The current wave of 3D cinema follows a series of earlier attempts of three-dimensional film screening. 3D films appeared as early as the 1950s, as a kind of gimmick which could not really fit within the established film industry due to their high costs of production and display, and the lack of a standardized format for the different segments of the entertainment business. Nonetheless, in the 1980s and '90s, 3D cinema had a worldwide revival driven by IMAX theaters and Disney themed-venues. 3D films became more and more successful throughout the 2000s, culminating in the unprecedented success of Avatar (James Cameron) in 2009. Yet the roots of 3D cinema’s development go much further into the past, in fact all the way back to the beginning of cinema, and even to pre-cinematic technologies such as the magic lantern and the phantasmagoria. This article will attempt a mapping of today’s risen genre/technology of 3D cinema as a transitional link between those proto cinematic forms and 3D cinema’s aspiration to break out of the limits of contemporary media towards a future technology of the virtual.

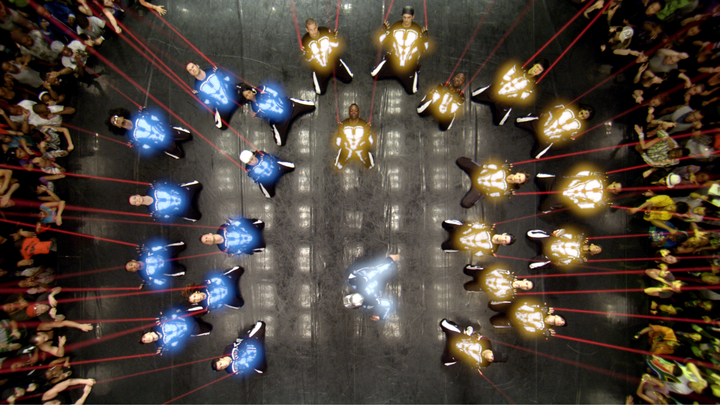

Regardless of any specific content or narrative, the uniqueness of 3D films, the reason we agree to pay extra fee to see them (or come to the cinema at all) is their effect: the feeling of depth and the sensation of watching objects “jump at you”. In this respect 3D cinema is a continuation of what Tom Gunning calls ‘cinema of attraction’.1 According to Gunning, the cinema of attractions characterized early cinema aesthetics, which directly assaulted the viewers’ senses by delivering visual shocks with images rushing towards an impact with the audience. While films such as Avatar contest the notion that 3D cinema today is a mere attraction, some kind of a cinematic rollercoaster, it is not accidental that many of the latest 3D films belong to what is considered “lower” genres such as horror and fantasy films, since these genres are dominated by spectacle which takes over the narrative. While many of 3D films are rich with narrative as well as spectacle, many others give the feeling that the narrative is just an excuse, a “time filler” in between spectacle sequences that give the real thrill of images rushing forward to meet their viewers. A film like Step Up 3D (Jon Chu, 2010), for instance, is constructed in a similar way to porno films. While the dance scenes demonstrate the genre’s new technology as dance maneuvers bulge out of the screen “into” the cinema in exciting, intensive ways, the two-dimensional narrative sequences, which look like a numbing TV soap opera, do not have any function but to fill up the time in between dance numbers. Piranha 3D (Alexandre Aja, 2010) acknowledges it quite directly with a porn director protagonist, while posing the viewers at the position of the deadly piranha fishes (sharing the same POV), hungry for the next gruesome spectacle scene.

One of Gunning’s prominent examples of attraction cinema, the Lumiere’s film L'Arrivée d'un Train à la Ciotat (1895), is famously connected with a myth about the naïve viewers of this film, which confused the image of the train rushing towards them with a real train, and fled in terror. Christian Metz describes this myth as a displacement of the contemporary viewer’s credulity onto a mythical childhood of the medium. The myth of those infantile early cinema spectators allows us to disavow our own belief in cinematic illusions.2 Although by different means, 3D cinema basically offers a very similar illusion of objects rushing toward us. It is therefore occupied with its own status as an attraction cinema and the supposed lack of contemplation on the part of its viewers. Final Destination 3D (David R. Ellis, 2009) is perhaps the best example of 3D as attraction cinema due to its motif of disasters, which in the 3D version (there were already three Final Destination films before) gives an almost haptic experience of encounter with the countless objects shooting directly towards the audience. In a reflective scene of a 3D film within the film (according to Gunning early attraction cinema also explicitly acknowledged its spectators), we hear someone shout “fuck you suckers” just before a horrible accident occurs, killing and burning all the spectators in the 3D cinema hall. As often the case with the Final Destination series, this scene was just a premonition, and the audience is eventually saved from the real disaster. Apparently the creators of the film felt some contempt for their audience, who pay money to see things being thrown at them, yet they could not really kill the audience, as those “suckers” are indeed paying customers. The double structure of this scene – an imaginary destruction which is followed by the “real” saved audience – points to the reception of 3D films as attraction cinema. According to Gunning, the audiences of L'Arrivée d'un Train à la Ciotat were not really naïve enough to confuse an image of a train with a real train rushing towards them, but were indeed thrilled by the illusion of the cinematic apparatus itself. As Gunning describes, in the earliest Lumiere exhibitions the films were initially presented as frozen unmoving images, projections of still photographs, and then - the image started to move. ‘Rather than mistaken the image for reality, the spectator is astonished by its transformation through the new illusion of projected motion. Far from credulity, it is the incredible nature of the illusion itself that renders the viewer speechless.’3 In a similar way, when a 3D image is moving towards us, we do not simultaneously turn back in fear, as the spectators are depicted in the Final Destination 3D cinema scene. Even when facing a scene which transforms the illusion into a real threat that can kill the viewers, we know we are still within the safety of the cinema. Spectators’ turning back in fear is a myth of 3D cinema, which both hides contempt for its audience, and a mythical belief in its own powers. Like the viewers of early cinema, we are not naïve, we do not believe that the three dimensional objects coming at us are real; it is the shift from two dimensions to three, the astonishment of this new technological illusion, which makes us excited. We know we will not be hurt by the objects springing at us, but we enjoy the sensation of the illusion of a real accident, the imaginary destruction of the limits of the screen.

Seemingly, the images of 3D cinema are no longer bound to the flatness of the screen, and like ghosts, can hover around the cinema hall. In this respect 3D cinema is a descendent of the phantasmagoria, the so-called ghost shows of late nineteenth-century Europe which produced “specters” through the use of magic lanterns. In darkness, with the screen itself invisible, images could be made to appear like fantastic luminous shapes, floating inexplicably in the air. Like the early cinema of attraction, the phantasmagoria mediated between rational and irrational imperatives. As Terry Castle writes, the producers of the phantasmagoria often claimed this entertainment to serve the cause of public enlightenment, warding off so-called apparitions by exposing them to be mere optical illusions.

Yet the pretence of pedagogy gave way when the show itself began. ‘Everything was done, quite shamelessly, to intensify the supernatural effect. Plunged in darkness and assailed by unearthly sounds, spectators were subjected to an eerie, estranging, and ultimately baffling spectral parade. The illusion was apparently so convincing that surprised audience members sometimes tried to fend off the moving “phantoms” with their hands or fled the room in terror.’4 In 3D cinema we encounter this ambiguous reality effect in many films which locate us at once in a rational, safe and familiar space on the one hand, and a fantasmatic, super-natural or virtual space on the other. Final Destination’s double structured scene of 3D cinema at once creates the irrational threat and the knowledge of safety, the knowledge it is just a film and the (ideal) feeling this might be more. This feeling concerns the 3D cinema function of the screen as a limit that signifies its own transgression. We are confined to observe the screen, yet this screen itself offers us a leap beyond.

Jean-Louis Baudry had pointed to the fact that although free to travel in their “mind’s eye”, spectators in the cinema are physically bound, like Plato’s prisoners of the cave, in a state of relative motor inhibition. The inhibited state of imprisonment in the cinematic space is a consequence of what Baudry distinguishes as ‘dispositif’, a subject positioning which is an ideological function in the Althusserian definition of ideology, that is, a state of mind produced through materially embodied social practices. The spectator’s regressive state is a consequence of the material positioning of her/his body in cinema: ‘the darkness of the movie theater, the relative passivity of the situation, the forced immobility of the cine-subject, and the effects which result from the projection of images, moving images, the cinematographic apparatus brings about a state of artificial regression’.5 Cinema frames the diegetic space, but also the spectator. This double bind appears in Rare Window (Alfred Hitchcock, 1954): James Stewart is peeping on the windows of neighbors from his home as a cinematic voyeur, yet his omnipotent gaze has a direct link with an inhibited state, his handicapped leg which confines his ability to move. Many reviews focused on Avatar’s colonial narrative (native aliens saved by the white American messiah…), yet this film is extremely interesting also from the perspective of the 3D medium itself, which like Rare Window, describes a handicapped protagonist that through a kind of cinematic technology can travel to other realms. The human body is perceived in Avater as artificial and partial, while the Navi aliens are perceived as the natural whole body (in symbiosis and harmony with nature). The paradox is that in order to become “natural” the film suggests we should leave our human bodies, a transformation achieved through technological means. Yet what the film perceives as natural is in fact virtual, an alternative world illuminated by unnatural phosphorous colors, where we can live a fantasy of perfection which our own bodies can never allow. It is the fantasy of 3D technology itself, which comes from the phantasmagoria past and projects towards a virtual future – to cross the limits of the frame and to move to other bodies and other worlds.

Tron: Legacy (Joseph Kosinski, 2010) presents us with the same fantasy: to cross the limits of the screen into the virtual. On the one hand the 3D remake of Tron appears in the film as a miracle, turning the 1980s fantasy into reality, as the spectator, just like the protagonist of the film, can experience the submergence in virtual space. Yet on the other hand Tron is aware that the viewer remains confined to his seat and bound to face the screen. Without movement, while the screen remains a reference point which cannot be avoided, the virtual space is indeed limited by the frame of the fixed perspective of the post Renaissance subject. This problem stems from the material limitations of contemporary cinema, its dispositif, which essentially did not change with 3D, but also – as can be seen in Tron and Avatar – it is a problem of the human body. It is the body which prevents the full passage to the virtual in Tron, and eventually the protagonist chooses “the real”, the rays of sun touching his physical body, the existence in flesh and blood. Yet paradoxically, this “real” is signified in the film by two dimensional images, a reduction of the three dimensions we perceive in our daily reality. Perhaps two dimensions at the age of three dimensional cinema marks the real as black and white sometime is used in color film. Or perhaps, as the philosopher Jean Baudrillard claimed, only the virtual can appear in three dimensions because the virtual became more real than reality itself. In any case, it is clear that both Tron and Avatar share a sense of failure. 3D cinema remains a missing link between its past and future, unable to fully release itself from the confines of the dispositif. Avatar’s technology can transport the protagonist’s mind, yet his handicapped, inhibited body stays behind. The spectators of Avatar can gaze into the three dimensional depths of other planets, but their bodies remain confined to the seats and their eyes still hang to the screen. The movement towards the disappearance of the screen and the eventual disappearance of the subject will be closely related. To fully cross into the virtual will mean the obliteration of both. Therefore, when the protagonist of Avatar completes a full passage into his avatar body the film ends – this is, for now, the limit of 3D cinema.

1 Tom Gunning The Cinema of Attraction: Early. Film, its Spectator, and the Avant-Garde.

2 Christian Metz, The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalyses and the Cinema

3 Tom Gunning, An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator.

4 Terry Castle, Phantasmagoria: Spectral Technology and the Metaphysics of Modern Reverie.

5 Jean-Louis Baudry, The apparatus: metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema.