These last years, art's fascination with philosophy attained dizzying heights: philosophers such as Jacques Rancière and Boris Groys routinely take the floor at art fairs and biennials while a flurry of exhibitions mull over art's relationship to philosophy or the two disciplines' shared interest in concepts such as autonomy and truth. Equally flagrant is the art world's growing predilection for the philosophies known as »Speculative Realism«. Catapulted to notoriety by its rapid expansion in the blogosphere, SR not only questions established philosophical methods of dissemination, but is also helping to usher in a paradigm shift in contemporary art – from the Duchampian privileging of the viewer who apprehends and thereby completes the artwork, to a disturbingly non–anthropocentric object–oriented aesthetics.

Held at Goldsmiths College, London in 2007, the first Speculative Realism conference presented four philosophers united in their opposition to correlationism, the theory that we only have access to things as they appear to us, and not to things in themselves. In its place, SR offers up a mind–independent world indifferent to humans, with each philosopher adopting his own idiosyncratic approach: Quentin Meillassoux uses the term ›arche–fossil‹ to evoke the existence of a reality »anterior to terrestrial life«1, while Graham Harman emphasizes the importance of the object and has elaborated a system »which takes ‘›things‹ to be central to existence, and which classes humans as just one of those things.«2

Just as these philosophies crystallized around opposition to correlationism, so are the artists, critics and curators whose practice intersects with SR, united in their resistance to the relational, and in particular the so–called aesthetics of the fragment: the impulse to establish connections between isolated objects and occurrences as if they were part of a whole. Art historian Ida Soulard, artist and educator Sam Basu and curator Tom Trevatt were invited to discuss the implications of such a position at a symposium held last November at the Parisian project space Rosascape. In her paper, Ida Soulard emphasizes that SR is neither a movement nor a method. It is rather an open–ended field of research, a mental gymnastics that erodes the centrality of the human subject fundamental to Western philosophy, while giving access to a world without humans that was hitherto the domain of science. As she points out, this world is marked by developments in neuroscience, quantum mechanics and topology, and art should not be excluded from it. In his presentation, Sam Basu expresses support for educational projects that seek to displace the centrality of the individual artist, advocating instead collective non–hierarchical projects. Meanwhile, Tom Trevatt contests prevalent modes of exhibition–making, in which the artworks are signifiers for the curator's ideas, and their objective reality is passed over. Such an object–oriented approach may resonate with Graham Harman's theories, however as Trevatt emphasizes in his presentation, his aim is not to contribute to philosophical discourse but rather to show that art is well–placed to engage with the issues addressed by SR. The participants in the symposium have plans for a journal for artistic research and a follow–up conference designed to concretize the implications of speculative realist ideas for artistic and curatorial practices. Scheduled to take place in Treignac, France in September 2011, the conference will be complemented by workshops, performances and an exhibition.

The seminar at Rosascape took place in conjunction with an exhibition by the artist Fabien Giraud which touched on these questions, among other themes. Giraud discovered Meillassoux's writings while working on the show at Rosascape and was struck by the commonalities between the philosopher's conception of a world without humans and his own approach. As he puts it: »The connection between my work and speculative realism is that the pieces I create allude to a reality beyond the framework of human existence.«3 His exhibition is constructed around »Metaxu«, 2011, the script of a dialogue between himself and curator Vincent Normand that examines the sweeping changes wrought by the advent of modernity. Giraud further suggests that now that modernity has drawn to a close, art could revert to its pre–modern state and its original Greek name ›techne‹. The passage from the historical and aesthetic references of modernity to the physicality and materiality associated with the pre–modern is exemplified by such works as a rough–hewn lump of granite, and a sheet of paper stiffened by the application of successive layers of resin and charred wood – which evoke the elemental forces of prehuman times. Like the title of the show, which translates as »Death that Seizes Life (The House of the Outside)«, these works can be interpreted as references to a remote world untainted by human thought.

Although SR's counter–intuitive theses and dismissive attitude towards humanity in general have their detractors, for its supporters in the art world, the mental gymnastics it imposes are part of its appeal. As against relational aesthetics' reductive simplification of art to the relationship between the object and the viewer, curator and co–author of »Metaxu« Vincent Normand seeks to open the artwork up to multiple references and interpretations. His curatorial practice eschews restrictive organizational principles, emphasizing instead the richness of the individual work and thereby echoing the theses of SR. However as he remarks, »SR is not the starting–point for my curatorial practice, but rather a set of ideas that confirm my conjectures.«4

Such an object–oriented approach has important consequences, for if objects have an existence beyond our perception of them, they might well – like the weather – engage with us in ways of which we are not necessarily aware. »The Speculative Realists want to do away with the privilege of the human as the main point of access and acting in the world. This means assuming that there will be relations we enter into [unbeknown to us], and also things entering into relations with each other without [our] knowing it,«5 states Kristoffer Gansing, artistic director of the media art festival transmediale. Indeed, for Graham Harman, one of the key–note speakers at transmediale 2012, the relationships objects have with each other are as pivotal as the interactions between people and things. As Gansing comments: »This would obviously challenge [the privileging of human] intentionality, affecting what can be art or an aesthetic object, and prompting us to reflect on strange non–human aesthetics and the potential of animal art.«6

For Harman, there are also important connections between SR and media art: »The word ›media‹, of course, is the plural of ›medium‹. Everything that we explicitly perceive occurs amidst some background medium, and that background is more determinative for our experience than any of the contents of consciousness on which we are focused,« he remarks. »This was the key point driving the work of Marshall McLuhan, [...]We pay attention to television programs and words on the page, but it is harder for us to be aware of the effects on us of television as a medium, or of books as a medium [...] The background medium of all perception and speech is one of the dominant themes of my work.«7 In his presentation at transmediale, Harman questions another key constituent of contemporary thought, holism: »For decades, it was an automatically progressive intellectual move to speak out against isolated entities and in favor of holistic interconnection. In my opinion, holism has become the new cliché, and it's time to explore the extent to which objects ›are not‹interrelated.«8

Certain musicians and composers are exploring similar ground. In Manfred Werder's score »stück 1998«, 160 000 time units, each made up of 6 seconds of sound followed by 6 seconds of silence, extend over a duration of 533 hours and 20 minutes. The gap between the sounds is such that they do not form a language but are perceived as isolated occurrences, thereby paralleling Harman's anti–relational stance. High and low frequencies are also of interest to Werder, in that they transcend the realm of human hearing. They also affect us even when they are inaudible, demonstrating that our feelings and sensations are shaped by phenomena of which we are largely unaware. For Werder, the capacity of inaudible sound to impinge on our thoughts and sensations is mirrored in a sentence from philosopher Ray Brassier's »Nihil Unbound« : »It is no longer thought that determines the object, whether through representation or intuition, but rather the object that seizes thought and forces it to think it, or better, ›according‹ to it.«9

However, music cannot always do justice to the unfettered abstraction of SR–associated concepts, as Florian Hecker discovered when he composed »Speculative Solution«, a piece about Quentin Meillassoux's concept of hyperchaos. For a musical composition is finite, whereas hyperchaos relates to the infinite nature of the universe. The latter term also refers to real disorder, whereas the randomness found in certain kinds of contemporary music is merely another form of order subject to mathematical laws.10

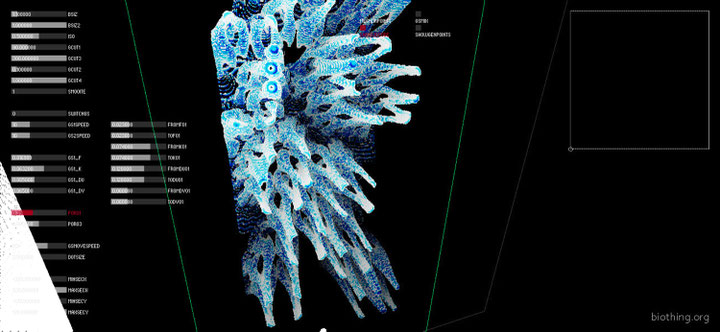

Radical and infinitely extensible, these tendencies, and in particular non–holistic thinking, the privileging of the object and the attribution of agency to material entities, are surfacing in disciplines beyond music and visual art. This year, the symposium »Objects in Performance« surveyed recent research into object–invested experimental dance and performance. Meanwhile, architect Alisa Andrasek is engaging with design from the perspective of material agency and the physics of matter, just as the research of mathematician Fernando Zalamea is eschewing the principle of total holism. As media artist Christopher Salter, who is himself working on a book on material agency in the context of art, comments: »The term ›speculative realism‹ has become a kind of catch–all phrase to describe what I see as a current obsession, not only in media art but also philosophy, cultural studies, political science, science studies and even the most human–centred disciplines like sociology and anthropology, with the ›nonhuman‹ or things, objects, processes that lie beyond human grasp....The general critique of anthropocentrism is important because after the last few years of such complete and utter social–technical disasters like Fukushima, the financial collapse and ecological catastrophe, [it implies] that perhaps our human–centred vision of the world is problematic.«11

What then, of art's relation to philosophy? For philosopher Robin Mackay, one of the most noteworthy functions of art with respect to philosophy is »to dramatise concepts so they can be ›felt‹.«12 In the case of speculative realism, however, art is not illustrating or expanding on philosophical concepts but itself contributing to the debate.

1 Quentin Meillassoux, »After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency«, transl. by Ray Brassier, Continuum. London and New York 2008, p.10-

2 From the introduction to “› ‹Graham Harman interviewed”, »Dialogica Fantastica«, http://dialogicafantastica.wordpress.com/2011/03/06/graham–harman–interviewed/

3 Fabien Giraud, in an e–mail interview with the author, January 2012.

4 Vincent Normand, in an interview with the author, January 2012.

5 Kristoffer Gansing, in an e–mail interview with the author, January 2012.

6 ›Ibid‹

7 Graham Harman, in an e–mail interview with the author, January 2012.

8 ›Ibid‹

9 Ray Brassier, »Nihil Unbound : Enlightenment and Extinction«, Palgrave Macmillan.New York 2007, p.149.

10 see http://www.grahamfoundation.org/public_events/3904–florian–hecker

11 Christopher Salter, in an e–mail interview with the author, January 2012.

12 Robin Mackay, in ayp.unia.es/dmdocuments/public_doc05b.pdf, p. 23.