In the past decade the film genre of animated documentary has been the choice of an increasing number of film-makers. Originally, the genre has been mostly used when lacking actual photographed material of an event or when giving an account to abstract concepts . The 90's saw a change in the genre's approach with the production of several films regarding personal stories of individuals . Once again the lack of photographed material had most likely played part in the choice of animation but in these cases the focus on personal memory, rather than objective history, had contributed too to a choice which emphasizes the subjective.

Though the major shift in the genre both thematically and in number of productions has occurred during the 2000's, when addressing concrete events from recent history, of which photographed material is both available and well rooted in the collective memory. On those films animation is not used as an elegant outlet from a problematic situation but as a rational, idiomatic choice, and thus as one which carries a statement. The choice of animation over filmed material within the documentary genre should raise some eyebrows. After all the explicit objective of the documentary genre is to depict "things as they are" by using cinema transparently as a "window to the world". To give up on the most realistic aspect (photography) of the most realistic form of representation (cinema) seem to go directly against the very essence of the documentary enterprise. What is the ground from which such an unlikely fusion as anima-doco arises? And how do the films of this genre correspond with it? In the following lines I will try to give account to those questions with regards to several anima-doco films of recent times.

[b]Cinema V.S. Reality[/b]

As I see it, no answer to the first question will be full without addressing the continuous turbulence the concept of reality has suffered along the second half of the 20's century. The work of post-structuralist thinkers such as Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jean Baudrillard and others had caused a revolution in the approach taken by the arts to the representation of reality. With terms such as "Text" (Barthes), "Discourse" (Foucault) and "Simulacrum" (Baudrillard) those thinkers suggested a less rigid, less universally binding replacements to the naïve term – reality. As usual with major changes in the arts, this time too cinema was late to join the party, and finally did so in the 90's with the spring of film makers such as Pedro Almodovar, Quentin Tarantino, Jim Jarmusch and others who, along with more senior directors like Oliver Stone and Woody Allen brought to the realm of cinema the Post-modernist approach to reality. But it took at least 10 more years for documentary cinema to take part in the cinematic application of post-modernist ideas. Worth to mention, while the fiction cinema's approach is mostly based upon the motivation to de-real "reality", that is to mark the cinematic as a contextual, inter-textual entity, the approach most commonly taken by the anima-doco genre is exactly an opposite one, namely to mark the textual as the real. This opposition in the approaches taken correlates the basic fact that fiction cinema is rooted in the unreal while documentary cinema – in the real. This essential difference may also explain the delay taken by documentary cinema, compared with fiction cinema, in implementing post-modernism approach to reality. After all it is not as hard to accept the idea that "the texts around us are our world" as the idea that "the world around us is our text".

[b]Documenting "reality"[/b]

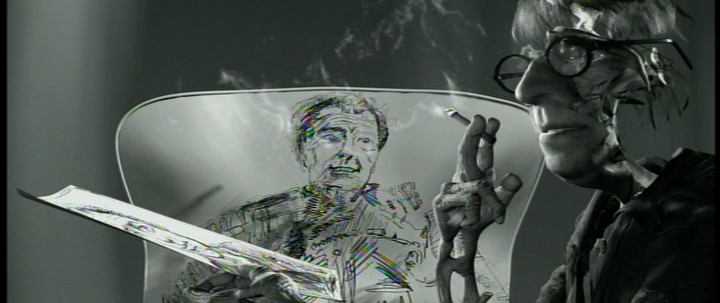

In the light of the above discussion I would like to argue that as a cinematic approach animated documentary indicates doubts regarding the naïve outlook on reality. How do films in this genre correspond to this argument? The 14 minutes Chris Landreth's Ryan (2004) animates an actual recorder interview, conducted by the film's director, with animator Ryan Larkin. The fact that the dialogue is authentic, along with the realistic style of animation chosen and the very rough depiction of actual Montreal's skid-row, puts this film in a very real context. This notion is intensified by the use of common formal tools of documentary cinema such as realistic ("field" like) camera movements and by the use of popular gestures of the genre such as the director's direct turn to the audience and his narration using voice over during the film. However, this realism is clashed with the very unrealistic world depicted. This is a world in which people walk and talk regularly with holes in their bodies, or only with the frontal surface of their head. In this world pointy spikes emerge out of bodies, hands pop out of heads and faceless beings walk the streets. The result of this clash may be the conclusion that Ryan's use of animation is merely as an expressionist tool to convey the power of emotions and the vividness of mental crises in the lives of individuals. In that case its fantasy world symbolizes a sort of a "dive in to the realm of the psych" and therefore the motivation of its documentation cannot exceed from this subjective realm in to the common objective reality. But I believe that Ryan should not be disposed of that easily. The film's formal style relies heavily on popular conventions of modernist cinema such as extensive use of fast editing, jump cuts, zoom activity and use of unconventional camera angles. Those conventions present notions of "filmed reality" . This cinematic language, when used in filmed cinema, usually marks the cinematic as a text, not as reality. But when it is used in an animated text the "already textual" copies the conventions of the "filmed that tries to mark itself as textual". This loop of realities puts us right in Baudrillard's "reality" of simulacrum. So Ryan does tell something about reality. If "reality" is realistically presented as a twisted fantasy world, and if there's no reality beyond "reality" then what we are left with are the worlds we create in our psych, with our fears or passions or like Ryan Larkin and Chris Landreth – with animated films.

But while in Ryan the doubts being raised against the common notion of reality are subtle, they are explicitly presented in Ari Folman's 2008 Waltz With Bashir. The film follows its maker's journey, through talks with friends, soldiers, therapist, Journalists and specialists, into his own memory from the 1982 Lebanon war. As in Ryan this film too uses modernist cinematic language. Limited camera angles, jump cuts, shoulder "news real" camera movement and foregrounding of the camera (for example, with a shot of a snack wrap that fly off and stick to the "camera lens"). Once again, those tactics, when used in an already "unreal" medium marks the film with a post-modernist attitude towards reality. The film also uses common convention of the documentary genre when in its later stages interviewees are seated in a studio in front of the camera, artificial lighting surrounds them and a blank background is set behind them. Text credits at the top of the frame tag their name and occupation, the interviewer is put off-screen and his questions too are "edited" off the film, so we only hear the answers. All are conventions of the documentary genre. The use of such explicit documentary conventions, along with the very realistic depiction of actual, some well known, interviewees, about well known actual events, leaves no doubt regarding the effort of the film to show reality as it is. Still all of this is presented using animation. Once again the obviously textual is doing its best to present itself not as reality, but as the common representations of reality. In Waltz With Bashir The representation becomes the source and the photographed the origin. Once again Baudrillard's world of simulacrum is our realm. But Waltz With Bashir does more than presenting the inaccessibility of the real. It also resonance the structure that choose one "reality" over another, a structure that creates collective and individual memories – full of holes and unsolved fantasies. Another film which places the political relevancy of the perception of reality through animated documentary is Brett Morgan's 2007 Chicago 10. The partially animated film describes the 1968 democratic national convention protest activity and reenacts the "Chicago 8" trial based on transcripts and rediscovered audio recordings. The trial reenactment plus several other scenes constitutes the animated part of the film while archive documentary footage fills its rest.

Right from the first minutes of the film we are thrown into the inter-textual, contextual perspective that will guide it trough out. The soundtrack choice of the song Wake Up by political rock band Rage against the machine in the opening of the film does not only mark the film as a political call against an oppressing regime but also recalls the film The Matrix and by that places the film in an inter-textual context. But more important – by recalling The Matrix it implies that "reality is not what it seems". The inter-textual context hovers over the entire film as it constantly refers to Haskell Wexler's 1969 Medium Cool which not only dealt with the exact same subject matter but also was noted for mixing documentary and fictional narratives in what might be referred to as the first post-modernist documentary film. But the main importance of Chicago 10 to my opinion lies in its insertion of the anima-doco into the symbolic core of truth – the court. The fact that all court activity is animated, along with the obvious stand taken by the film – that injustice was made in that trial, marks an attack on the way "truth", "reality" and "Justice" are interwoven by power structures. The decision to show the relation between those aspects in the form of animation implies the contingency of "Justice" and its ever engaging with perceptions of reality, which are concepts (as implied by The Matrix allusion) determined by power and control.