Issue 1/2012 - Net section

The Diaspora Strikes Back

Contemporary Israeli Music and the Search for Alternative Identities

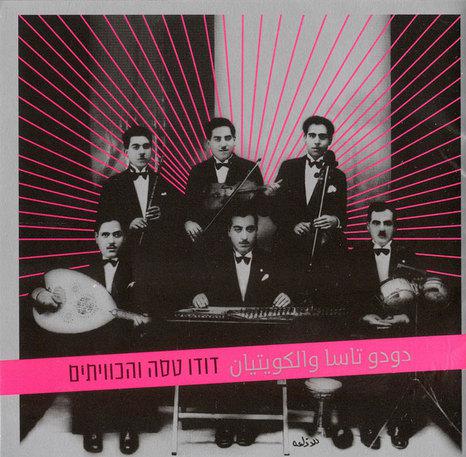

In 2011 Israeli musician Dudu Tassa released the album »Dudu Tassa and The Kuwaitis«. The album consists of modern interpretations of classical Iraqi music composed by two of the greatest musicians in the Arab world from the first half of the 20th century – The brothers Saleh and Daoud Al–Kuwaity (b. 1908 & 1910 respectively). Tassa happens to be Daoud Al–Kuwaity's grandson. This example, of a grandson returning to his grandparents' music in the Diaspora and giving it modern interpretation, is a symbolic example of a phenomenon I shall call »The Diaspora Strikes Back«. As I will argue, this is not a single phenomenon but an implicit movement which vibrates in Israeli marginal music of the past decade and which functions as a cultural symptom of the search for alternative models of identity in contemporary Israeli society.

During the Israeli state's first years of existence the need to tame and stabilize an incoherent clash of cultures had brought up a format of »Israeli Music« that was in accordance with a certain type of Israeli–Jewish identity. This came along with the elimination of other manifestations of Jewish identity. The search for those neglected identities, the deconstruction of formal models and the reconstruction of alternative ones is manifested through new sounds heard in Israeli popular music of the past decade.

In this article I would like to highlight the political implications carried by the search for new models of Israeli identity through sound and lyrics. In order to understand the impact of this current in Israeli popular music one must have at least a brief overview of the history of Israeli society and the place of music in its identity construction.

In Zionist history it is common to divide waves of Jewish immigrants to Palestine into those ranging from 1880 to 1948 – before the constitution of the Israeli state, and to those following the Israeli independence. Every period is further divided into groups, each characterized by its people's origin, socio–economic profile, ideology, cultural heritage, motivation and historical context. While the pre–state immigrations manifested a huge diversity of origins, bringing people from Russia, Poland, Romania, Germany, Czechoslovakia, the Baltic states, the Balkan countries, Turkey, Bukhara, Yemen, Iraq, Syria, Morocco, Algeria and Egypt among others; the massive immigrations of the 1950's were unprecedented in volume (the state population had doubled within 18 months) and, as it consisted mostly of Holocaust survivors, refugees from Muslim countries and entire communities of Iraqi and Moroccan Jews, was alien to the now–veteran settlement in worldview, cultural practices and ethos of Zionism, which in turn alienated the newcomers as they did not match the heroic, self–sufficient, young, Hebrew speaking, European looking model of the »Sabra« they have praised.

This extreme multicultural diversity along with the need to re–educate newcomers into Zionist hegemony forced unification and the »Tower of Babel« must have been homogenized. And so aspects of specific Diasporic cultures were repressed in favor of a model of the »new born Jew in the land of Israel«. That included first and foremost the language: Hebrew was the language to be spoken in Israel and all local Diasporic languages such as Yiddish, Ladino, Russian, German, Yemeni or other dialects of Arabic spoken by Jews should have not been commonly used.

In fact any aspect reminiscent of a specific Diasporic culture was not in line with the idea of building a new unifying model of Jewish identity. This new Jew is to be entirely »from Israel«, and as his Hebrew should be clean of any Diasporic accent so should his cultural expressions – including music – avoid any trace of Diasporic past.

Thus Israeli popular music of the state's first years was generally influenced by Russian folk and workers songs, Tango, French and Italian Chanson, Jazz, cabaret and Hollywood–style orchestral ballads. Many of these songs were lightly orientalised, to such an extent that they do express the new Jew's relation to their land in the heart of the Middle–East, but not to the extent that they irritate the ear of the European–Jew, or that they will express a specific Diasporic origin. Ironically, by avoiding any Diasporic Jewish characteristics the »Israeli music« ended up a mash of western musical styles combined with a mash of unspecified oriental elements, of which little had to do with actual Jewish culture.

This model, which has been thriving throughout the 50's and 60's, has been modified by newer generations of Israeli musicians, however those modifications were directed towards western rock–music on one hand and towards pop–music mixture of Middle–Eastern musical traditions known as »Mediterranean« or »Mizrahi« music on the other. None of these directions have challenged the exclusion of specific Diasporic traditions from the Israeli ear. While the inclination towards western rock suggested a search for an alternative identity across the ocean, the »Mediterranean« direction suggested an all inclusive ethnic identity through sound that, just like its predecessor, was European–ear »friendly« and implied no specified Diasporic tradition. A true change in this manner came only in the past decade.

I opened this article with Dudu Tassa's modern interpretation of his grandparent's Iraqi music and with the claim that Tassa makes one example in a movement of revitalization and reinterpretation of the Diasporic musical traditions. Hereinafter I will give a short account of various acts in contemporary Israeli popular music which take part in this movement.

»Ravid Kahalani's Yemen Blues« fuses traditional Yemenite songs with Blues harmonies, funk grooves and Jazzy improvisations. Similar to the impact of Tassa's production, which inserts Arabic lyrics, instrumentations and harmonies into the heart of contemporary Israeli pop scene and thus reveals the repressed of Israeli culture; the foreign sounds of Yemenite musical scales and Lyrics brought straight into the yuppie sound of funky light jazz creates defamiliarisation of the common Jewish–Israeli identity and reveals its silenced complexity.

»Oy Division« plays traditional Klezmer music, influenced by Yiddish cabaret and sung in Yiddish combined with a punk rock attitude. The use of Yiddish, a language apprehended in Israeli hegemony as »a dead language« and associated with the old and with the Holocaust is used here to reveal yet another culture repressed by the Israeli establishment.

»Habiluim«, although singing in Hebrew, manifest the influence of Yiddish culture and music combined with contemporary punk rhythms. The band is a unique example of a post–modern musical act. The use of hyper–genres, pastiche, musical, lyrical and cultural quotations and recontextualisations reveals the political mechanism of light entertainment and the texuality and contextuality of cultural products while the outfit of a Punk–Yiddish band carries a similar impact to that of »Oy Division«.

»Shmemel« is another band which incorporates Eastern–European Jewish traditions into a contemporary outfit of funk–rock and disco–dance. Even though the band is far from being explicitly political and mostly displays nonsense lyrics and a carefree attitude, its use of Yiddish traditions in regards to »fun music« makes a subversive act against common associations of Eastern–European traditions with Pogroms, anti–Semitism and grief.

»Orphaned Land« creates a blend of folk and classical Arabic music with heavy–metal aesthetics and incorporates those into a lyrical and conceptual world inspired by The Bible, The Quran and mystical and occult branches of both Judaism and Islam. This fusion of ancient Judaism and Islam concepts into a spiritual and musical oneness implies the mutual base and intrinsic harmony of the two religions that are grasped as oppositions in Israeli common thought.

With perhaps the exception of »Orphaned Land« (which resonate a mythical past instead of a geographic Diaspora) the root of these musical acts' political impact lies in their focus on a specified Diasporic origin, as opposed to various ethnic influences common to »world fusion« acts. This Diasporic choice is usually in accordance with the musician's actual ethnic roots, a fact that correlates the search for identity.

Another necessary character of these acts is the fusion of the Diasporic origin with a modern musical expression, be it jazz, funk, punk, heavy–metal or dance. This differentiates those musicians from their Diasporic past, puts them in a local and modern context and defines their search not as a simple return to the grandparents generation but as a search for a new identity, which is built upon, reflects and respects its past instead of erasing it.

As this musical movement implies a maturing society which is less afraid seeing itself fragmentary and finds diversity and polyphony as symptoms of its harmony; one can only wish that these kind of social and cultural expressions will turn from a marginal into a dominant aspect of Israeli music and culture.