Inasmuch as it offers a radically new perspective on the relation between the artwork and the viewer, the thinking behind speculative realism and object–oriented philosophies is proving increasingly attractive to artists and curators, who are aligning themselves with it to different degrees. In the first of the following three interviews, curator and writer Tom Trevatt discusses the aims of The Matter of Contradiction, a four–part project and conference series he is currently co–organizing that explores the prolific connections between art and these philosophies. Emphasizing the necessity of renouncing the fantasy of human dominance over objects, the project conceives of an art drawing on ecological thinking – which considers the human species as one object among many, in a world indifferent to it. In the second interview, curator Vincent Normand gives an eloquent example of how these seemingly abstract ideas can be applied in art and exhibition–making: his exhibition Sinking Islands constitutes a presentation of objects that are not defined by their relationship to the viewer – and are therefore staunchly indifferent to her or him. Their profoundly disturbing implications for art notwithstanding, these notions of ecology and of the de–centred human subject are by no means confined to a circle of initiates but are also resonating further afield. In the third and last interview, Ami Clarke, artist and director of the London art space Banner Repeater, elaborates on her engagement with critical art, and the concerns she shares with the afore–mentioned philosophies and practices.

[b]Rahma Khazam:[/b] You recently co–organized a conference titled Ungrounding the Object (September 2012, Vassivière, France) on the theme of the object as conceived outside of human access. What were the main issues the event addressed ?

[b]Tom Trevatt:[/b] I am part of a team engaged in an ongoing investigation of the possible conditions for thought about art as it exists within current geo–philosophy. This team consists of Sam Basu, an artist and co–director of Treignac Projet, Fabien Giraud, a French artist and Ida Soulard, a French art historian, who together run inkhuk, a residency and studio in the Limousin, France. Our ongoing project, The Matter of Contradiction, began in 2011 with a talk and discussion with philosopher Quentin Meillassoux at the Paris art space Rosascape on the occasion of Fabien's exhibition. Ungrounding the Object, a week long workshop in Treignac Projet and two day conference held at Vassiviere, is its latest installment. Our project attempts to think art through an ecology of objects determined not by human separation and dominance over objects, but through an entangled mesh. The human is entangled within an ecology of objects, as one object amongst others, rather than as a prioritised and prioritising subject. To account for the recent ecological crisis the anthropocentrism of much of our inherited continental thought must be abandoned in favour of a flattening of the ontological field. Contrary to any nostalgic safeguard of nature’s supposed essence, the thought of ecology allows us to think beyond the human, offering a speculative opportunity to rethink realism.

[b]Khazam:[/b] The Ungrounding the Object conference was preceded by a preparatory workshop that examined the evolution of art under the condition of the anthropocene. Could you explain what you mean by the anthropocene and how it affects art–making ?

[b]Trevatt:[/b] The anthropocene is the geologic chronological term used to indicate the extent of human activity on the globe, producing a new geological era. The implications of this are important. No longer can we see ourselves as independent from and in contradistinction to the earth we rest on, instead we are implicated in the procedures and activities that affect its very geological reality. This, as we describe it, produces a shock that determines our engagement with the real. Art, if it is to propose a realism, must abandon the fantasy of human dominance over the object, or culture over nature. Instead it will have to progress via a logic of entanglement whereby it must understand the human as necessarily a part of a world radically indifferent to it.

[b]Khazam:[/b] The workshop set out to identify the risks to which art is exposed when it attempts to address the notion of the anthropocene. Could you talk about these risks and how they might be avoided ?

[b]Trevatt:[/b] Yes, we identified a number of possible risks or dead ends. For example, art might respond to the thought of the anthropocene via a presentation of the object. A lot of contemporary object based art uses the recent philosophical movement of Object Oriented Ontology as a guise under which to smuggle in an art of materiality as an illustration of the philosophy. However, we suggest that this is a reinstatement of the sublime that brings back the relation between the viewer and the artwork through a representation of the real within the gallery. Another example of a dead end is the didactic response, which would be to produce an art that tells you how to think about the anthropocene. The entanglement of thought with the anthropocene requires a problematization of the relation between the art object and the viewer subject that draws on an ecological understanding of reality rather than reinstating the dominant human subject.

[b]Khazam:[/b] Ungrounding the Object comprised talks by philosophers such as Graham Harman and Levi Bryant. As a curator, how does your practice intersect with their writings?

[b]Trevatt:[/b] A lot of my recent work has embarked from positions that I develop in my thinking in relation to these and other thinkers. I would say that the ideas of Harman or Bryant are important stepping stones in the production of a curatorial practice that attempts to think the real.

[b]Khazam:[/b] Do you regard anti–humanism as an emancipatory project that may help to resolve the current tensions in contemporary art and society ?

[b]Trevatt:[/b] I am dissatisfied with the operations that contemporary art performs, but post or anti–humanism cannot be dialectically opposed to humanism as a way to escape the problem. Emancipation is likewise completely the wrong approach to these issues: what strikes me as important is to produce a greater understanding of the entangled reality, not to attempt to extradite yourself from the situation. This just repeats the dialectical gesture of human versus object critique that we oppose in our work.

[b]Khazam:[/b] Could you talk about the exhibition you recently curated at Banner Repeater and how it relates to the issues covered at the conference ?

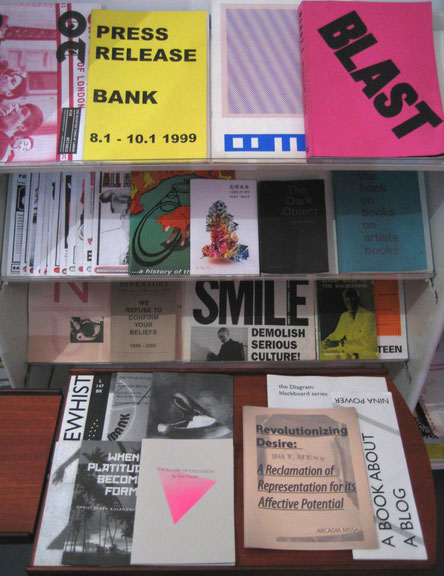

[b]Trevatt:[/b] I am working with the artist Christopher Kulendran Thomas on, among many other things, his ongoing endeavour, When Platitudes Become Form. This iteration of the work at Banner Repeater is one among many versions of the same piece. The work is, briefly, the purchase of artworks realized by some of Sri Lanka's best–known contemporary artists from galleries in Colombo, and the reconfiguration of these works by Kulendran Thomas for the London contemporary art market. The sale of these works in the West provides money for the production of a covert film–making platform that will resist the oppression of communities displaced by the Sri Lankan civil war. When Platitudes Become Form thereby highlights the aesthetic and financial differences between London and Colombo, between the centres of art power, and its margins, while producing invisible political affects that elude the interpretation of the artwork by the viewer. The publication that we have produced in connection with the exhibition includes an essay I have written covering many of the issues I have discussed here. Kulendran Thomas's work has been an incredibly useful way to think an art that can reflect in interesting ways the theoretical ground that the ongoing conference project has been engaging with.

The Matter of Contradiction will hold its third event at DRAF, London from 1–3 March 2013 http://lamatiere.tumblr.com/

Tom Trevatt's publication The Allure of Collusion is available at http://www.bannerrepeater.org/

_________________

[b]Rahma Khazam:[/b] Last summer you curated an exhibition titled Sinking Islands (LABOR, Mexico City, July 14 -– August 31 2012) in which you addressed the question: „What would be an exhibition of things flat–out alone, requiring the presence of no one? “ 1 How do you view the relationship between the artwork and the viewer?

[b]Vincent Normand:[/b] The idea behind the Sinking Islands project – which unfolded both as an exhibition and as a publication – was not so much to put on a show without spectators as to present objects that were defined neither by their relationship to the viewer, nor by categories of discourse and language. So the project was not about rejecting the spectator's subjectivity but about objects resisting their dissolution into the relational field – and instead becoming things ‚alone’, divorced from human language and discourse.

My starting–point was the idea that any exhibition proceeds from the construction of an insulating layer that allows it to exist and make sense for us. Sinking Islands was an attempt to think how this insulating layer could be eroded, as when the foundations of an island are eroded and it sinks into the sea.

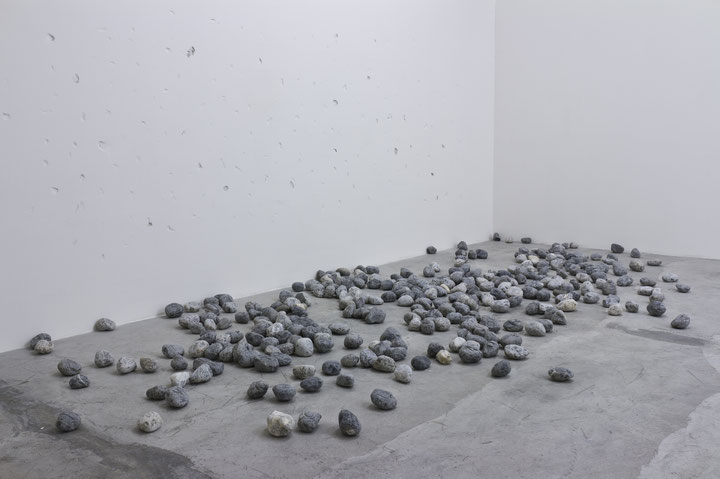

[b]Khazam:[/b] The works in the exhibition included Etienne Chambaud's Lapidation Piece (2012), 350 inscribed stones lying on the ground after having been thrown against the gallery wall, and Nicholas Mangan's A World Undone (2012), a video in which fragments of the mineral zircon are seen falling in slow motion through the air. How did these pieces fit into the theme of the exhibition ?

[b]Normand:[/b] The objects I gathered together were material manifestations of simple gestures – cuts, stitches, falls, inserts, meshing, sedimentations. However the abstract space of aggregation and transmission where the authority of the curator is supposed to happen, the paratext we expect him or her to build between and above the objects to make them explicit, was not providing sources and referents, as is usually the case. If the exhibition is a device by which the spectator is mobilized to redeem the objects from their muteness in order to make them available to language and epistemic appraisal, then Sinking Islands can be said to have done the reverse, by pointing up its irreducibility to any rescue by the spectator.

[b]Khazam:[/b] Do you consider Sinking Islands as an emancipatory project that can help to resolve the tensions in contemporary art and society ?

[b]Normand:[/b] I consider this exhibition but also my curatorial practice in general as an attempt to slice through the avalanche of things that characterizes our contemporary condition. As the French philosopher Tristan Garcia recently pointed out, we are witnessing an ‚epidemic’ of things, of overlapping factors, networks and events that obstruct knowledge and that thought cannot follow. This condition is an epistemological ‚panic’, in which everything is ‚something’ and there seems to be no such thing as a negative operation. Under these circumstances, any declaration of exception, withdrawal or difference becomes just another contribution to the mass of things. What I call irreducibility is a possible response to this process of ongoing accumulation.

Sinking Islands, a publication edited and printed on the occasion of the exhibition Sinking Islands (LABOR, Mexico City, July14 –August 31 2012) is available on–line at http://www.scribd.com/doc/100686320/Sinking–Islands–BOOK

________________

[b]Rahma Khazam:[/b] You run Banner Repeater, an art space and artist publishing platform dedicated to developing critical art. How do you define critical art and why did you choose to open an art space in a working train station ?

[b]Ami Clarke:[/b] Banner Repeater takes advantage of the natural interstice provided by a working train station environment with high numbers of passing public, enmeshed in a broad ecology of networks, to site experimental art works in a highly visible artist led project space and reading room dedicated to artists publishing. The dissemination of free pamphlets and other publications with a focus on critical and experimental writing, at 8am in the morning to a packed platform of commuters, serves to distribute this often challenging material to a broad and indiscriminate audience.

‚Critical art’ is a thorny subject, as much of it is caught in a deadly end–game, performing a parody of itself that limits any kind of radical thinking. I'm interested in awkward experimental work that challenges current thinking, boldly aware of the contingent frameworks in which it operates, and that potentially has an effect on our everyday lives.

[b]Khazam:[/b] Are you sympathetic to speculative realism and object–oriented philosophies ?

[b]Clarke:[/b] The current work in the project space, Christopher Kulendran Thomas's When Platitudes Become Form, curated by Tom Trevatt, (author of the new Banner Repeater publication The Allure of Collusion), attempts to analyze how art work might take into account the whole ecology of art, in relation to, whilst also being critical of, some of the more interesting ideas that come out of Speculative Realism and Object Oriented Ontology.

Banner Repeater also operates within a network of relations and art/market forces, with their own self–preserving value production, but focused on experimental art production that is disseminated in the general population/mainstream and that goes some way towards challenging established ideas of the production and reception of artists' works. What might be key here is my emphasis on Banner Repeater being an artist led space, and the way in which I approach it as an art project – not as an art work as such, but the lines are certainly blurred. It too perhaps exceeds the limited horizons of the relation between art ‚work’ and viewer.

http://www.bannerrepeater.org/

1 Vincent Normand, The Sunken World and the Desire for the Shore, from the publication Sinking Islands, LABOR, Mexico City, 2012