Issue 1/2010 - Globalismus

Time to re-stage the world

Globalism as a reflection on, and antidote to, globalisation

I would like to begin with an act of terminological ground-clearing. To me, as a cultural theorist and curator based in India and reflecting and working trans-regionally, the term \\\'globalism\\\' has come to bear a specific experiential, conceptual and strategic meaning. Globalism, for me, is not only a theoretical construct but the foundational premise on which my practice is based. I see globalism as a productive mid-ground, shifting in its applications, yet resolute in its shape: a position from which to critique both the self-insulated perspectives of the regional or the national, as well as the potentially vacuous pieties of the \\\'transnational\\\' as elaborated in the rhetorical space made available to academics and cultural practitioners by a so-called globalised world.

It would be useful to unpack this proposition before we proceed further. Firstly, globalism allows me to stand at an enabling rather than an alienating distance from the logic of regional and national narratives, and to see how the destinies of particular societies and countries are not the expression of an imagined and original mentality and culture. Rather, the adoption of a globalist position allows me to see that these destinies are shaped through the mediation of intricate webs of exchange, conflict, diffusion and mutuality, which may sometimes extend across oceans and continents.

And secondly, and simultaneously, globalism provides a bracing antidote to the zero-gravity conceptions of theorists so preoccupied with their negotiation of the institutionality of Euro-American academia, that their understanding of the world has become evacuated of politics and is no longer anchored in the material thematics and urgencies of specific locales.

As a conceptual tool, globalism thus allows me to break free of several restrictions, some that are external, others that arise from within. If, for instance, globalism points in the direction of world-mapping and world-making that preceded the advent of colonialism, it also proposes forms of affinity and communication that cut across the boundaries of a model of resistance that has now become redundant – the divisions between the centre/periphery, advanced/developing, and coloniser/postcolonialist. In any case, the endemic trans-regional flow of people, ideas, goods and services has ensured that the postcolonial is everywhere, that identities are played out as performance rather than as inheritance, and that (to twist Fanon\\\'s celebrated image) the colour of the mask offers no clue as to the possibly surprising colour of the face beneath. It is time to restage the world.

Before spelling out a modest proposal for the restaging of the world, I would like to situate globalism, as I have elaborated it here, as an expression of what the theorist and curator Okwui Enwezor has called the \\\"will to globality\\\". This will to globality is not the monopoly of a nation-state that has benefited from the machinery of global capitalist enterprise, but may arise in any region of the world, and articulates that region\\\'s desire to belong to and participate in discussions, movements and aggregations across the planet.

In a reactive sense, such a will to globality can convey a cultural response to globalisation, to the manner in which a highly interconnected world can subject the regional to transnational flows, to the mobility of military and diplomatic influences, and to interlocking transnational arrangements, all formulated within a global paradigm of power. In such a context, globalism is a condition in which you could mobilise a measure of bargaining power for yourself.

But more importantly, I would like to read globalism, not as a reaction to globalisation, but as the audacious and positive reflection of a desire to release the cultural self towards others in a manner that bypasses dependency and embraces collaboration, making for a productive cosmpolitanismcosmopolitanism. We could list numerous examples of globalism in this spirit, especially during the period before globalisation.

From an Indian perspective, I would think immediately of globalism as being embodied, variously and in widely removed periods and situations, in the philosophical cross-pollination between Greek and Indic thought in the classical and early Christian eras (McEvilley: 2002) and in the pan-Asian ideal elaborated in the correspondence between Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin during the early 20th century (Bharucha: 2006); in the founding, by Nehru, Nasser and Tito in the 1950s, of the Non-Aligned Movement as a position equidistant from the USA and the USSR during the Cold War and demarcating the Third World as an alternative space of self-determination; and, in the cultural sphere, in the establishment of the Triennale India in the late 1960s by the writer and cultural organiser Mulk Raj Anand, as a key platform for the manifestation of a globalisation from the south.

As a tool with which to restage the world, I would propose the concept of a „transient pedagogy“. This concept emerges from recent theoretical work conducted by Ranjit Hoskote and myself around the contemporary condition that we have termed as \\\'critical transregionality\\\'. Our interest is to remap the domains of global cultural experience by setting aside what seem to us to be exhausted cartographies variously born out of the Cold War, area studies, late-colonial demarcations, the war against terror, or the supposed clash of civilisations.

In place of these outplayed, even specious cartographies premised on the paradigm of the \\\'West against the rest\\\', we propose a new cartography based on the mapping of continents of affinities, and a search for commonalties based on jointly faced crises and shared predicaments. What platforms and assemblies can we develop, to identify and work through such continents of affinity? One possible model is what we have called transient pedagogy, the constant process of learning by which travellers negotiate terrains that can transform themselves radically and without warning. Within such a transient pedagogy is implicit the project of recovering alternative and anterior histories of dialogue and mutuality, through which to disclose the hidden contextual sources and genetic strains of contemporary cultural selfhood. In place of the scalars of traditional history, we privilege the invisible vectors that have effected historical transformations on both an epic and an intimate scale through the centuries, and continue to do so.

Since the early 1970s, when we first began seriously to question the authority of Euro-American master narratives, our discourse has been staged in a comparative mode in terms of our entanglements with Western narratives. Fundamentally, we have phrased these entanglements through the vocabularies of colonialism and imperialism: a condition that the Philippine novelist and nationalist Jose Rizal evocatively termed as the \\\'spectre of comparisons\\\', el demonio des comparaciones. As the discourse produced by postcolonial theorists through the 1980s began to dismantle the primacy of Euro-America, turning the global metropoles into contested centres, the traditional and somewhat developmentalist centre-periphery model was gradually displaced by a model of the world where individuals, communities and nations are connected by surprising webs of information and unexpected alliances across borders. In such a situation, the former periphery becomes, in actuality, available as a garland of emergent centres.

Through the medium of transient pedagogy -- so called because it is provisional, tactical, and concerned with possibilities of disclosure -- what we may achieve is the disclosure of alternative starting-points for the global contemporary. Through this means, we may make multilateral connections and possibly even recover pre-modern and pre-colonial connections, we can develop new and de-territorialised cartographies. We could look, for instance, at the connection between Syria and Sinkiang across the Silk Route, or the linkages between Cochin, Venice and Nuremberg through the Indian Ocean pepper trade, or the imaginary line between Eastern India and South-east Asia, along which merchants, scholars, storytellers and adventurers sailed across, carrying the Ramayana as well as Hindu and Buddhist thought (Trojanow and Hoskote: 2007).

We could also, for instance, retrace the trade connections between Antwerp and Surat during the Mughal period: this 17th-century trade was based on luxury items like diamonds, carpets, shawls and silverware. A less well-known story of exchange during this period involves Rembrandt\\\'s archive of Mughal drawings, works that would have come from the ateliers of the Mughal empire, and the flow of a corresponding trove of European paintings in the Mughal courts.

Can we imagine a world that had other centres than New York, Brussels, Zurich and Shanghai? Can we conceive of a polycentric world governed from Agra, Beijing, Palermo, Damascus, and Mexico City; and whose financial centres were Basra, Bremen, Venice and Alexandria? But this is what the atlas of the world -- without Mercator\\\'s distortions -- would have looked like, during the period 1300-1800.

Transient pedagogy is proposed as a mutable model, one that has an in-built, self-disruption device. Rather than founding an institution and then instituting pedagogy within it, we would begin in reverse, with a pedagogy that can be constantly re-evaluated and refined. While conventional pedagogies are based on master narratives, transient pedagogy would encourage the production of what, following Harrigan and Wardip-Fruin (2009), we would call \\\'vast narratives\\\'. These are a cross-media phenomenon, evolving through the translation of material from one medium to another, extending in duration across considerable spans of time, and re-distributing memory over a series of caches. Vast narratives, in our framework, would be forms by which deep memory can be relayed and kept in play by diverse means, so that the hybridities of the past can be transmitted into the present.

In the process of developing a transient pedagogy, we would also consider a variety of prior models of the production of knowledge, including oral transmission (the Upanishads), peripatetic journeys (Socrates, Plato), dialogues (the Buddhist Milinda-panha or \\\'The Questions of Menander\\\'), so that we may remind ourselves that academic inquiry was originally meant to free knowledge and make it available and refine the self, not to lock it down and hoard it. The methods of pre-modern philosophy may have been provisional and mercurial, but they were intended to transform the consciousness: these are values worth recovering for our present confrontations with the world.

*

As examples of transient pedagogy, I would reflect on two art projects that prompt a reassessment of current certitudes, initiate a new learning process and help mobilise new reserves of insight and knowledge: Sheba Chhachhi\\\'s \\\'Winged Pilgrims: A Chronicle from Asia\\\' (2007) and CAMP\\\'s \\\'Wharfage\\\' (2009).

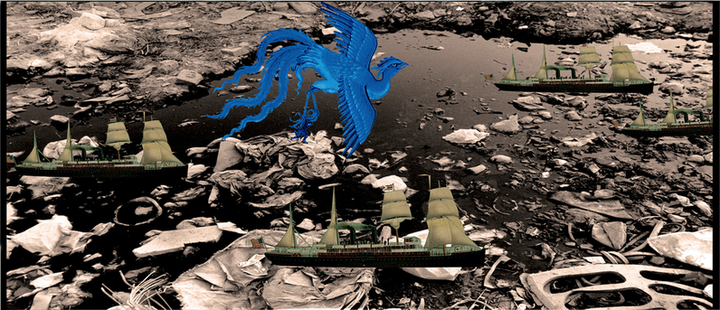

By weaving a fiction around mythic birds from various Asian traditions -- the swan, the phoenix, and Garuda, the solar eagle -- Chhachhi proposes Asia as a conversation crafted from cross-fertilisations among cultures by the storytellers, image-makers, merchants and monks who crossed the Silk Route for centuries, creating a rich internationalism, an Asian cosmopolitanism. Ironically, India and China -- global economic powers that once traded in silk, jade, ivory and turquoise, cherished both by traders and by pilgrims as sacred treasures -- are today linked by the dumping of techno-kitsch and warily similar positions on global warming and environmental deficits. Chhachchi melds past and present, the mystical and the material: her flying magicians must contend with the presence of men in anti-contamination suits culling birds, modern-day saviours who paradoxically protect the earth by killing its species. And the battery hens in her work, moving to the rhythm of a conveyor belt, remind us that the winged pilgrims have been imprisoned in a television that is not really a television, in landscapes that are artefactual, in a movement that is illusory. She thus privileges the wisdom of the traveller while drawing attention to the violence of ethnic, sectarian and national divisions that cut against all passage and exchange (Adajania: 2007).

For the 9th Sharjah Biennial, the Mumbai-based artists\\\' platform CAMP conceived and developed a richly informed project of retrieval and transmission, titled \\\'Wharfage\\\' (2009), which reanimated many pre-colonial maritime histories of exchange, dialogue and collaboration around the Indian Ocean littoral. A book and radio broadcast project, \\\'Wharfage\\\' wove these histories into a contemporary predicament veined with the pressures of globalisation, the dangers of piracy and the presence of failed and failing states. Vitally, this project drew attention to the fact that there have been globalisations before globalisation: transregional networks of trade, pilgrimage and the circulation of goods, people, services and ideas, that linked the world in diverse ways. The authors of CAMP\\\'s Wharfage document write: \\\"What does direction mean? Kierkegaard speaks of love as an arrow, without reciprocity, in which to love is full, self-sufficient. It means that we are able to speak of parasites and pirates, with affection. It means that the fundamental unit is not mass, it is momentum\\\" (CAMP: 2009).

To restage the world is to renew oneself: by rewriting the script of the world\\\'s performance, recasting its choreography, redistributing the speaking and the silent parts, changing the beginning, the middle and the end, and tweaking the tempo of these phases. Artistic positions such as those of Chhachhi and CAMP demonstrate how these momentous gestures of world-making and self-renewal may be initiated.

Select Bibliography

Adajania, Nancy. \\\'Travelling to the Realm of the Sun\\\' (on Sheba Chhachhi\\\'s art), in Adelina von Fuerstenberg ed., Urban Manners: 15 Contemporary Artists from India. Geneva: Art for the World & Milan: Hangar Bicocca, 2007.

Bernal, Martin. Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilisation. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Bharucha, Rustom. Another Asia: Rabindranath Tagore and Okakura Tenshin. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006.

CAMP, Wharfage. Sharjah: 9th Sharjah Biennale & Mumbai: CAMP, 2009.

Harrigan, Pat and Wardip-Fruin, Noah eds. Third Person: Authoring and Exploring Vast Narratives. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2009.

McEvilley, Thomas. The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. New York: Allworth Press, 2002: rpt. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2008.

Trojanow, Ilija & Hoskote, Ranjit. Kampfabsage. Munich: Random House/Blessing Verlag, 2007.