. Hadia Gana recently became the only artist in an advisory body made up mainly of architects and urban planners. This body, initiated by Ahmed Lakhder, takes a close and critical look at planned new-build projects in Libya, for which an annual government budget of c. 56 billion Euro is earmarked. Lakhdar is the director of Engineering Consulting Office for Utilities (ECOU), a sort of urban planning ministry. Libyan, Swedish and Swiss architects work together here on a facelift for Tripoli. Lakhdar, who studied architecture in Paris, is one of the Libyans that returned to their homeland full of conviction and zest for action. At his drawing board he proudly explains his ambitious plans for the Libyan capital, spearheaded primarily by Gaddafi’s son, Saif Il-Islam. Renowned architects confirm the ambitious project plans, with a total budget of 15 billion Euro: Norman Foster drew up a design for the eastern port area, and Zaha Hadid sketched out blueprints for the new congress hall and the military museum. In the south, French landscape architect Gilles Clement is to lay out a 24,000-hectare green belt of forest around Tripoli. As negotiations are still underway on the final contracts, which have yet to be signed, details of the projects are so far not available on the web pages of the various European star architects involved. Illustrations on the fencing around construction sites in the inner city evoke associations with Dubai: five-star hotels soaring upwards, futuristic skyscrapers and a new airport, which is to handle twice as many passengers per annum as Charles de Gaulle.

The objective is to implement part of the plans this year in time for the 40th anniversary of the Libyan revolution, although the port of Tripoli, for example, does not yet have sufficient capacity to handle the construction material needed. In the meantime Ahmed Lakhdar has had squares in bright neon colours affixed to the façade of his office building – a pleasing sight in the monotonous cityscape of Tripoli, even if at first many passersby criticised the choice of colours.

Whilst the changes in the Libyan cultural scene are minimal, they are nonetheless visible and awaken hopes. The personal commitment of some artists and architects is very promising, even if it is mainly elite that has the money, time and interest for exhibitions, poetry evenings and art projects. The dynamism of the economic renaissance in Libya is noticeable everywhere you turn, and this upturn brings such enormous benefits for culture that there are good reasons to be curious as to the outcome.

Translated by Helen Ferguson