Issue 1/2012 - Net section

Post-fake as game of projection

The phenomenon »Ursula Bogner« and the publication »SONNE = BLACK BOX«

»It is nearly unbelievable that my mother, Ursula Bogner, had remained unknown to Jan Jelinek till now. And Jelinek’s biography seems just as unbelievable, but also just as everyday, as hers. It was in a plane on the way to Vilnius that I made Jelinek’s acquaintance; he said he was on a concert tour. After preliminary small talk, we soon began to talk about how he, like my mother, who died in 1994, also played synthesisers, but not, as she did, privately, in the specially equipped music room of our detached house in Berlin, but in a specially equipped studio in Berlin. Unlike in the case of my mother, his surroundings take a great interest; music is perceived as one of his many eccentric activities. This is astonishing, as, on the surface, Jan Jelinek’s life is thoroughly bourgeois: studied, father, newly furnished old flat in Prenzlauer Berg. This makes his obsession with electronic music seem all the more bizarre: an obsession that, happily, drove him to set up his own studio for experimenting and recording. The bare facts of Jelinek’s biography are quickly told: born in Bad Hersfeld in 1971, he moved to East Berlin in the 1990s to study philosophy and sociology. While still a student, around 1994, he started producing and publishing electronic music, some of it under his real name, some as >Farben<, some as >Gramm< and most recently as …«

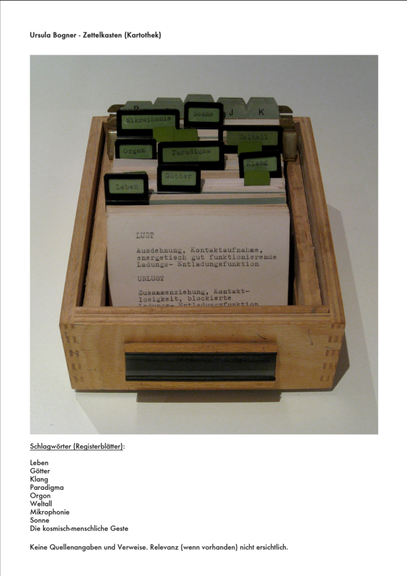

»Ursula Bogner« can be described first and foremost as an open principle for which music serves as a messenger substance. From the outset, this name, which first appeared in 2008 with »her« posthumous »Recordings 1969-1988«, containing 17 pieces, on the Faitiche label of the Berlin musician Jan Jelinek, provided the best possible basis for a successful, yet obvious, deception, with its combination of cosiness and fashionableness. Since then, there have been two exhibitions with scores, sketches, notes in card index style and scientific photographs from Bogner’s photo album (»Pluto hat einen Mond«, 2009/10 at the Laura Mars Grp. in Berlin, »Mélodie: toujours l’art des autres«, 2011 at CEAAC in Strasbourg) including a vinyl single. Now, a new production has appeared bearing Bogner’s name; it remains to be seen whether it is a finishing or a starting point. For the book »Ursula Bogner – SONNE = BLACK BOX«1 and the accompanying audio CD (or limited vinyl edition) with 15 titles, issued by Maas Media in 2011, already look back at the history of the reception of Jelinek’s invented figure (book), while also presenting new material (CD) that adds new facets to Bogner’s artistic biography, but dissociates itself from Jelinek’s authorship with regard to the audio production as well.

The German-English, 126-page book with contributions by Momus, Kiwi Menrath, Jürgen Fischer, Bettina Klein, Tim Tetzner, Andrew Pekler, an introduction by Jelinek and numerous photographs, drawings and composition sketches by Bogner, which, for the most part, already featured in the two exhibitions, interrogates strategies of a »post-fake« (probably done here for the first time) based on the figure of Bogner. According to Kiwi Menrath, »post-fake strategies […] [aim] to inspire critical reconstructions rather than carry them out themselves« – something that could be described as the pseudonymisation of artistic order.

In this sense, the account of the meeting on the plane to Vilnius at the beginning, described from the point of view of Sebastian Bogner and not, as in the »original«,2 from the point of view of Jan Jelinek, functions as a kind of test: a test of whether, in accordance with the same logic, the figure of Jan Jelinek might not be based, in an inspiring reversal, on a »post-fake« of the musician Ursula Bogner – and what this would say about producer subjects. In fact, according to the original text for »Recordings 1969-1988«, which was copied many times in the internet as well as being included in the book, it was Jelinek himself who met Bogner’s son on the plane and pumped him for information about the work of his mother, still unknown as a musician, which gave rise to the idea of rescuing her pieces from oblivion and presenting them to the public in edited form. The data on »Ursula Bogner« provided by Jelinek, however, is so obviously strange and so strangely obviously chosen that it is a matter of surprise that some critics of »Recordings« did not mention the fake as such, apparently uncertain of its programmatic extent: born in Dortmund in 1946, Bogner, a pharmacist working for the Berlin company Schering and »wife, mother, replete with detached house«, is reported to have taken a private interest in the activities of the Studio for Electronic Music in Cologne, attended seminars by Herbert Eimert, been a fan of musique concrète and have later shared »with her children a love of English New Wave pop«. In addition, she is reported to have had a long-lasting interest in Wilhelm Reich’s orgonomy. But what is more important is that all these fetishes were allegedly channelled into a wealth of musical and graphic works that were created over the period of 20 years – unnoticed by the public owing to Bogner’s reserved character – and that were now to be saved little by little from tapes and edited. In other words: who, if he, like Jelinek, grew up in a West Germany in which women born in the 1940s frequently were called Ursula, but usually did not hold the above-described preferences in this combination, would not have liked to be Sebastian Bogner? The charm of the project lies in this game of projection involving the (here) typically male producer subject, but also in the artificially, enigmatically produced music of Bogner herself, which, on the purely instrumental »Recordings 1969-1988«, still reveals rather Jelinek-esque funk echoes. »SONNE = BLACK BOX«, in contrast, has a kind of airy-fairy, cosmic quality and, in addition to tape manipulations, often presents Ursula Bogner’s modulated voice (vocals: »Ist denn die Sonne eine Blackbox?« (»Is the Sun a Blackbox?«); »Ob man die Nacht abschaffen kann?« (»Can the Night Be Abolished?«)), for which Andrew Pekler, who appears with Jelinek in live improvisations of Bogner material, is (not) responsible.

The figure of Ursula Bogner purports to fulfil an emancipatory, deferred promise, to unexpectedly close a gap, for the »FRG«, which was hopelessly behind the times in the way of pop music. It does this by adding a »better half« to the history of electronic or electro-acoustic music in the West German post-war era, which, unlike in England (Daphne Oram), France (Eliane Radique) or the USA (Pauline Oliveros), was always a male era (according to Momus, Bogner is Jelinek »in drag«). On »SONNE = BLACK BOX«, a bridge is created between sound cultures in Cologne (Studio for Electronic Music) and Paris (GRMC/GRM) using Bogner’s voice, historicistically distorted and mostly speaking or singing about cosmic topoi. In the process, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s »Gesang der Jünglinge« is cited (Bogner: »Der Chor der Oktaven« (»The Choir of Octaves«)) and its use of voices casually adapted, one could say, from serious to popular music – which leads to an imagined version of female electronic techno-pop in Germany parallel to the early work of Kraftwerk. In this way, the zeitgeist commentary »Ursula Bogner« presents the most gallant and smoothest »model of stultification« (Jelinek) that the retromania in the FRG can currently produce.

Translated by Timothy Jones

1 http://www.maasmedia.net/43verlagsprogramm-bogner-blackbox.htm

2 Vgl. http://www.faitiche.de/index.php?article_id=7