Issue 3/2012 - Art of Angry

The reprimanded land

Increasing discontent and protest is bubbling up in the Israeli art scene – an on-the-spot investigation

Tel Aviv, late March. The Tel Aviv Art Year is trying to show this previously isolated art location in the best light. A long weekend aims to attract visitors with a 24-hour art marathon in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, recently expanded with a 35-million-Euro extension. A conference seeks to encourage investment in the Israeli art market, which has started to awaken from its slumber over the last few years; a dance event, concerts and many more events are promised. At the ticket office in the museum though there is no detailed information about what has been announced as the highlight of the year. Visitors are told to consult the – equally uninformative – website.

Out in the streets of the city: a graffiti with blue block-capital letters on an unplastered concrete wall, proclaiming »Isreal?«. As a matter of fact, references to the allegedly illusionary sensibility of the people of Tel Aviv now forms part of the standard repertoire of about half the travelogues that appear. The city is described as a bubble, as it was dubbed in a romantic film of the same name from 2006. Travel reporters emphasise the hedonistic lifestyles of the city’s inhabitants, who reportedly are permanently suppressing an awareness of reality, whilst the local populace in border cities such as Ashdot routinely has to crawl into air raid cellars whilst the soldiers enjoying a free weekend in Tel Aviv find themselves when they’re back in their everyday lives in the West Bank, the barrels of their guns protruding resolutely ahead of them, once again looking into the faces of Palestinians who perceive them primarily as occupiers and oppressors.

Yet this normalisation of a state of emergency, familiar from other crisis-stricken regions such as Bosnia, does not mean that there is no awareness of Israel’s complicated position and the political distortions in the country. On the contrary: around 700,000 people, around ten per cent of the population, took to the streets of Israel at the peak of what were known as the tent-city protests in early September 2011 – with an estimated 500,000 protesters in Tel Aviv, a city that only has a population of around 400,000. The protests, initially directed at an economic problem, namely the astronomical increases in real estate and rental prices in Tel Aviv, soon spread and encompassed a broader range of issues. They created links between the concerns of the »silent majority« of the Jewish Israeli middle class and the desire for a comprehensive democratisation of society; key issues in this context include conflicts within the Jewish population between the left and right, and between the secular and religious/Orthodox camps, the question of the formation of an elite made up of Jews from a European background and the marginalisation of Jews from the Arab world, the former Soviet Union or Africa, as well as the contradictions in the state’s self-image, for Israel views itself as Jewish and democratic but at the same time also encompasses non-Jewish, above all Palestinian citizens, and keeps the territories of non-Israeli Palestinians under occupation.

Tel Aviv-based artist Yochai Avrahami therefore takes the view that all the talk of the apolitical bubble in his city is a cliché. At the same time, he point out the fragmentary and divided nature of an emancipatory consciousness within the protest movement. »In Israel you can be on the left and be politically active to combat the exacerbation of the redistribution of resources away from the lower strata of society to its upper strata, yet simultaneously shrug your shoulders when it comes to proposals to resolve the Palestine conflict. And vice-versa.« In his projects Avrahami aims to condense historical research in objects that are taken from the real world yet charged with new meanings through media transposition and aesthetic distancing. In his video installation »Rocks Ahead« (2006–2008) it was sculptures made up of replicas of rubbish from politically sensitive places such as the Kalandia checkpoint in East Jerusalem or a Palestinian refugee camp, which, after a media-based transformation, is transformed into filmed settings for prehistoric animals that appear to have been brought back to life. In 2010 Avrahami showed his Installation »Uzi« in the Center of Contemporary Art (CAA) in Tel Aviv. At its centre was an exemplar of the famous star of the arms export trade, invented by Uzi Gal, who was born in Weimar. Avrahami superimposed the history of this submachine gun, which was introduced into the Israeli army in 1956, onto the Bauhaus architecture that is so widespread in Tel Aviv and that has its roots, inter alia, in Weimar, and on this basis created a complex narrative about the Uzi factory in Tel Aviv, which was abandoned in 1995 and is sometimes populated by the homeless nowadays, also addressing militant kibbutzim, Zionist ideology and echoes of militarisation in Israel and the Gaza Strip today.

Like many of the artists from Israel who are considered to be politicised, Avrahami displays a mix of scepticism and distance vis-à-vis representative domestic art institutions such as the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. In 2011, in conjunction with Doron Tavori, he organised a two-day lecture programme held at the Israeli Center for Digital Art in Holon in the context of the research and workshop series »Where To?«, addressing the colonialist ideas of Theodor Herzl’s precursor Laurence Oliphant. »Where To?« is also the title of an exhibition arising from this long-term project and shown at the Digital Art Lab (DAL), as the Holon establishment is known. Unlike many renowned local art institutions, the DAL does not take the West as its lodestone in determining its approach: »We don’t look to New York, but to our neighbours – in Israel, Arab countries in the region or in South-east Europe«, says curator Udi Edelman. The project »Picasso in Palestine«, which brought a work by the painter to Ramallah for the first time in 2011 and exhibited it there, had its origins in this kind of fragile collaboration with regional partners.

Until April the word »Flight« was emblazoned upon the façade of the building. The closer you came to the letters, the clearer it became that they did not stem from a particular typeface but were instead composed from travel motifs laden with exotic-colonial associations. The interplay between the symbolic order of the text and the imaginary proliferation of the images, morphing into the shape of the letters, continued inside the building. Posters were available with images of the individual letters F, l, i, g, h, t. The work by Guy Saggee is entitled »Fight/Flight« and was part of the last group exhibition »Deviants«.

In this establishment, founded in 2001 as a platform for discourse and an exhibition space complete with video archive, the urge towards deviation could be interpreted in political terms too as a way of breaking with a mindset that might be described not merely as normal but also as normative. Sometimes simple interventions revealed the arbitrary nature of media settings – from the way in which the gaze is directed to the world through Internet searches right up to the function of testimonies in front of the camera. Amir Yazi turned his attention to the illusion-making machine of the US-film industry, which re-enacted D-Day and other war scenarios on Israel’s beaches in the 1980s. In a video, Roy Menachem demonstrated how the traumatic memories of a Holocaust survivor are disturbed over and over again by the banality of everyday life, for example by the arrival of a pizza delivery boy – or is this disturbance itself part of the documentary staging? In a video Lenka Clayton divides the famous speech by George Bush about the axis of evil into fragments and distils out of it a staccato of expressions that are often repeated a dozen times over, such as »freedom«, revealing an unconscious ideological underpinning beneath the swirling mists of rhetoric. »Comment« by Dor Guez, an Israeli with Christian-Arabic roots, shed light on the deep divisions in Israeli society, ignored by those convinced of Israel’s homogenous Jewish identity. Guez compiled the commentaries on an Israel-critical photo work about the ways in which the Palestinians have been dealt with historically, a work he exhibited in the Tel Aviv Museum in 2011. Alongside some approving comments, the documentation reveals the main audience reaction: »Go and join your friends in Gaza!«

Where To?, what might be dubbed the »Jewish question«, is also the question at the heart of the current eponymous exhibition. The show traces the contours of forgotten or marginalised alternatives to Zionism: »There were also non-national, non-territorial ideas that subscribed to the notion of the diaspora. We want to bring them back into the fold«, says curator Ram Kasmy-Ilan. There is a role in this context not just for obscure Jewish enclaves in the vicinity of the Niagara Falls, but also for a controversial long-term project by Yael Bartana on the fictitious »Jewish Renaissance Movement«, which has caused a great stir over the last few years. For Edelman, the new art star Bartana is obviously »part of the family«.

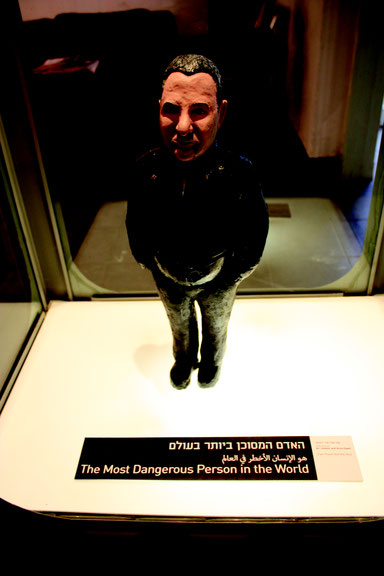

Another figure who is also part of the family is the prolific author, magazine publisher and curator Joshua Simon, recently appointed curator of the Bat Yam Museum. In September the exhibition he co-curated »ReCoCo – Life Under Representational Regimes«, which has already been shown at Vienna’s WUK, will be on display in DAL. Simon views this as an instrument »to combat the right-wing notion of what politics means. We are working on regaining politics in art. For there is depoliticisation in the realm of politics.« Until 19th. April, the group show »Iran«, which he co-conceived, and which was described in the liberal daily »Haaretz« as a clumsy, provocation-infatuated annoyance, was shown at the Spaceship Gallery. On the roof terrace a brightly painted rocket mock-up pointed up to the heavens, aimed just past the US embassy across the road, and out across the sea: its direction had to be slightly adjusted in response to pressure from the US authorities. Alongside readily decipherable »mockumentary« videos (for example on a planned Israeli attack on Auschwitz), which visitors could watch on mini plastic chairs designed for small children, the exhibition also included a wax statue of Defence Minister Ehud Barak, complete with the title »The most dangerous man in the world 2012«. This eye-catching gesture is mirrored in a work on Israel’s image, selling ironic souvenir T-shirts: »I went to the most hated place on earth (second to Iran) and all I got was this lousy t-shirt«, is the slogan. However, reality is often not far removed from this joke. On 17th May the BBC published the results of a study carried out all over the world, indicating that Israel ranked third in the list of countries with the most negative influence, behind Iran, which topped the league table.

Joshua Simon legitimates his exhibition concept in a statement as a self-confident sign of opposition to the sabre-rattling in Israel. In the interview he continues: »Iran plays a pre-scripted role in our political psychology. Before the Muslim Revolution, Iran, just like Turkey, was viewed as an ally. Later fears that Israel would become a kind of Iran took hold, as the Orthodox had gained ground within the country. In1995, after Yitzhak Rabin’s murder, there was a very popular rock song. It was called ›Good Morning Iran‹. Iran, and particularly Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has played the role of the enemy from within since then.«

There was a time when Roee Rosen, also represented in the »Iran« exhibition, was also viewed as the enemy within, breaking with taboos concerning what can be said and shown. His perplexing video »TSE«, awarded the 2010 Orizzonti Prize in Venice, presents masochistic pleasure in whipping as the basis for an exorcism of the body (of the people)(?), pushing out to the exterior covert forms of desire, derived from genuine racist quotations by Israeli Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman. In 1997 the artist, who had lived in New York for twelve years before this, showed his work »Live and Die as Eva Braun« for the first time at the Israeli Museum. The exhibition caused a scandal; the famous museum had to deal with demands from conservative and religious politicians to remove the installation. Rosen received death threats. The 66 drawings on paper in the installation were combined with a text that proclaimed life as Hitler’s mistress to be the ultimate entertainment experience, whilst at the same time shedding light on the abysmal cynicism of this point of view. Rosen updated this work in spring of this year with the title »Vile, Evil Veil«. Although in Israel popular culture in the form of the »Stalag« comics, which were extremely popular in the 1960s, had already »worked through« the trauma of the camps in a bizarre vein, as a lurid fantasy of sex and violence, the bounds of what can be depicted were apparently much more narrower in the fine arts. »Many critics consider ›Live and Die‹ from 1997 to constitute a paradigm shift concerning possible ways of representing the Holocaust.«

A retrospective of Rosen’s work was shown in 2012 at the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, but to date none of the major Israeli museums have any of his work in their collections. In spring the Israel Museum in Jerusalem bathed an overview of its most recent new acquisitions in the muted light of the »magic lantern« of the show’s title. Jerusalem-based art critic and publisher of the online magazine »Erev Rav« Jonathan Amir thinks that it is no coincidence that this type of melancholy-loving approach to contemporary art is so much in vogue: »The right-wing mainstream stance of depoliticisation is validated through references to the magical, divine and transcendental.« Amir is also harsh in his judgement of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. In June 2011 the long-serving director Mordechai Omer, described by long-serving museum curator Ellen Ginton as having an authoritarian leadership style and a conservative to reactionary view of art, left the museum. In the wake of discussions about the vacant post of director and the tent-city protests, the art scene regrouped and called for the museum to become more open »Israel is a banana republic«, Amir wrotes in »Haaretz« , commenting on the fact that the committee to select the new director was rapidly stuffed full of collectors, lawyers and sponsors. Artists were not represented, but called in noisy interventions for greater scope to have their say: at the same time a number of empty buildings in Tel Aviv were occupied by artists. Since then there has been some response to this call for greater participation; on the other hand however some from the art scene have criticise colleagues involved in these protests, accusing them of craving recognition and being obsessed with furthering their careers.

The new director has now been selected too. It is Suzanne Landau, former Head Art Curator at the Israel Museum, where the shows she curated included »The Magic Lantern«. Although her new colleague Ellen Ginton does sympathise with local artists, she gives short shrift to the idea of transforming the museum into a »house of artists«. Nonetheless the curator, a great fan of younger Israeli multi-media artists such as exiled Czech artist Jan Tichy or Ben Hagar, does expect things to take a turn for the better thanks to her new boss. Ginton’s current historic exhibition on the history of Israeli art is twined around the notion of identity, so controversial in this region, inspired by aspects ranging from the collectivism so widespread in the early years when the state of Israel was first being constructed, via the increasing fragmentation of Israeli society in terms of identity politics, and running right through to the purported contemporary state of »glocalism«.

However, artists with a Palestinian-Israeli identity like Dor Guez still remain the exception, whilst Jewish-Israeli stars like Sigalit Landau are represented both in the Tel Aviv Museum and in the »Iran« exhibition. Other Jewish artists have long been networked with Western centres such as London or New York, or, like documenta-13 participant Omer Fast, work in Berlin, the new hotspot for Israelis in exile. Contacts with their immediate neighbours in Arab countries in the region are conducted, conversely, through circuitous channels, Ginton explains: »Nobody would work with us. Either because the artists identify with the Palestinians’ struggle, or because their families would be threatened if they collaborated with us.« Before the museum’s doors were opened on that March evening for visitors in elegant evening dress heading to a classical concert, Ginton nevertheless sang the praises of her home town: »The marvellous thing about Tel Aviv is that, despite all this, it wants to be a fairly normal city in a crazy region.«

Translated by Helen Ferguson