For quite some time, my mind has been occupied with the question of what influence Facebook has on contemporary art. What would be the proper starting point to account for the dazzling movement of art circles on Facebook, the emerging relations, and the new modes of creating? Finally, Evgeny Morozov’s article in »The New York Times Sunday Review« on February 5, titled »The Death of the Cyberflâneur« pulled the trigger.

Morozov, author of »The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom«, compares the 19th century flaneur, who according to Balzac cherished ›the gastronomy of the eye‹, to the cyber–flaneur of 1990’s, who was the embodiment of a romantic wanderer as for instance can be seen in browser names (Internet Explorer, Netscape Navigator). The most curious point in his argument, however, is his critique of ›frictionless sharing‹ introduced by Facebook. Morozov starts off by arguing that individuality (the notion of romantic exploration) is increasingly vanishing, and we are being dragged into a universe where everything and everyone is starting to become anonymous.

[b]Writing Art History on Facebook[/b]

Then how does Facebook affect art, and the writing of art history as a new founding element? A first symptom is that today art history–whether this is acknowledged or not–seems to be moving towards the point where Vasari started off: collecting names and faces.

Artists are now also living on Facebook. They ›share‹ their latest works here, ›tag‹ themselves wherever they go, and they ›like‹ the things that impress them. Everyone is looking there now: the audience (any group of people who follow art) to figure out where to go, gallery owners (the market which gathers all collectors) to establish their own market, and artists to see what other artists are doing. Art works become visible here. Initiatives get organized there. A museum advertises itself on the same space. Books, essays, news articles are all being shared here.

Naturally, art historians have also started to turn their ›face‹ to Facebook. Just as Vasari gathered artists’ lives (Le Vite) to attach to the collections for the Medici, Facebook is now collecting the contents of artistic life for the contemporary market. In this space, which is designed by the institutional reason of social media, individual lives tend to dissolve into an anonymous atmosphere. As a form of meta–fiction, art history, which shares the same anonymous spirit (common sense), is today also being written on Facebook. It is not exclusively being written by scholars, theorists, or in the piles of catalogues by critics anymore, but in the elusive memory of the Internet. The flaneur used to draw parallels between time and passing clouds. Likewise, art history today seems to be over shadowed by a dissolving Facebook cloud.

[b]Spotting Commercial Art[/b]

Naming the pros and cons of this phenomenon is a difficult story. What interests me most is how to produce new criteria for contemporary art. How to establish standards for the writing of art history? Can Facebook act as a catalyst to spot commercial art?

This last question has become more of an issue when I saw Cai Guo–Qiang’s work »Head On« in his exhibition titled »I Want to Believe« held in 2009 at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao/Spain.

The work is an installation presenting 99 wolf replicas running head on into a glass wall. This visually impressive work urges the viewer to look twice inquiring into its reality. The work has a dramatic ring to it, in that this pack of wild animals struggle in vain trying to break through a glass wall that stands within the white walls of the museum. There is a correlation between the power of leaping wolves and their subsequent pain. This scene which is re–animated in a sterilized exhibition hall forces the audience to experience an intimate moment. It must be a feeling like that, which pushes the Internet user to like and share the photo of a work of art. It is a visual correlation that the viewer is forced to establish. It is a drama produced by reality that replaces abstraction. That is to say, it is comparable to the portrait of a weeping child hung on the wall with a teardrop on his cheek.

Let us suppose that the user takes a step further and checks what has been said and written about this work. The Internet user will come face to face with the fact that the work of the Chinese artist refers to a series of macro issues such as nature–culture dichotomy, environmental issues, the Berlin Wall and above all, he/she will learn that the work belongs to the Deutsche Bank Collection; and that the artist has a political stance associated with the Maoist tradition. Then the Internet user is probably astounded, his/her mind is in some kind of disorder; and he/she turns back to the photo. Where exactly is the dramatic texture of the work, which was still there a short time ago? How could the work change its identity so fast? How could so much engagement occupy the world in front of him/her just as he/she was about to download the photo and use it as the screen background? Naturally, the spectator starts questioning whether those qualities lurk in the work he/she sees, or whether they have been put there by a malicious army of critics.

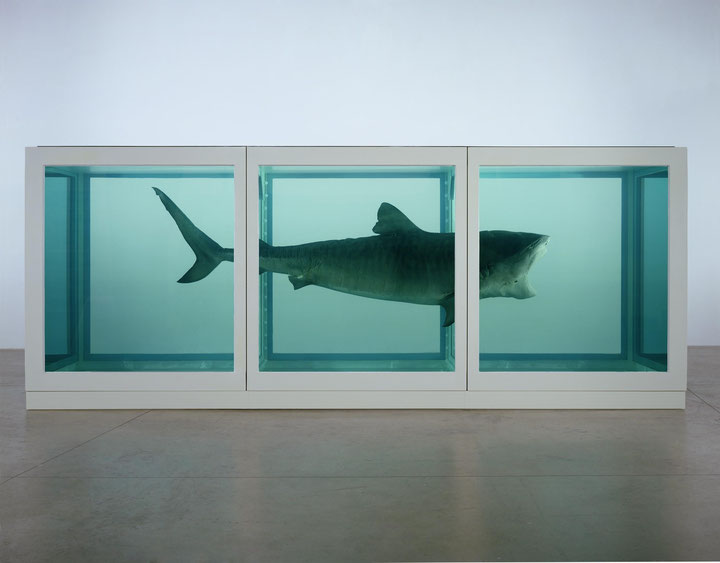

Such speculative reasoning may require a specific case, in which a work or the perception it evokes is analyzed. In that respect, a comparison with Damien Hirst’s »The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living« might be fruitful. Both works abuse the sense of reality; but while Hirst’s conceptual installation is entirely based on conceptual means, Cai Guo–Qiang’s work relies on the power of visuality and the ease of assigning an outer concept (visual means) to the work. Such a comparison might also reveal why images of Hirst’s work are not shared on Facebook as much as images of the other.

To put it in a nutshell, although the rate of likes and shares on Facebook does not provide satisfactory first–hand data to assess the quality of a contemporary work of art, it gives an idea about the social reflection that the work corresponds to in reality. Considering Zygmunt Bauman’s thesis that »the art that the flâneur masters is that of seeing without being caught looking«, producing a work of art today is harder than ever as the artist is overwhelmed while at the same time floating on the waves of visibility on Facebook. Today’s Internet user does not ›surf‹ anymore. Instead, he/she uploads himself/herself to the net while seated. Still, he/she is the strongest criterion as a receiver of art.