Issue 3/2011 - Umbruch Arabien

Lost in Translation: Reading the Arab Spring from the Streets to the Arts

Similar to the media, the art world loves a good revolution. It provides fuel for a well-oiled machine, always on the lookout for the new, always searching to interpret or translate. In times of revolt, upheaval, global political and economic duress, the idea of »patience« is not a particularly popular one. In art as in diplomacy, it seems immediate action is the most adequate response to societal urgencies. Enter the Arab Spring.

Over he past few months political commentators have scrambled to make sense of the revolutionary fervour enveloping the Arab world. The perseverance, steadfastness, universalist demands, and sense of hopeful civic empowerment of the demonstrators in Tunisia and Egypt have inspired populations across the Arab world and beyond. Foreign affairs ministries have been left baffled – if not embarrassed – at how to cope or formulate policy in the context of these fluid events, and the local and international »knowledge economies« of academia and the cultural sector have been quick to react to – or appropriate as art historian Angela Harutyunyan argues – the revolution. Especially abroad, no week passes without panels, debates, and screenings parading throngs of experts dissecting the Arab Spring into bite-size categories deemed palatable for infotainment2.0 consumption. From the role of social media in these so-called facebook & twitter revolutions, to the liberating properties of art. While there is definitely a need for a thorough analysis of these political developments, many discursive events tend to perform a homogenising sweep of the region, which reduces the complex and hybrid nature of these uprisings. This is not unlike how contemporary art from the region is often lumped together as a series of easily packaged themes.

As spring turns into a violent and repressive summer in Libya, Bahrein, Yemen and Syria, and as the revolutionary shockwaves ebb away in Egypt, the momentum of the Arab Spring continues to pose questions of readability and representation. Rabab El-Mahdi, a political scientist at the American University in Cairo, contends that the narrative of the »Arab awakening« as told by the West, perpetuates orientalist binaries of East versus West and modernity versus tradition, as it excludes the bulk of the Egyptians who do not belong to the tech savvy English-speaking middle and upper class youth. There is a discrepancy between the composite demography of those who were demonstrating in the streets and squares of Egypt, and their representation and mediation. Between the act and its narration – or rather its translation – something gets lost. It seems that the American University in Cairo’s Center of Translation Studies has picked up on this issue with a symposium dubbed »Translating Revolution«. And so this inconclusive revolution has already morphed into an object of study, where the search for a semiotics and a vocabulary, as well as a classification system for the revolutionary imaginary and its imagery, are placed high on the agenda.

[b]To the streets[/b]

One could argue that art and artists are particularly well-placed to operate in murky semiotic waters. The reality is that many artists and art organisations in post-revolutionary – or rather trans-revolutionary – Egypt and Tunisia, are primarily concerned with re-positioning their practice vis-à-vis the novel situation. Here too issues like the documentation of the spirit and visual production of the revolution, concerns of representation, and art as a public practice and public discourse play a pivotal role. Workshops, panels, and performances have been organised at Alexandria’s Contemporary Arts Forum (ACAF), at the Townhouse Gallery, only a stone’s throw from Tahrir Square, and at Old Cairo’s art venue Darb1718. In March Darb1718 inaugurated an exhibition dubbed »The 25th January exhibition«, referencing the date the demonstrations commenced in Egypt; contributions showed artistic and other »creative« reactions to the revolution next to posters, banners, slogans and video and photographic footage coming straight from Tahrir. These types of initiatives have rather an archiving and commemorating value, than an artistic one.

The revolution was battled out on the streets of Egypt and Tunisia in a bid to reclaim public rights and a public voice, both in ideological and spatial terms. The most engaging and symbolic instances of participatory cultural commentary are at this stage to be found in those streets. Tunisian artist Faten Rouissi launched a call on facebook for artists, students and neighbours to use burned out cars in a vacant lot, the charred debris of the revolution, as an artistic canvas. The intervention, Art dans la rue - Art dans le quartier (Street Art - Art in the Neighborhood), turned into a collective public graffiti fest cum gesamtkunstwerk. In Egypt, where public space has always been rigidly policed, the Coalition of Independent Culture initiated Al Fan Midan (Art is a Square), an event which since May7th is organized every Saturday of the month, and transforms squares across Egypt into sites which embody the spirit of the revolution, and places for artistic expression; from puppet theatre for kids, to music concerts, performances and painting workshops . Graphic artist Ganzeer (Mohamed Fahmy) organized a »Mad Graffiti Weekend« wherein dozens of artists took to the Cairene streets of upscale Zamalek and the Downtown area, close to Tahrir. The idea was to stencil memorial murals of the revolution’s martyrs on Cairo’s walls, creating a permanent reminder that the streets belong to the people, and the price at which it came.

However, many fear that old ways die hard in Egypt, and that the newly gained window of freedom is in danger of closing again. Ahead of the protest on May 27th – the so-called 2nd Revolution - Ganzeer and two other artists, film director Aida El-Kashef, and musician Adel Rahman Amin (a.k.a. NadimX) were arrested for gluing activist stickers on Cairo’s walls. One of the stickers the authorities took offence to shows the naked torso of a man, tiny wings of liberty protruding from his head, with eyes blindfolded and mouth gagged. The text in Arabic reads: «New…The freedom mask/Greetings from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to the beloved people. Now available in the market for an unlimited time.« The poster, also printed on T-shirts worn by protesters, figures as an eerie omen and warns that there is still a long and steep road ahead to political reform, and that the population should not be pacified into submission.

[b]Plotting a Biennial[/b]

Amidst the din of popular protest in the region, the 10th Sharjah Biennial, titled befittingly Plot for a Biennial, opened on March 16th in the U.A.E. Though most of the works were commissioned well before the Tunisian and Egyptian regimes collapsed, traces and tensions that gauge a particular political climate are to be clearly detected. Curators Suzanne Cotter, Rasha Salti and Haig Aivazian dedicated the biennial to the winds of change in the region, but also expressed scepticism and reservation towards the role of art in turbulent times. They stressed the importance for art to reach the streets and reach out, without becoming outreach, a veiled warning to all cultural institutions capitalising on the revolution. In other words, they posed the thorny question of how and when art and politics relate to one another, and when that relation becomes skewed.

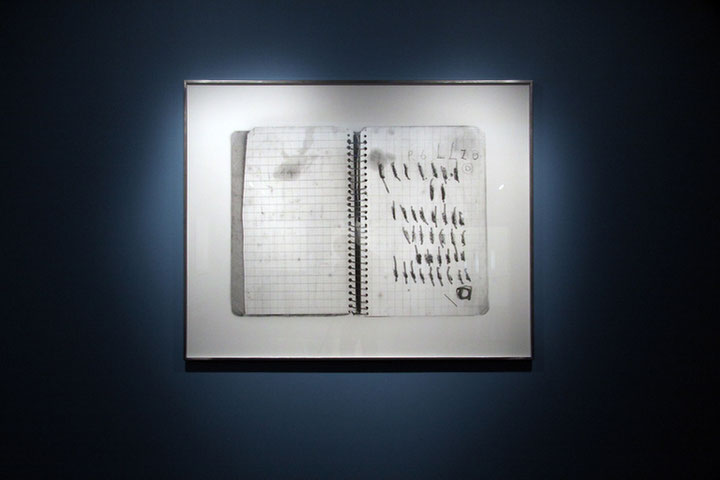

With over seventy artists participating in the biennial - many from the Middle East, North Africa and South East Asia – the conceptual framework of the biennial followed a set of motifs that can loosely be followed throughout the projects. The latter toys with deception, treason, devotion, affiliation and translation, the ingredients standard in any conspiracy, or in hindsight in any revolution. With a genuine focus on the artworks, rather than an overbearing curatorial thematics, this biennial spoke in different aesthetic and topical tongues, each plotting out their own scenario. Moroccan artist Yto Barrada follows up on the theme of translation in her series of photographs The Telephone Books (or the Recipe Books). Barrada’s illiterate grandmother reused recipe books as address books, wherein family telephone numbers are recorded as lines, as she could not read numbers. Each entry is accompanied by a drawing to identify the family member. Here something as generic as a phone number becomes a subjective document, an archive of memories. If the digits of the phone number blackbox information, then Barrada’s grandmother has cracked the code, and personalised it. The inventiveness of translating alphabetical illiteracy into a pictorial literacy also speaks of a self-sufficiency and autonomy from the margins.

Iranian painter Rokni Haerizadeh, who since 2009 lives in exile in Dubai together with his more notorious artist brother Ramin Haerizadeh (also included in this biennial), exhibited his series of multi-media paintings Fictionville (2010). The series dwell on Iran’s failed 2009 Green Revolution, which the artist experienced through broadcast media and the internet while residing in Dubai. Haerizadeh culls televised images of the Iranian riots from the TV screen, and turns them into violent fables by transforming the protagonists into animals: riot police become fanged monsters, demonstrators become sheep or feline creatures, politicians become pigs. Absurd and carnivalesque, the individuality of the actors in these scenes is reduced to the stereotypical role they perform: aggressor, victim, perpetrator, accomplice. In Haerizadeh’s hyper-mediated scenario no one is fully innocent; everyone seems part of the plot.

The difficulty of articulating a condition wedged between repressive stasis and dynamic upheaval is best exemplified in David Thorne and Julia Meltzer’s award-winning video Not a Matter of If but When, developed in collaboration with Syrian dancer, performer and filmmaker Rami Farah. Produced in 2006, after a particularly turbulent few years in Syria and neighbouring Lebanon, with events such as the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq el Hariri, Lebanon’s »Cedar Revolution, and the withdrawal of Syrian troops from Lebanon, the piece is an attempt to find meaning in a time when vocabulary has become depleted. In his non-verbal improvisations Rami Farah asks what sense we can make of convoluted notions such as war, peace, religion, justice, struggle and freedom, and how within this ideological clutter, the individual can eke out a position. The 32 minutes of the video are filmed in close-up on Farah. This framing seems deceivingly simple, but it emphasizes how the actor’s body flips roles from body politic to citizen body, and eventually shows that boundaries are blurry, unfixed and capricious. Not a Matter of If but When is a timely portrait, especially read in the light of the current situation in Syria.

The Sharjah Biennial was unfortunately marred three weeks after its opening by the unceremonious dismissal of Jack Persekian, the Biennials’ artistic director since 2005, over the »shameful content« of Algerian artist Mustapha Benfodil’s mixed media installation »Maportaliche / It Has No Importance«. Set in public space in Sharjah’s heritage area, the work draws on the violence in Algeria’s civil war and particularly on such aspects as religion and the rape of women as a strategy of intimidation. The official line is that the installation offended visitors, yet with the unrest in neighbouring Bahrein, and human rights activists increasingly being monitored and arrested in the U.A.E., one can wonder whether this is just another instance of showing who is boss. The art hub veneer of the U.A.E. is thus rendered pitifully thin.

[b]Pavilionism versus other Acts[/b]

This year’s 54th edition of the Venice Biennial includes more artists from the Arab world than ever before: the Egyptian Pavilion honours the work of Cairene media artist Ahmed Basiony, killed during the revolution, while Iraq joins the Biennial for the first time since 1976, with a water-based theme, including artists from the Iraqi diaspora, such as Adel Abidin, a 2007 Nordic Pavilion participant. Saudi Arabia debuts at the Biennial with a carefully crafted politically correct project by sisters Raja and Shadia Alem that draws on the Kaaba in Mecca and Marco Polo’s travels. Soft diplomacy – and marketing – at its best for sure, but perhaps not the most exciting art. The U.A.E.’s second stint at Venice, is in the capable hands of Turkish curator Vasif Kortun. Though impeccably installed, thematically, as well as in display, the exhibition feels too controlled. Especially Reem Al Ghait’s piece, which draws on her previous installations »Dubai: What’s Left of My Land« (2008) and »Dubai: What’s Left of Her Land« (2009), dealing with the rapid changes in urban development in Dubai, comes across as contained. Meanwhile, the Syrian Pavilion, unluckily titled »Evolution« received sharp words from certain corners of the Syrian art scene , for being curated by two Italian curators, and showcasing more European artists than Syrian ones.

Hence, the complexities of national sensitivities and politics become inextricably entangled in an art event like the Venice Biennial. In the case of Egypt and Iraq, national representation is tinged with a newly-won defiance, but we can wonder how the sub-text of the pavilions of Syria, Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. translate into the current moment. The pan-Arab show »Future of a Promise«, and the Mediterranean exhibition »The Mediterranean Approach«, both feature internationally established artists such as Mona Hatoum, Emily Jacir, Lara Baladi, Khalil Rabah, Yto Barrada and Zineb Sedira, as well as younger talents such as amongst others Ziad Antar and Yazan Khalili. If national representation is not the point to make here, then is it substituted by regionalism? Luckily the quality of the work undoes easy comparisons and categorizations. Still one has to wonder whether in these unsettled times it is possible to experience these pavilions and exhibitions without politics overwriting curatorial and artistic intentions.

Perhaps echoes of the Arab Spring do not lie primarily in the representational pomp and politics of an institution like the Venice Biennial, but are rather to be found in smaller and more spontaneous actions of solidarity, like Lebanese artist and playwright Rabih Mroué changing the name of his solo exhibition »I, the undersigned« to the iconic slogan of the revolution »The people are demanding« .