I will say a few words about how the art scene used to function in society by using the example of Zagreb in the 1960s. Yugoslavia was a member of the Non–Aligned Movement at the time, and supported the third way which was neither the Western type of capitalism nor the Eastern Bloc communism, with a specific economic system of so called self-management. In this in–between space, there was always a way out for culture.

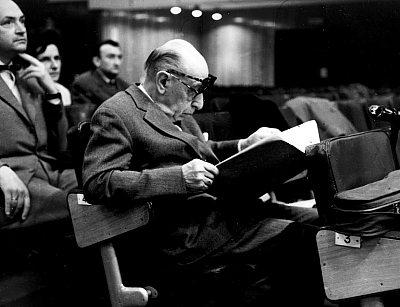

I will read a quote by the composer Milko Kelement, the founder of the International Avant–garde Festival of the Music Biennale to show how people in Yugoslavia unlike the East European countries tried not to be isolated from the rest of the world. On the contrary!

»In the middle of the 1950s I stayed in Darmstadt where I worked and studied at the famous Darmstadt School. This is where I met Penderecki for the first time. […] When I returned to Zagreb in 1959 I got the idea to organize the Biennale. I went to the then mayor of Zagreb, Mr Većeslav Holjevac. I told him that I would like to organize a big festival. He did not raise his head from the paperwork. It was only when I told him: »If you don’t let me organize the Biennale in Zagreb, I will do it in Belgrade«, that he looked at me as if I had jabbed him with a needle. »What do you want, what do you want!«, he started yelling. »I can give you a room full of dinars for that, but I cannot give you a single dollar.« I asked him how I was, then, supposed to bring the opera from Germany, the ballet from Russia or an orchestra from America. He replied: »Comrade, deal with it.« I exactly knew what I needed to do. I started negotiating with the Soviet Union. Yugoslavia was then like a turning point around which international politics was revolving. I went to Furceva, the Russian Minister of Culture at the time. When I told her about a growing influence of America and the West in Yugoslavia and how we in Zagreb needed the Leningrad Ballet and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, she immediately agreed. And I got it all for free.«

Then Kelemen went to the USA, to the State Department in Washington DC. There he held a series of discussions where he emphasised that Yugoslavia was under a major Russian influence and that the Russians were the first to register for the Zagreb Biennale, and how he wanted the Chicago Philharmonic Orchestra and the San Francisco Ballet to participate as well. This is how he got all what he wanted from the Americans.

»When I got the Russians and Americans, the rest was pretty easy. It is no wonder that they later called me the musical politician,«1 concludes Kelemen.

The Music Biennale was established in 1961, famous musicians and performers from the West and East came to Zagreb and this, at the time of the Cold War, was a rare occasion in other countries. In early sixties the Bolshoi Theatre performed alongside the Hamburg State Opera, Igor Stravinsky came to Zagreb, Mauricio Kagel, Luigi Nono, John Cage, Lukas Foss, Shostakovich, Witold Lutoslawski, Mstislav Rostropovich, Stockhausen, Bruno Maderna, Pierre Schaeffer and Olivier Messiaen, and many others and the whole generation of our composers of avant-garde music such as Ivo Malec, Milko Kelemen, Dubravko Detoni…

Hence, a series of important cultural events developed from the principle of »Comrade, deal with it«. Apart from the Music Biennale, I would mention just a few: international exhibitions of the New Tendencies (1961 – 1976), the Genre Film Festival (1963 – 1970) and the neo-avant-garde Group Gorgona (1959 – 1966). Seems to me - it is only owing to the fact that certain individuals »find their ways« that today we have a relevant history, despite of unfavourable economical conditions and an underdeveloped artistic system.

The first exhibition of (» New Tendencies «) (1961) was organized at the initiative of the Brazilian artist who lived in Germany, Almir Mavignier, who in cooperation with the curators of the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb came up with the idea for an exhibition that was to present the current situation of contemporary art (mainly geometrical abstract canon, actually neo–constructivist art). The exhibition including mainly international artists from the West including: Piero Manzoni, Group Zero, Manftedo Massironi, François Morellet, Dieter Roth, etc. In the second edition (1963) fifty-eight artists were presented such as: Getulio Alviani, Enrico Castellani, Enzo Mari, Henk Peeters, the GRAV Group, Julio Le Parc, , Gruppo T, Gianni Colomo… In the third edition (1965), the number of participants doubled again. The majority of works belonged to optical and kinetic art. For the first time artists from the USA and the East European countries took part: from the Soviet Union: Group Dviženije, then from EE Imre Bak, Zdeněk Sykóra, Miloš Urbásek. Almost half the contributions were of North American origin at the fourth (» New Tendencies «) (1969), mostly mathematicians, physicists, or engineers since the exhibition was about computer art. The fifth (» New Tendencies «) (1973) included conceptual art with a large number of American and Western and EE artists: (Štefan Bělohradský, Endre Tót, John Baldessari, Daniel Buren, and many others).

The Genre Film Festival (» GEFF «) (1963-1970) was founded by members of Kinoclub Zagreb (the Association of Amateur Film Makers) on the initiative of Mihovil Pansini. It promoted experimental film or anti–film, as they called it, and in just several years grew into an international event which presented in 1970 American underground film with sexuality as the main theme (the title was: »Sexuality as a possible way into new humanism«).

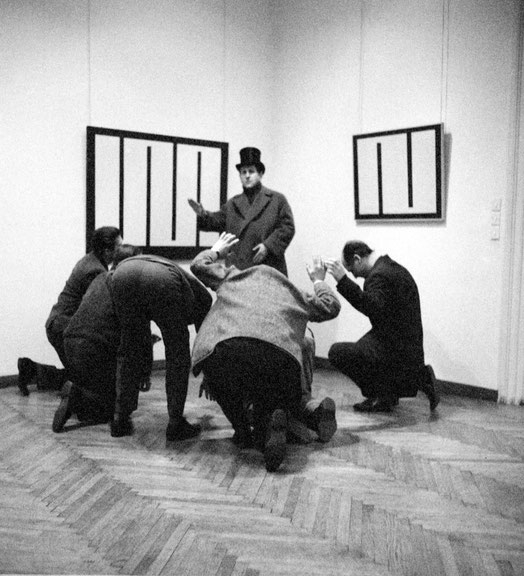

Gorgona group between 1959–1966 developed various forms of activities in which they broke with modernism that was regarded as a kind of official art in the former Yugoslavia. They proposed concepts, projects, led artistic actions, etc. The first forms of dematerialization of art are found in their works. Here are just several examples that I believe are well known today:

In 1962 in Zagreb Josip Vaništa, sent an invitation to fifty addresses culled from the address–book of Studio G. It said: »You are kindly invited to attend », without saying where or why they were invited. In this invitation card there was practically nothing material, only this text, a simple thought: invitation to/at Nothing. The statement makes use of a social convention, in order to caricature it and to function subversively in art. Inserting itself into the very structure of the way the gallery works, it criticises it from within. The work is entirely outside the pictorial tradition and opens up many questions about the gallery context. At the same time, it is a neo–Dada provocation that confuses, and a conceptual action that raises the base philosophical questions: what, where and why?

In 1964 in the work called »Painting«, instead of materialising it in paint, he wrote only a text describing what the »painting« looks like. Vaništa, who has always been congenial to immaterial sensibility, decided to substitute visual work of art for a verbal equivalent.

The group members had a special habit of exchanging literary quotations that expressed the state of mind of their »Gorgonian«community and that they wanted to share within members. They called them »thoughts for a month«. Quotations that Vaništa used to send his colleagues confirm his interest in Yves Klein, John Cage, Allan Kaprow, Allain Robbe-Grillet, Lao Tse, and others; among them, the quotations supporting the concept of emptiness occupy a significant place. While reading the »thoughts for the month« one can see how the group was connected with the international neoavant-garde.

Their activities cannot be interpreted as a belated reflection of Western art (which was how Eastern European art was usually interpreted), but as their inclusion into the artistic scene on equal terms. Their interconnectedness is, most of all, visible in the anti-magazine Gorgona published in Zagreb between 1961 and 1966 with participation of the members of Gorgona plus Victor Vasarely, Harold Pinter and Dieter Roth. Each number contained the work of only one artist. By affirming the awareness of artists for the medium in which their works appeared, Gorgona anticipated the artist’s book (the form that was yet to follow in 1970s). Anti–magazines by Piero Manzoni, Enzo Mari and many others were prepared but unfortunately never published. Vaništa exchanged letters with Fontana, Rauschenberg and others in relation to publication of Gorgona. He advertised the anti–magazine in the Dutch journal Null and his correspondence with Hans Sohm, Henk Peeters, the New York book dealer George Witterborn (through whom Gorgona reached MoMa), reveals the artist’s wish that Gorgona should reach the place where there is a true interest for it.

The »Gorgonians« developed almost all the elements of an artistic system. Their self–organization was on such a high level that at the time when it was almost impossible to run a private enterprise, they ran a gallery in the very heart of Zagreb. They also »managed with what they had« as mayor Holjevac said »dealt with it«. They found a loophole in the law: in other words, in a shop for picture frames, they rented a space and during 1962 and 1963 they organized exhibitions there (exhibitions of the members of the Studio G, Morellet, Dorazio, etc.). The members of Gorgona who were particularly active in organizing exhibitions were art historians-curators, such as Matko Meštrović, Radoslav Putar, Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos. It was owing to them that Gorgona got connected with the Gallery of Contemporary Art and the New Tendencies, which was visible in their programme. Other members of Gorgona were painters (Josip Vaništa, Julije Knifer, Marijan Jevšovar, Djuro Seder) sculptor (Ivan Kožarić) and an architect (Miljenko Horvat), and the group had »associate members« from various professions, such as music, theatre and film (Milko Kelemen (MB), Mihovil Pansini (GEFF), etc.) The strength of the group lies in its openness and connections with the domestic and international art scene. Vaništa said, they aspired, in a world filled with ideology, to normal behaviour, to a natural life«2.

How did the society perceive them?

All their activities were accompanied by very short articles in newspapers. But they did remain recorded! Once the main national newspapers referred to the work of Knifer’s Gorgona in the comics section (since the only content of the anti-magazine was meander in form of leporello). Publications of private editions were banned at the time as in other East European countries, which is why Vaništa was interrogated by the police. Fortunately, without serious consequences. Božo Bek, the director of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, helped him. In order to protect the »Gorgonians«, he described them to the police as »eccentrics«. The Gorgona Group was active on the margins of our society. Their influence, unlike that of writers and filmmakers, seemed harmless. As a result, the society tolerated them, but did not respect or support them.

How do we relate to these examples of important events today?

Today, there is still no meaningful cultural politics in Croatia, no »system of art«, no art market that would itself function as a stimulus... Is the rule »deal with it« still valid today and what are the consequences?

The Music Biennale – continuously held without interruption. It does not have the same influence on the cultural scene as in the 1960s when John Cage shifted the limits of art, but it is still a serious and respectable event.

Exhibitions of the New Tendencies were the starting point for the international collection of the Gallery of Contemporary Art, the only museum in the former Yugoslavia that collected international works of art. Works purchased at that time on NT are core of the collection. But – even though the current Museum of Contemporary Art held an abundance of records (letters, photo–documents, audio–recordings, etc.), it was not the institution holding the documents, which historicized this very important movement. A beautiful book on the New Tendencies was recently published by ZKM.

Regarding GEFF: The book on GEFF was published already in 1963, but no new studies have been published. The influence of GEFF was crucial for experimental film, anti–film and video. Today, there is a film festival called »25 frames per Second« which in a way continues with the tradition of GEFF. Our art historians still have not done a comparative research of the amateur and experimental film and history of visual art from the second half of the 20th century.

The activities of the Gorgona Group have not been identified by the Museum of Contemporary Art as a priority issue – the Gorgona archives held by Josip Vaništa is gradually dispersing and we have again failed to fulfil its historical task.

Too many things today as before depend on individual efforts and casual opportunities and this is certainly not the way how respectable art history should be structured.

1. http:// www.nacional.hr/clanak/33933/46-godina-poslije

2. Josip Vaništa, in Marija Gattin, Gorgona – Protocol of Submitting Thoughts, Museum of Contemporary Art. Zagreb, 2002, pg. 157.