Issue 1/2009 - Net section

Cube-shaped receivers

An exhibition recapitulates milestones in the development of an art of sound

In the photograph, a woman lies sleeping while a man wearing headphones listens to a tape. One jarring detail mars this otherwise peaceful scene: a microphone has been placed above the woman’s head, suggesting that the man is listening to the sounds she makes in her sleep. The visitor can also listen in, by placing a record on the nearby turntable. As the noises, garbled words and breathing sounds emitted by the sleeper waft across the surrounding space, the boundaries between the fictional scene in the photo and the reality of the gallery merge and interweave. The work highlights the complementarity of sound and visuals, and the differences between our auditory and visual systems of perception, interpretation and representation.

This piece by Laurent Montaron, called »Somniloquie« (2002), is just one of the thirty-odd works on show at an exhibition entitled »Sound of Music«. Along with the other installations, videos, paintings, photographs and objects on display in Lille, it highlights sound’s capacity to give a new dimension to an artwork and shows that it constitutes, like images, one of the raw materials of contemporary art.

It was John Cage who paved the way for sound’s entry into the art world: not only did he open up music and art to all kinds of sounds, including the noises of daily life, but he also drew attention to the possibilities ushered in by the interaction of different art forms, including music – most notably in the celebrated multi-media event he organized at Black Mountain College in 1952. The exhibition displays his colourful graphic contribution to a mail art project, »Diary: How to Improve the World« (1968), while his ideas about music are reflected in the works of the other artists present. The Fluxus artists, represented here by George Brecht, followed in Cage’s wake, questioning the practice of music and the rituals surrounding it. Brecht’s installation, »Ten Event Glasses« (1984) consists of stands bearing transparent sheets of glass that invite the visitor to view the world from an artistic perspective, as an ever-changing musical score.

The second turning point in the development of sound-related artworks was technological. As electronic instruments evolved from large-scale institutional systems into miniaturized user-friendly equipment, a number of pioneering artists operating on the margins of the music and art worlds began putting these relatively cheap technologies to creative use. Transcending the temporal and spatial constraints of the concert hall, they created sound-based works that visitors could experience in their own time, while moving freely around the space. Christina Kubisch developed her own magnetic induction system in the early 1980s. By holding cube-shaped receivers to their ears, visitors could listen to sounds of the sea on one side of a room and to breathing sounds on the other side of it. They could mix the sounds by moving between the two fields, creating a composition of their own. Another artist, Bernhard Leitner, began diffusing sounds along series of speakers in the 1970s, drawing lines of sound in space and creating ephemeral sonic architectures that visitors could enter and explore. In the years that followed, a host of artists began using spatialization techniques, electronic sound-producing gadgets and interactive technologies to fashion complex multi-faceted ambiences and soundscapes. Appreciated by a small, albeit loyal, following, these works deployed sound in new ways, questioning its use and meaning as well as the technology used to create it.

Recent advances in computer technology have greatly facilitated the work of artists using sound, while ushering in a new phase. With the advent of multimedia and the capacity to programme sound and visuals instantaneously and simultaneously, sound is no longer a little-explored material confined to the outer margins of the art world. Today artists from all backgrounds exploit its potential, creating all kinds of works. These range from installations in outdoor public spaces and urban environments, which draw attention to the wider sonic environment, through to live audio streams and pieces using mobile telephones and other mobile music technologies, which question received ideas about space and time. Works that make overt use of new technologies tend to be categorized as multimedia, while installations in which the focus is on sound as such are generally shown in sound art festivals. Pieces that take a critical approach to sound and music, building on the legacy of artists such as those in the Fluxus movement, have found a place in museums and galleries.

Music-related artists’ videos fall into this last category. Unlike video clips, in which the focus is on the performers and the music as such, the emphasis in these pieces is on sound and music’s associative and referential qualities. At »Sound of Music«, Thomas Galler and Erich Weiss’s video, »Bela Lugosi’s Dead« (2008), explores the legacy of Ceausescu, portraying him as a modern-day vampire who exploited his people. It shows a young Romanian rock group who perform a song at Galler and Weiss’s request about the death of an actor famous for his role as Dracula. The harshness of the music and the unrelenting intensity of their performance give a sense of how Ceausescu’s reign of terror continues to weigh down on the population of Romania some twenty years after his demise. This work blurs the borders between past and present, legend and fact by means of the evocative power of music.

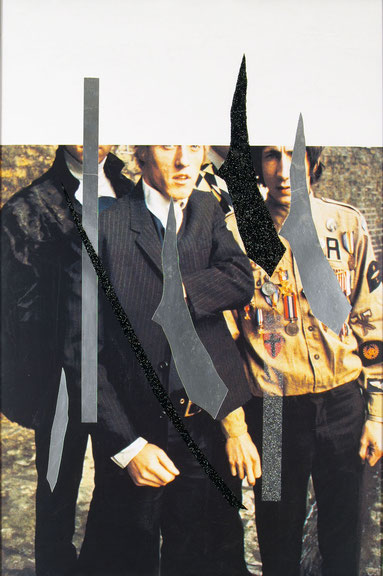

Other artists at the exhibition dispense with sound and music, resorting instead to silence. John Cage explored the latter’s significance in his legendary silent piece »4’33”« (1952), while his unconventional scores silently conjured up new and unknown sonorities by means of lines, points and graphic elements. At »Sound of Music«, Meredyth Sparks shows that a photographic image can also evoke sound. In her »Untitled (The Who I)« (2006), strips of aluminium cut across an image of the group, echoing the destructive energy of their music. Its sound seems to ring in the viewer’s ears, bringing the photograph to life and endowing it with considerable symbolic power.

Works consisting of sound alone likewise open up intriguing perspectives, although they are few and far between in exhibitions. Conceptual artist Robert Barry’s »Variation no. 1« (1977) is the only piece without visuals at »Sound of Music«. Here 178 unconnected words are read out at regular intervals, giving the piece a form and structure and filling the space with their fragile, ephemeral presence. When listened to in succession they do not make sense, yet the sound of each individual word triggers a multitude of associations as it lingers in the visitor’s mind. As Barry’s piece shows, works comprised only of sound need time to unfold and space in which to deploy themselves in order to be fully appreciated. However opportunities for them to do so are few and far between in our visually-oriented art world.

»Sound of Music«, organized by FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais, was shown from October 10th to October 26th 2008, at Tri Postal, Lille, France. Between April 4th and June 14th 2009, it will be on view at Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK.